Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Adrian Harrington Rare Books

We All Have Issues

By Bibliodeviant

“Dear Bibliodeviant,

I miss you terribly. I long for those sultry evenings we spent in your simple, rustic lakeside retreat sipping Chateau Mouton-Rothschild and eating sweetmeats. Most of all I miss curling up on your ethically sourced Kilim rug in front of a roaring log fire while you told me those gloriously witty stories about how the printers misspelled “Wade” for “Wabe” in the first edition of Through The Looking Glass, or how bookdealers in the past have charged high prices for copies of the Time Machine that didn’t have Hall Caine’s The Manxman on the first page of advertisments. I yearn for you, and your thrilling tales of the swashbuckling world of the rare book trade. Return to me immediately, and talk to me of fine bindings! Monica”

Now, it’s a well known fact that all rare book-dealers receive letters like this. Ben of Peter Harrington Rare Books for example, receives up to three feverishly written letters a day from such avid admirers as Una Stubbs, Ashley Cole and the man dressed as Nelson from the Admiral car insurance ads. In fairness, this is not merely because of his book knowledge, but also because they think he’s yummy.

However it has to be said, in reference to the letter above that young Miss Bellucci raises an interesting point. Not about me obviously, more about the nature of issue points. What does a bookdealer mean when he or she says “First Edition, First Issue.”? Is it important from a collecting standpoint? Are the stars just pinholes in the curtain of night? Who knows?

The estimable chaps at biblio.com have this to say about issue points:

“Points are physical attributes that are specific to a printing or edition of a book, such as a typo on a specific page that was corrected in later printings of a book. An issue of a book is a specific change in the book during the printing of an edition. A first edition of a book may sometimes have two or more issues, which would be defined by a change or correction in the text, binding style, or any other physical feature of the book during the first edition printing. Typically, the first issue of a first printing would be the most desirable copy for a book collector.”

John Carter (kind of the Yoda of the rare book world) has this to say from his ABC for Book Collectors:

“When alterations, corrections, additions or excisions are effected in a book during the process of manufacture, so that copies exhibiting variations go on sale on publication day indiscriminately, these variant copies are conveniently classified as belonging to different states of the edition…When similar variations can be clearly shown to have originated in some action taken after the book was published, two or more issues are distinguishable.”

It should also be noted that immediately after writing that definition John Carter was head-hunted by the DHARMA Corporation for work in their Orientation Film Dept. His last known whereabouts was somewhere in the Southern Pacific, muttering something about the Casimir Effect.

We’ll use the Bloomsbury first trade edition of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban as a simple, straightforward example of an issue point (and one that actually impacts the value of the book, not all do).

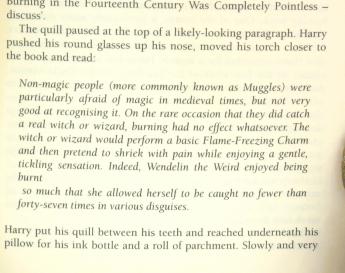

The first page of text (page 7 for those of you grabbing your copy off the shelf) has an italicised paragraph towards the bottom of the page, part of a text-book Harry is dipping into:

You’ll notice that after the word “burnt” five lines up there’s a dropped line where “so much…” should carry on but doesn’t. This dropped text line is the issue point. After printing a number of copies of the first printing they noticed the error and corrected it. The ones with the dropped text went to bookshops along with the corrected ones and were sold. There are far fewer of them, and they technically pre-date the other, corrected copies so the defect makes them more desirable. The difference in price at one point was ten times that of a standard corrected (second issue) copy.

That’s an issue point. This book would probably end up catalogued as first edition first issue (although for some reason with Harry Potter you need to throw in “first impression or printing”, no idea why, before Harry Potter books I had probably not been asked if a book was first printing: I’ve catalogued it as a first edition, what the hell else would it be? Grumble).

It should be added that the definition is pretty much in the name, a book with an issue point needs to have been ” issued” by the publisher, it has to have actually have been out in the world with significant, noticeable differences from its fellows.

The issue points in question can be many things: corrected mistakes as above, altered images (Martin Chuzzlewit has a corrected “£” on the illustrated title page. Huckleberry Finn has a doctored engraving to remove what looked like an inappropriate erection from the image of Uncle Silas…really), and the removal of scenes, characters and chunks of text after publication as a result of legal action (Robert Graves “Goodbye To All That” and Waugh’s “Scoop” spring to mind), or to avoid the possibility of being shot by Lord Byron (Polidori’s The Vampyre).

The above are all genuine issue points. It gets far more shaky when you start factoring in advertisements, dust-wrappers and all the accumulated hearsay of a trade that thrives on gossip and an arcane belief that the more you behave like a misunderstood Victorian caricature the better book-dealer you are.

I personally don’t like advertisement points (mostly). They occur when you get a first edition of a book, say Conrad’s Youth or Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone and decide that a certain dated advertisement insert denotes an earlier issue of the book. Sometimes the homework has been done, the research painstakingly completed and you can say without a shadow of a doubt “March 1851 ads went into the earliest copies of this book”. These occasions are in truth fairly few and far between.

Ads booklets or inserts are a) produced separately from the book b) really have nothing to do with its status as a first edition of the work in question and c) are inserted in what were usually fairly uncomfortable conditions by a couple of underpaid blokes who most likely couldn’t read.

They are however widely accepted as a method of deciding precedence (and often price). Weirdly enough, for a long time the ads dated closest to the date of publication were accepted as denoting the earliest issue of that book. After accidentally witnessing some real life business practises however bookdealers realised that when you are putting ads into your book you probably want to advertise the unsold stock filling up your warehouse rather than the stuff you haven’t actually printed yet. If a book is printed in June, ads dated April the same year would be more likely to be early inserts than ads dated July.

Dustwrapper points (although nowhere near as random) are also a little bit annoying as the dustwrapper is again produced elsewhere, often by different printers, mated with the book at a later date, withdrawn, overprinted, priceclipped by the publisher etc. Unless there is a definite train of evidence showing that 1000 wrappers were overprinted with a favourable review on such and such a date then it comes down to guesswork, experience of the book and knowledge of the industry (which is why you should go to a bookdealer who has been around a while and is a member of a reputable trade organisation). Naturally the further back you go the less chance you have of finding cast-iron evidence for something and you have to scrabble around looking for any detail you can find.

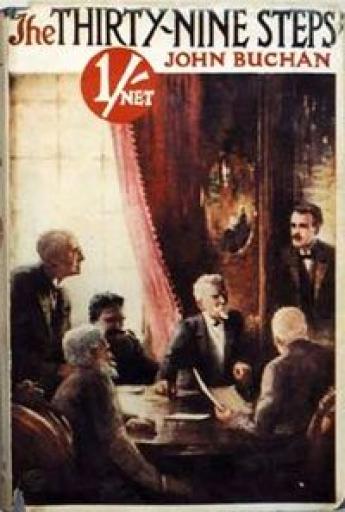

The legendarily scarce wrapper for John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps (Blackwood’s 1915) is a case in point. There aren’t very many knocking around, and there’s been a bit of scuffling about what actually constitutes the earliest issue of the wrapper for quite a while, there simply have been enough copies recorded or seen to be able to say “That is the one, no shadow of a doubt.”

My personal theory (which loads of clever people don’t agree with) is that tons of copies went off to war (Buchan was a firm favourite of your chap in khaki). If you look at the dustwrapper of The Power House (same publisher, same format, same author, published a very short while later) the flaps of the dustwrapper are actually a removable order form for more Blackwoods products. I don’t see any reason why the earlier Thirty-Nine Steps wrappers shouldn’t have had the same feature. I reckon people cut them off, filled them out (much postage was free to armed services personnel on active duty) and used the remaining bits as toilet paper or kindling. A mechanical reason for there not being more examples available is always the best one, without even one flap a dustwrapper won’t stay put.

To be continued…