News & Updates Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Books Tell You Why, Inc.

From the ILAB Archive: Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Famous Literary Hoaxes (Part Two)

For particular content and further reading, "search for articles" HERE!

Enjoy the read!

By Joachim Koch

11 March 2013

Back in 400 BCE, Dionysus the Renegade was a Stoic philosopher and student of Zeno of Citium. He wanted to humiliate his rival Heraclides and decided to forge a work of Sophocles. Dionysus inserted the acrostic "Heraclides is ignorant of letters," which quickly led to the discovery of Dionysus' fraud - but not before he'd achieved his aim of embarrassing Heraclides. Since then, the literary hoax has played a fascinating and engaging role in history. In Part One, we focused on the Ossian poems, The English Mercurie, and Thomas Chatterton's Rowley poems. Now, delve into William Ireland's spurious Shakespeare, Davy Crockett's attempts to combat false autobiographies, and more.

Sham Shakespeare

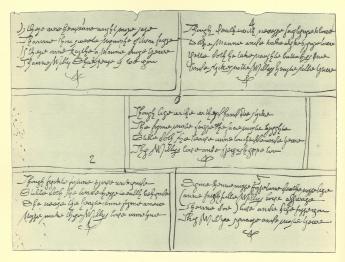

In 1794, William Henry Ireland, the son of British engraver and Shakespeare aficionado Samuel Ireland, made a miraculous discovery. Young William presented his father with a mortgage deed, signed by none other than Shakespeare. He hinted that he'd found it in a friend's collection, and that there were more documents to come. Ireland the elder was predictably delighted. William soon brought a steady supply of the Bard's documents, from receipts and correspondence, to a letter from Queen Elizabeth I extolling Shakespeare's virtues and a love poem to Shakespeare's wife, Anne Hathaway. He eventually produced two undiscovered plays, "Henry II" and "Vortigern and Rowena."

Soon the Irelands were quite famous, but the positive sentiment didn't last long. The handwriting on their documents didn't match known samples of Shakespeare's writing. Then "Vortigern and Rowena" was performed on stage, and it was clearly impossible that Shakespeare had written that disaster of a play. In March 1796, a leading Shakespeare scholar denounced the Ireland documents as phonies, and William confessed to having forged them. He said that he'd only wanted to please his cold and distant father.

Remember the Alamo

US Congressman Davy Crockett made his name as a folk hero before entering government, and he used that reputation to his advantage. But these myths soon grew out of control - some of these threatened to ruin his career, while others resulted in profits for the unscrupulously enterprising. One such example was a spurious autobiography entitled Life and Adventures of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee, published by James French in 1833. Incensed, Crockett undertook to set the record straight, and by February 1834, he was putting the finishing touches on his real autobiography. He writes in the opening pages, "A publication has been made to the world, which has done me much injustice, and the catchpenny errors it contains have already been too long sanctioned by my silence."

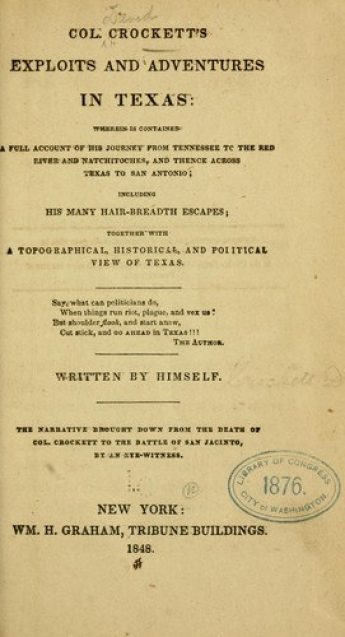

But soon after Crockett died at in March 1836, another autobiography surfaced. Col. Crockett's Exploits and Adventures in Texas, written by himself was supposedly taken directly from Crockett's own journal. It included sensational accounts of Crockett's adventures and even his last stand at the Alamo. Crockett's status as a legendary hero propelled the autobiography's popularity. It wasn't until 1884 that the autobiography was revealed to be a hoax. Richard Penn Smith, a newspaper editor, lawyer, and minor playwright had dashed off the fake autobiography in less than 24 hours, using a selection of historical and fictitious sources. Works about Davy Crockett like those by French and Smith have proven a considerable obstacle in stripping away the myths surrounding this legendary character.

A Secret Plot with Disastrous Results

Political strife ran high in Russia at the turn of the twentieth century, and the Russian secret police often resorted to extreme measures to accomplish their objectives. They published Protocols of the Elders of Zion, supposedly the top-secret records of a meeting of Zionist leaders in Basel, Switzerland in 1897. According to these so-called records, the group conspired to execute a socialist Jewish-led takeover of the financial, cultural, and governmental centers of power. Protocols took the form of 24 chapters, which were really cobbled together from a variety of Jewish and anti-Semitic sources, and even a French satire of Napoleon II.

Soon Protocols was used as the basis for violent anti-Semitic programs in Bolshevik Russia. Communist leaders also used the work for their own ends. In America, Protocols was used to illustrate the connection between Jews and the "Red" menace. It was published in newspapers across the country, including the Dearborn Independent, which was owned by Henry Ford. Ford published a number of anti-Semitic works and paid to have 500,000 copies of Protocols printed. He was only stopped by court order. By that time, the document's true origins were already well documented, but that didn't quell interest. Adolf Hitler quoted Protocols in Mein Kampf, and made it mandatory reading for Nazi schoolchildren. Although considerable efforts have been made to eradicate the document, it remains in print in several parts of the world.

A Brazen Autobiography Attempt

Clifford Irving approached McGraw-Hill in 1971 with an odd and tempting pitch. He said that he had been hired by the elusive airline mogul Howard Hughes to co-author Hughes' autobiography. By that time Hughes had been virtually invisible for almost a decade, so publishing his autobiography was sure to be a huge money maker. Irving claimed that Hughes had originally contacted him about ghostwriting an autobiography, producing correspondence and "interviews" to validate his account. Irving's accomplice had forged the documents after scrutinizing Hughes' handwriting.

As McGraw-Hill began to leak hints about the upcoming book, Hughes' associates grew suspicious; the move seemed completely uncharacteristic of the eccentric recluse. Then in January 1972, Hughes agreed to a telephone interview. He spoke out against Irving and made it clear that the two had never even spoken before. Irving, his wife, and his accomplice were all convicted of fraud. Irving spent over a year in prison. He went on to write his own account of the Hughes debacle, which was adapted for a 2006 movie starring Richard Gere called "The Hoax."

(Posted on Books Tell You Why, presented here by permission of the author.)