Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Simon Beattie Ltd

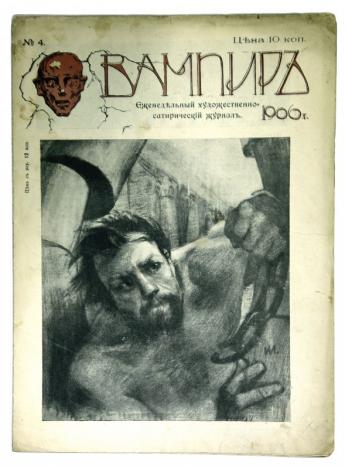

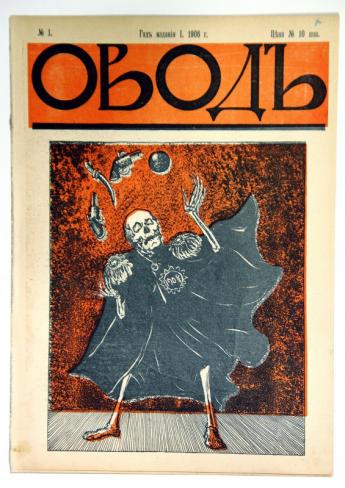

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Blood and Laughter

By Simon Beattie

The boom years of 1890s Russia came to an abrupt halt at the turn of the century when an economic slump left many of the new urban working class jobless and led to unrest in the countryside. The Tsar’s popularity took another knock when hopes of a quick military victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904) were quashed by a series of disasters and humiliations on land and at sea. Strikes at home ensued.

On 9 January 1905, 150,000 striking Petersburgers and their families converged outside the Winter Palace to hand a petition to the Tsar, demanding basic civil rights and labour laws. But the peaceful demonstration, led by Father Gapon, was broken up by live rounds from the Imperial Guards; as many as 1000 people were killed, and several thousand others injured. The 1905 Revolution - in Lenin’s words, ‘the dress rehearsal for the October Revolution’ - had begun.

‘Bloody Sunday [as 9 January came to be known] killed superstition, the old faith in a just Tsar, and unleashed a tumultuous rage among the masses … A huge wave of strikes swept the country, paralysing more than 100 towns and drawing in a million men and women. Throughout the summer peasants rioted while terrorists struck at figures of authority.

‘Alongside the struggle in the street and factory was the struggle for the free press. Ministers and clerics suffered assassination more by the pen than the bullet as the revolution strove for the expression of powerful emotions long suppressed. A flood of satirical journals poured from the presses, honouring the dead and vilifying the mighty. Drawings of frenzied immediacy and extraordinary technical virtuosity were combined with prose and verse written in a popular underground language …

‘For a few brief months the journals spoke with the great and unprecedented rage that neither arrest not exile could silence. At first their approach was oblique, their allusions veiled, and they fell victim to the censor’s pencil. But people had suffered censorship for too long. Satirists constantly expanded their targets of attack, demolishing one obstacle after another as they went, thriving on censorship. The workers’ movement grew in boldness, culminating in the birth of the St Petersburg Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, the people’s government. For fifty days the Tsar and his ministers were confronted by another power, another law. Journalists and printers seized the right to publish without submitting to the censor. The satirical journals then reached their apotheosis, until the revolution died as it had risen, bathed in blood. More clearly than any party resolution or government proclamation, the caricatures of 1905 tell the story of that heroic failure …’

(Cathy Porter, Introduction to Blood and Laughter: Caricatures from the 1905 Revolution, London, Jonathan Cape, 1983, pp. 18–9).

(Published on Simon Beattie's blog "The Books You Never Knew You Wanted", presented here by permission of the author.)