Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Ten Pound Island Book Company

The Art of Book Cataloguing - British Bottoms

By Greg Gibson

The differences between paper and digital catalogs are obvious, but some of the results of those differences continue to surprise me. For example, in the old days orders from my paper catalogs would dribble in over a period of weeks. I used to mail them all first class, in three staggered mailings, hoping to achieve some kind of evenness in delivery, but customers were always complaining that their catalogs arrived late, and demanding exclusive previews. Others, more laid back, would wait for moments of leisure to read their catalogs, and some overworked acquisitions librarians required days or weeks to claw through the pile of incoming mail to discover where my list of treasures was buried. Digital catalogs, on the other hand, play out in an eyeblink. Everyone gets their catalog announcement via a Mail Chimp email blast within the same hour or so. Those who are highly motivated know that they must read it and respond immediately. Consequently, most of the orders arrive by email within the first few hours of the catalog’s life. Maritime List 238 was posted Sunday night. By Wednesday even the laid back orders had arrived.

In my idiosyncratic way of doing things I give each catalog a name. (In the old days catalogs were assigned random names, probably to insure accuracy when ordering by wire. Some book dealers, like my friend Anthony Simmonds in the UK, continue this practice. Two of his recent catalogs were called “Byron” and “Madrid” – Why? Who knows. It all sounds excitingly hush hush, like some WW II cypher.)

Anyway, my catalog names suggest themes for each catalog. Maritime List 238 was called “Just Like Old Times.” The joke was that in the old days booksellers sold books rather than ephemera, documents, manuscripts, etc., and this catalog contained nothing but books. The joke went over pretty well. Maritime List 238 sold just about 50%.

There was another catalog’s worth of material sitting on my shelves and, since I’d already extracted all the books, this lot contained nothing but the aforementioned ephemera, documents, manuscripts, etc.

Because all this ephemeral and manuscript material pertained to nautical matters, I’d already decided to call the catalog “Wet Paper,” The joke being that… I don’t really have to explain it, do I?

The lovely thing about cataloging books is that you can look them up on the Internet and steal other people’s descriptions (which, of course, you fact check and put into your own words). Or if you’ve cataloged the book previously you can cut and paste your old description, with appropriate alterations for condition and edition and so forth. In other words, compared to manuscripts, books are a snap. Manuscripts, by their very nature, tend to be unique, each written by a particular person at a particular time and place for a particular reason. You have to read the darned things in order to catalog them …. I don’t really have to explain it, do I?

So, yesterday morning, with a mildly disgruntled sigh, I pulled the first manuscript off the pile. Judging by the opening index, it was an account book of some kind – no, not an account book. A letter book. Written from Manchester wherever to people in Boston and other un-named locations, by a guy called “yr obt. svt.” or, “yrs respectfully” or similar unenlightening handles. And what was he writing about? Money. He seemed to be trying to get someone in Boston to pay someone else with money the Boston guy owed him, like a second party check. And right there in the third letter he referred to “the embarrass’d situation of our commercial concerns.”

What was going on?

Well, let’s see. By 1811, the dates of these letters, Manchester, NH had gotten started as a mill town, but it hoped to become the “Manchester of America” referring, of course, to Manchester, England, where they made a lot of textiles which, according to his letters, Yr Obt Svt. was busy trying to sell. But there were problems. Chief among them was the fact that, while he was trying to conduct business between Manchester England and Boston Mass., Britain and America were about to go to war. What Yr Obt. Svt. was really concerned with was the constriction of the flow of capital and goods. Political circumstances opened a small window of opportunity for him, and he was trying his damnedest to push as much business as he could through that small opening.

Suddenly I was reading these letters with different eyes. This was world history at a granular level – a record of the effects of the War of 1812 on an American merchant. What began as a slog through some wet paper became a fascinating couple of hours.

Terrific, huh? Well, when I went back to work Monday morning, I took the next book of the pile with a sort of disgruntled sigh and, lo & behold, it was a companion volume to the letter book! A complete accounting of all the stuff he’d shipped to Boston in 1810-1811, and now was trying to get paid for. Made my day.

Here’s how I described them…

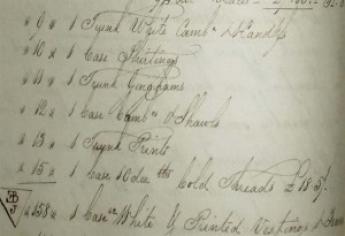

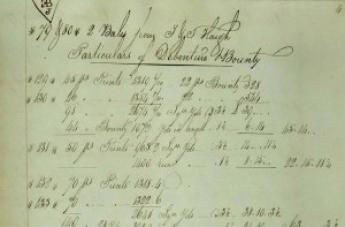

Textile Merchant’s Letter Book, Manchester England – Boston, Mass., January 1811- March 1812. (with) Account of Shipments Corresponding to Letters. Manchester, England. 1810 -1811.

Three folio volumes, 70, 71, and 24 pages of manuscript. A fascinating series of letters from a textile broker doing business in Manchester, England, to correspondents in Boston and England, as he scrambles to solicit and complete shipments of orders placed by Americans prior to Gallatin’s alteration of the Non-Importation Act. In one letter he writes, “I learn that Mr. Gallatin recommends such reversal of the Non Importation Law to take place on the 2nd Feby. as that all goods purchas’d or order’d in this Country may be admitted to an entry, consequently the ships are now taking in freight very rapidly.” To another correspondent, “Mr. Gallatin’s report with a recommendation to Congress to revise the Non-Importation Law… is what we had reason to expect from a government which is not YET completely mad.” He also mentions Pinckney departing the country on the “Essex Frigate” and later writes, “Owing to the vigorous measures of Bonaparte to annoy the commerce of this country & the dispute with America the embarrassment of the Manufacturers & Merchants are very great…the departure of Mr. Pinckney will arrest, for the present, all negotiations on this side of the Atlantic.” In April he writes, “accounts have been receiv’d here… giving the final proceedings of Congress from which it appears all commercial connexions with this country have ceas’d… it is reported that this government will shortly issue a decree prohibiting the importation of American produce except in British Bottoms.” Subsequently, he also has to deal with the fact that American vessels arriving in France after the alteration of the Act were sequestered – an order that the French reversed in April 1811. These political variables, of course, affected the flow of goods and money, and the delays occasioned further expenses that had to be accounted for. (His letter of 17 Jan 1811 itemizes Particulars of Debenture & Bounty.) So, in addition to documenting an important moment in international politics, the main content of these letters reveals the effects of the global situation on a single merchant. He returns to Boston in August 1811 and sets about collecting debts, an activity that meets with little success. In October he describes himself as “being in haste & having little to communicate on business it being in a state of stagnation.” The last letter is written from Boston in March, 1812, just months before the beginning of hostilities. “I have now concluded to sail as soon as restrictions on trade are remov’d” As it turned out, he’d have years to wait… And I thought the book business was difficult! This is accompanied by a 70 page book book of invoices itemizing goods shipped aboard named vessels from England to Boston in 1811 (which shipments correspond to those mentioned in the letters), and by a second 24 page book of invoices, itemizing goods shipped from Manchester in 1814. So it seems as if our man was able to return to business in Manchester. Bound in half calf over marbled boards. Handwriting quite legible.

***

Posted on Bookman’s Log, presented here by permission of the author. Pictures: Bookman’s Log.