Tip Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America

The American Gift Book

By Kevin Mac Donnell

One Guy's Theory of Gift-Giving

The origins of the American gift book are rooted in the ancient custom of gift-giving and courtship ritual, and the evolution of the literary anthology. Gift-giving probably originated with a primitive man courting a primitive woman with brightly colored pebbles gathered from a creek bed not far from the safety of his cave. With time, less primitive women could only be wooed if the pebbles were chipped in interesting patterns. Today's sophisticated woman requires that they be faceted with great precision, and colored stones won't do - they must be absolutely and flawlessly clear, and should be stuck in metal settings that don't rust or turn green. That's my theory of the evolution of courtship and gift-giving, but it has one flaw: It would seem to me that those high-maintenance cave-women would have found few cave-guys with the time or inclination to gather and chip pebbles when they had more important things to do like gather food, fend off predators, and invent things like the wheel, beer, and poker. And with less food, more predators, and no poker winnings wouldn't those demanding cave-women and their distracted cave-suitors have vanished from the genetic pool, leaving us today with sensible men and women? Tragically, that's not how things have turned out, and I am not ashamed to say that I mourn for the good old days.

New Year's Gift-Giving

Let's toss those pebbles aside for a moment. By the time of the invention of printing with moveable types in the mid 1400s, the custom of giving gifts as New Year's presents was probably well-established in England, and by 1520 Sir Thomas More commented that "it is and of longe time hath bene... a custome in the begynnyng of the new yere frendes to sende betwene presentis... as the witnesses of their loue and friendsship..." Sir Thomas apparently did not spread enough New Year cheer around; just fifteen years later he was beheaded, not a very utopian fate. In 1520, 1521, and 1523 (and probably in other years, copies of which have not survived) THE DYETARY OF GHOSTLY HELTHE was published by Wynkyn de Worde, successor to England's first printer, William Caxton, as a New Year's greeting to his family and friends. Hardly a year went by from that time on when books were not printed in England for the specific purpose of gift-giving at New Year's. Nearly forty such books were published between 1520 and 1603, not counting re-issues, all with New Year's greetings explicitly printed in their title or preface. Most of these books were guides to health or religious tracts. The idea behind them was to wish good physical and spiritual health to the recipient, and the dedications in many of these volumes make clear that most of the intended recipients were female.

Literary Anthologies

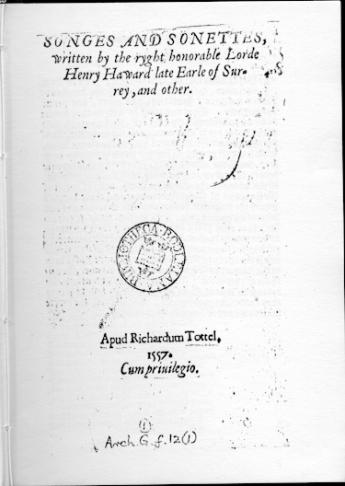

At the same time New Year's gift books were becoming popular, the literary anthology was finding its way into print in England as well. The first literary anthology was `The Greek Anthology' which was first compiled about 60 BC. This anthology went through numerous manuscript editions and in 1607 a tenth century version was discovered in the Palatine Library at Heidelberg. It consisted of roughly 6,000 short pieces by more than 300 writers, and although abridgements were published from time to time, the complete text did not appear until 1813. As early as 1526 a collection of short stories appeared, A HUNDRED MERRY TALES, but its authorship is unknown, and it may even represent the work of a single author. In 1557 the first English poetical anthology was published by Richard Tottel in Temple Bar, London, called SONGS AND SONNETS, forever known as `Tottel's Miscellany.' Only one surviving copy is known with the first edition colophon intact, so collectors, regardless of their budget, will have to settle for later editions. By 1597 there is clear evidence of how Tottel's anthology was being used. In Shakespeare's `The Merry Wives of Windsor,' Slender, one of the unsuccessful foolish suitors of Anne Page, wishes that he had a copy of Tottel to assist him in his courtship. But he doesn't have a copy, and his courtship goes all wrong, and he ends up carrying off a boy disguised in robes as a girl. Such were the pitfalls of courting without a copy of Tottel safe at your side. By 1604, the grave-digger in `Hamlet' was singing a song from Tottel's Miscellany, an indication of how widely popular and familiar the work had become among all classes of Englishmen. By 1600, Shakespeare himself had been anthologized during his own lifetime in Nicholas Ling's ENGLAND'S PARNASSUS, which contained ninety-one extracts from the Bard's works, along with poetry by his contemporaries: Drayton, Jonson, Marlowe, Spenser, and other Elizabethans. The previous year Ling had published a thick little pocket-sized compendium of extracts from the "flowers of antiquities" called WITS THEATER OF THE LITTLE WORLD. A steady stream of anthologies has flowed ever since.

European Models and Rudolph Ackerman

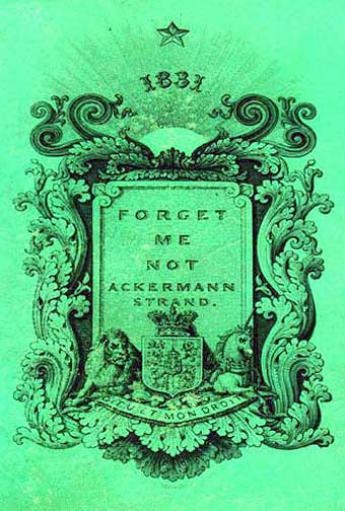

In France the first gift book may have been ALMANACH DES MUSES, first published in 1765. This format was copied in Germany in 1770 with the publication of MUSEN-ALMANACH. In the 1790s some anthologies appeared in England that were clearly intended to be given as gifts, like ANGELICA'S LADIES LIBRARY, OR PARENTS AND GUARDIANS PRESENT (1794), which was followed by THE ANNUAL ANTHOLOGY (1799, 1800), edited by Robert Southey, and including twenty-seven poems and epigrams by Coleridge, plus contributions by Charles Lamb and Southey himself. A third volume was planned, but never appeared. These proto-gift books did not start a trend, and I know of no similar anthologies published in England during the next two decades. In the early years of the nineteenth century in Germany, some gift books (taschenbuch) were being issued in glazed paper boards, and in 1822 Rudolph Ackerman used those as his model when he published the first English gift book, the FORGET ME NOT, which he would publish without interruption for the next twenty-five years. Gift books like Ackerman's, which were issued year after year, became known as gift annuals, literary annuals, or simply "annuals." Since not all "annuals" were exclusively literary in their content, I will use the term "gift annual" to describe them as a subset of the broader family of gift books. Ackerman called his gift annual "a new class of publication in this country" and dressed his earliest issues in bright lime green glazed printed boards, with steel-engraved designs on the covers and spine, and he enclosed each volume in a delicate box which had a lime green glazed label on the front and back printed identically with the book itself. Ackerman combined fiction and poetry from a mixture of famous and obscure authors, together with handsome steel-engravings, and a "presentation plate" at the front, and made clear on the title-page that his book was intended as "a Christmas and New Year's present." In both the content and the intent, Ackerman's work combined the old custom of New Year's gift-giving with the equally long tradition of literary anthologies, and added to these the more recent custom of Christmas gift-giving, and the success of his model proved the commercial possibilities of such a venture.

The First American Gift Books

Toward the end of the eighteenth century in America, the first American literary anthology had been published, AMERICAN POEMS, SELECTED AND ORIGINAL (Litchfield, 1793), which was quickly followed by THE COLUMBIAN MUSE the next year. Up until that time, America imported most of its literature from England, but by the time Ackerman published his first gift book in 1822, pride in American literature was on the rise, and it took just a few years before the first American gift book followed. Two gift books appeared in America about this time (THE WREATH, 1821, and THE ALBUMN [1823]), but they included no American content. THE PHILADELPHIA SOUVENIR appeared at the end of 1825 (dated 1826), edited by John E. Hall, who explains in his preface that he was sitting by his hearth reading a copy of poems by the Irish poet and lyricist Thomas Moore when "the entrance of a bookseller put an end to this dialogue with myself." The brash bookseller (a proud tradition carried on by some booksellers to this very day) "threw on the table several volumes with the titles of `Souvenir,' `Forget Me Not,' `Christmas Gift,' etc. - miscellaneous collections of literary efforts by various hands." "These," said the bibliopole, "are now all the go, in London. You may say what you will about American literature; but give me one of Ackerman's `Souvenirs,' and you are welcome to all our domestic manufacture." Having thrown down the gauntlet, so to speak, the bookseller was then confronted by Hall who showed him examples of American literature and proposed publishing a similar collection composed entirely of writings by Philadelphians, with the result that "the bookseller thought well of this scheme, and we agreed that the undertaking should be commenced without delay." Hall's patriotic effort can rightfully claim the title (by just days) of the first American gift book, but it died with the first issue and never became a gift annual.

The honor of first successful American gift annual must go to THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR, which was first published in December, 1825, also in the city of brotherly love, and continued until 1832. Ackerman's gift annual was certainly the model for THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR just as it had been for Hall's gift book. The size, format, style, and even the color of the glazed paper, were identical to Ackerman's volume. When placed side by side with FORGET ME NOT, it is hard to imagine that THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR was an American production and not a volume prepared by Ackerman for the American market.

As soon as THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR appeared, other new American gift books quickly followed, and by the time of the Civil War, a little over 1,000 yearly volumes had appeared. Consistent with the traditions which gave rise to the English gift book, they were typically given as Christmas or New Year's gifts, and they were frequently used in courtship, but in their blend of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, and steel-engraved illustrations, they gave voice to the rising pride in American art and literature.

At the time the first ATLANTIC SOUVENIR appeared, most of America's literary giants were still children, or else at the very beginning of their careers. Irving at 53 years old and Cooper at 37 were well-known authors, but Emerson at 23 and Hawthorne at 22 trailed far behind, with their first books still years away. Poe, Longfellow, Holmes, and Whittier were pimply-faced teenagers. Especially Poe. Melville, Whitman, Thoreau, and Lowell were not yet ten and didn't even like girls yet (Whitman never did, especially if they wrote gift book poetry). And Emily Dickinson had not begun tip-toeing toward Immortality.

II. THE NATURE OF AMERICAN GIFT BOOKS

Courtship in America

Besides riding the rising tide of pride in things American, American gift books also reflected an expanding literacy rate among American women (even if many gift books sat unread on parlor tables as genteel Victorian bric-a-brac). They both reflected and influenced American courtship rituals as well. Every proper young man could safely give his beloved a gift book, and nearly all gift books came with a "presentation plate" inserted at the front for the sole purpose of inscribing the book as a gift. Prefaces to gift books went to great pains to assure buyers that the contents would not offend the most tender sensibilities, although by the time THE GIFT was publishing Poe's macabre stories in the 1830s, this would seem an odd assurance. I know of at least one husband who might have felt betrayed by such assumptions after inscribing a copy of THE GIFT for 1843 to his wife. That gift annual contains Poe's `Pit and the Pendulum' and on the front inside cover in a bold contemporary hand are the words: "This is a mistake."

To avoid such mistakes, many gift books made clear their intent by their titles, and flowers were a favorite source of names for gift books and annuals. One important part of American courtship ritual was the highly elaborate "language of flowers" in which hundreds of different flowers had very specific meanings, all well-known to nineteenth century women (and hopefully, a few men). A suitor had to take care what kind of flowers he put into a bouquet, taking note of their species, their color, their arrangement, and even which flowers were buds or open blossoms. A fully blossoming moss rose signaled rampant sensuality, while a white rose bud signaled that a girl was to young for love. A lily stood for purity, a wild geranium for piety, and a sunflower for steadfast devotion. Many American gift books took on the names of flowers appropriate to courtship. Some were named more generically: THE BOUQUET, THE WREATH, THE GARLAND. Others were specific: THE WOODBINE, THE WINTERGREEN, THE CROCUS, THE ROSE BUD, THE ROSE OF SHARON, THE PRIMROSE, THE AMARANTH, THE MOSS ROSE, THE LILY OF THE VALLEY, THE MAGNOLIA, THE EVERGREEN, THE DAHLIA, THE HYACINTH, THE IRIS, THE LAUREL, and THE VIOLET. One clever gift annual, THE DIOSMA, called itself a perennial rather than an annual, but buyers did not pluck enough copies from the shelves of bookshops, and it withered away after one season. Sometimes your wares won't sell no matter how well you petal them.

If a young man suspected the object of his affections was the great-great-great-grand-daughter of one of those demanding cave-women who did not speak the language of flowers, he did not have to wander very far from his own cave to find gift books called THE DIADEM, THE OPAL, THE JEWEL, THE PEARL, THE RUBY, and a plentitude of gift books with the word "gem" in the title.

Gift Books With a Cause

Flower and gem motifs were ideal for courtship, but another direction taken with American gift books were those issued to promote special causes. THE OFFERING (1829) was intended to raise money for "infant education." AUTUMN LEAVES (1853) was issued to raise funds to help the poor. AUTOGRAPH LEAVES OF OUR COUNTRY'S AUTHORS (1864) was sold to raise money to help injured soldiers and their families during the Civil War. Several, like THE LIBERTY BELL (1839-1858) were issued to aid the anti?slavery cause, and still others were issued to promote other social agendas like the temperance movement or political parties. One, THE EXCELSIOR ANNUAL (1849) was issued to show off the creative writings by students in the New York City schools, and consisted only of the writings of children. It is apparently the first anthology ever published devoted exclusively to the writings of children.

Gift books with religious content were legion, and were appropriate gifts for married women and relatives. Still other gift annuals were full of morbid prose and poetry intended to comfort people faced with the loss of a loved one. The famous engraver and publisher John Sartain produced some memorably sad illustrations for gift books, dubbed "die-away" illustrations by Mark Twain. Lydia Sigourney became famous for her sentimental poems on death, especially those about dead children, and her epitaphic effusions were as certain to follow death as rigor mortis when some friend, neighbor, local politician, or national figure died - except that her poems came to her quicker than rigor mortis came to the corpses that inspired her. However, death themes in gift book fiction were not always so comforting as the poetry. In a short story in THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR, all twenty-three characters die off in every possible way - including the narrator. In another, the entire world is destroyed by a comet, which naturally raises serious questions about the vital status of both the narrator and his intended audience. It's hard to know whether to laugh or cry at some of these gift books, and it's clear people did both.

The Rise of Regional Literature

Still another American phenomenon reflected by American gift books is the rise in regional literature. A number of gift books were issued as collections of "metropolitan literature" narrowly focused on a local literary landscape rather than a national one. In fact, John Hall's THE PHILADELPHIA SOUVENIR, the first American gift book, was compiled from the writings of Philadelphia writers. Most of these regional gift books were less successful than the others kinds of gift books and while other gift books sometimes lasted ten or fifteen years or even longer, the longest-lived regional gift book was THE BOSTON BOOK, which managed to last only four issues, scattered between 1836 and 1850. Besides Boston and Philadelphia, other cities that produced regional gift books were New York, Baltimore, New Orleans, Charleston, New Haven, Portland, Detroit - and the states of Rhode Island, Maine, and New Hampshire.

Popularity and the Spread North & South

American gift books circulated in numbers as small as a few hundred copies (THE LIBERTY BELL) and editions as large as 10,750 (THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR at the peak of its popularity), and peaked in popularity in 1848, 1850, and 1851, when thirty-one different gift books were published in each of those years. English gift books had peaked in popularity in 1831 when sixty?two different issues appeared, but had declined to fifteen per year by 1846, just as American gift books were approaching their zenith. From America, gift books had spread earlier to Canada (THE CHRISTIAN REMEMBRANCER, Montreal, 1832) and South America (AQUINALDO PUERTO?RIQUENO, COLECCION DE PRODUCCIONES ORJINALES EN PROSE Y VERSO, Puerto Rico, 1843).

In the 1850s American gift books rapidly declined in popularity. One reason was that other publishers had gradually recognized the marketing advantage of publishing books toward the end of the year to catch the Christmas season. This flooded the market with competition. The practice of post-dating was also widely adopted, which extended the competition into the coming year. Even worse for gift book publishers, and not without irony, was the fact that many of the authors who owed their fame in part through the exposure of their writings in widely-read gift books, were now publishing books of their own every year that were both popular and perfectly suited for gift-giving. Gift book publishers had become victims of their own success, or rather, the success of their contributors. And to make matters worse, as gift book publishers went out of business the plates of many of their books were sold off to other publishers who then reprinted the contents under new titles. There was an explosion of such reprints in the 1850s, which further eroded the public's faith in the integrity of gift book contents. By the Civil War there were no gift annuals still being published, and the few gift books that were published after the 1850s were one-time publications, usually published to raise money for a charity of one kind or another.

Women Writers

American gift books were not only the gift of choice for sweethearts, sisters, and mothers, but they also gave women a venue for their creative writings. Female authors are well-represented in nearly every American gift book, and they dominated some. One gift book, SELECTIONS FROM FEMALE POETS, A PRESENT FOR LADIES (1836) was devoted exclusively to female poets. Even in the gift book of children's writings mentioned earlier, the girls outnumbered boys, thirty-four to twenty-three. The vast majority of these female "scribblers" (Hawthorne's word) never made a name for themselves, but a few others like Lydia H. Sigourney and Frances S. Osgood achieved great popularity in their day, thanks in large part to their prolific gift book poetry. Still others, like Elizabeth Barrett Browning made appearances in American gift books early in their careers. One poetess whose work appeared in gift books and equals Browning's was Maria Lowell, the wife of James Russell Lowell (himself a contributor to gift books), but she died young before having established a large enough body of work to achieve fame. Last and certainly not least, others like Harriet Beecher Stowe and Mary Baker Eddy became famous later on for reasons having nothing to do with their participation in the gift book era. Yet, despite these notable success stories, most of the poetesses were full of pious tripe, and Walt Whitman was justified when he commented on gift book poetry and asked, "Do you call those genteel little creatures American poets?"

III. CONTRIBUTIONS TO PUBLISHING HISTORY

Publishers

Gift books attracted the attention of most major publishers: Carey & Lea (Henry C. Carey), Carey & Hart (Edward L., Henry's brother), William D. Ticknor (later Ticknor & Fields), Phillips & Sampson, John P. Jewett, John Bartlett, James Munroe, Appleton, Lippincott, Wiley & Putnam (later George P. Putnam), and others. The only major publisher strangely absent from the roster of gift book publishers is Harper & Brothers. A perusal of several Harper histories fails to reveal any specific reasons why they did not participate in the gift book market. Besides Putnam and Appleton, other smaller New York publishers like John C. Riker, Leavitt & Allen, and Nafis & Cornish were extremely active in gift book publishing. Perhaps Harper felt the market was already saturated; 30% of all gift books were published in New York. An even more likely reason is that Harper's was a huge publishing firm, and unlike nearly every other American publisher they consolidated all of their production operations under one roof (editing, type?setting, plate?making, printing, collating, sewing, casing, binding, and shipping); they were geared toward the rapid mass?production of inexpensive books. Gift books, with their multiple contributors, many steel plate illustrations, and elaborate bindings, were labor intensive and time?consuming, and did not fit the standard Harper production model that depended on economies of scale that did not exist in gift book manufacture. While the average cloth?bound novel or collection of verse cost about 75 cents to $1.25 before the Civil War, the average gift book cost $4 to $5, and the larger more elaborate volumes could cost up to $20, an enormous price for a book in the 1830s, 40s, and 50s. Profit margins on gift books were higher than those for other publications, but so were the risks, and Harper was risk?averse.

Gift books, always intensely competitive, were often among the first books to exploit new trends in publishing in order to attract attention and sales. Gift books, both English and American, were among the first books issued with boxes, dust jackets, gilt?stamping on cloth, embossed leathers, stenciled leather, and pre?ornamented cloth. In America, they were also the first publications to establish the custom of post?dating a volume published at the end of the year for the holiday season, and they were the first publications to motivate publishers to engage in clever deceptions to remainder their unsold merchandise.

Book in a Box

Some French and German books had been issued in boxes as early as 1820, and I once handled an original collapsible leather and silk box for a leather?bound English book from the 1790s. For centuries Middle Eastern manuscripts have been preserved in leather pouches with shoulder straps, and various 18th and early 19th century pamphlets have been found from time to time in envelopes with imrpints by the publisher. But Ackerman's use of boxes designed to match his bookbindings set a trend that has endured down to the present day. Ackerman was closely copied by THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR and THE TOKEN and those two American gift books are the earliest known American publications issued in a box.

Gilty Splendour (with apologies to William Cowper)

Publishers of gift books did not like the added expense of making a box to protect the delicate boards bindings, and as soon as they were able to perfect the process of printing gilt on cloth, they quickly made the change. Gilt?stamping on leather dates at least as far back as 1459 (on a 1457 manuscript bound for King Rene of Anjou [cf. THE BOOK COLLECTOR 7:3 (Autumn, 1958) pp. 265?68]. The application of albumen (egg white) or glair (albumen mixed with vinegar) to leather allows the gilt to adhere to the leather, and is a fairly simple process; after gilding, any excess glair is simply wiped away without leaving a stain, but finding a way to make gilt adhere to cloth without staining the unsized cloth with excess glair was a problem not solved until cloth sizing improved. In France, some books from the 1790s have been noted with gilt?stamped silk end papers, so it is clear that the problem of getting gilt to adhere to silk had been solved elsewhere, but it is peculiar that only end papers were gilt in this period instead of the covers or spine; it is possible that the adhesive used to apply the backing paper to the silk end papers acted like a sizing, which then allowed the silk to be more easily gilded. It has also been speculated that the arming press needed improvements that stood in the way of gilding cloth, but it is hard to imagine what those improvements might have been since the arming press had been used to gild coats?of?arms on leather bindings for many year s. But by 1820 some French almanacs were being bound in gilt?stamped silk, so the French had solved the problem by that date. C'est la vie.

In England, both THE AMULET and THE KEEPSAKE appeared in 1828 in gilt?stamped silk. In America, THE MEMORIAL for 1828 was likewise bound in gilt?stamped silk. Some earlier English and American publications have been found in gilt?stamped cloth, but the common practice of binding up unbound sheets ten and fifteen years after publication makes dating such bindings a speculative endeavor. The date of the imprint cannot stand alone as proof of the date of binding, and in cases where an original binding is known for a particular book (most often, plain boards with a paper label) a variant binding in gilt cloth is even less likely to be contemporary with the plain original binding. Take for example, the publications of William Pickering, who is generally credited as being the first English publisher to use cloth for book?bindings (his Diamond Classics Horace of 1820 was the first). His imprints are often found in gilt?stamped cloth, some of which clearly date as early as the 1840s, but it should be remembered that unbound sheets of his publications were still being sold in bulk in London bookstalls in the 1920s. Thus, a Pickering imprint of the 1820s in gilt cloth might have been bound in the 1840s, or the 1880s, or the 1920s. Publishers themselves often hold old stocks of unbound sheets for decades before binding them. I have handled Ticknor & Fields imprints of the 1850s bound up by their successors, Houghton, Mifflin & Co. in the 1880s. In such a case as this, the publisher's spine imprint and blindstamped designs prevent any confusion, but the rather plainly stamped cloths of the 1820s and 1830s closely resemble the plain stamping found on "binder's cloth" jobs of the late nineteenth century, and some of the more common cloth types used in the early years of the nineteenth century (A cloth, AR cloth, C cloth, P cloth, T cloth, etc. ??see the bibliography for sources that illustrate the major cloth types) were still in common use fifty and sixty years later.

But gift books, being time?sensitive in the extreme, provide a reliable means of dating bindings. Gift books were not inexpensive, and no young man giving a gift book to his sweetheart wanted to be caught giving her last year's gift annual. Once the year had passed, a gift annual's chances of selling were all but nil, and in the frequent cases where publishers of gift annuals were stuck with the task of selling old stock, they went to great pains to disguise their wares as new stock, going to absurd lengths to change dates in the text and on the bindings. Motivated by a desire to sell a new?looking but out?of?date publication, the last thing a gift annual publisher would do is put an original publication date on a later binding. It was the custom to put the date at the foot of the spine on early gift annuals, and these can be taken as reliable indicators as to the date of binding. Those gift books dated 1828 were issued at the end of 1827, and in the case of THE KEEPSAKE the date of that binding can be firmly established by independent evidence ??the publisher's braggadocio in the preface to THE KEEPSAKE for 1829. He proudly lists the things he claims were improved from last year's volume, mentioning that "the binding and gilding [were] materially improved." Likewise, independent evidence exists for THE AMULET, which was reviewed in `The London Mirror' at the end of 1827. The critic complained that the crimson silk "was somewhat gay for so grave a title." The subject of which cloth?bound books were the first to be stamped in gilt has been vigorously debated for nearly a century, and some authorities distinguish between silk and coarser book cloths like muslin and calico, but among all the prospective candidates, only THE KEEPSAKE and THE AMULET for 1828 can stake a firm claim to their dates. In America, the claim goes to THE MEMORIAL for 1828, which was bound in blue silk, and it was followed by the issues of THE TOKEN for 1829 and 1830. I have seen THE TOKEN for 1829 in green silk and the TOKEN for 1830 in both green and red silk bindings. Very Christmasy.

The Earliest Known Dust Jacket

While the publisher of THE TOKEN explained in his preface that binding the book in silk eliminated the need for a box, the publisher of THE KEEPSAKE apparently did not entirely agree that silk needed no protection from dust or light and chose to swaddle his silk?bound KEEPSAKES in printed dust jackets. Exactly when THE KEEPSAKE was first issued in a dust jacket is unknown, but in 1934 John Carter found a copy of the 1833 KEEPSAKE in a printed dust jacket that was designed to enclose the book completely. This discovery still stands today as the earliest known survival of a printed dust jacket on a book. It was printed on the front and back panels and left blank on the spine. From the soiling and dust stains on this jacket it is clear that it was originally folded around the book in correct alignment, but later removed and refolded incorrectly, and then stored this way for a very long time. It is fortunate that Carter photographed this jacket, because in 1952 while being shipped to the Bodlean Library, it was supposedly lost in the mail; however, the book (without jacket) survives at the Bodlean Library, so it would seem that a shipping clerk may have tossed it in the trash. Carter's photo of this remarkable piece of publishing history appears in `The Library' 26:2 (June, 1971) facing p. 122. No dust jackets are known on American gift books before the Civil War. Long after American gift annuals had vanished from the marketplace, a slender volume was published to raise money for the preservation of a Boston landmark, and POEMS OF THE `OLD SOUTH' (1877) is the earliest American gift book known in a dust jacket (which was printed only on the front panel).

Embossed Leather

The most noticeable feature of American gift books are their embossed leather bindings. The earliest issues in printed boards and gilded silk are not without charm, but some of the embossed leather bindings are quite attractive and even impressive. The demand for leather?bound gift books preceded the ability of gift book publishers to mass?produce them, and some early gift books are found in contemporary leather bindings prepared for their original purchasers ("bespoke" bindings) who felt that a book given as a gift should be dressed up in something fancier than brightly colored boards or cloth. Cost was one factor that made publishers hesitant to bind their books in leather. It cost Carey & Lea about 26 cents to bind THE ATLANTIC SOUVENIR in boards, but embossed leather cost 44 cents per volume, a substantial increase, and they were already facing even greater expenses paying their contributors and steel engravers.

Another reason for the delay was technology. Stamping a design like a simple rule border or spine lettering into leather did not involve compressing a large surface area, but embossing, where a large surface area is compressed in order to leave a "raised" design in relief, required both heat and a great deal of pressure. A simple arming press (so named for its use in stamping coats of arms on bindings) did not allow enough pressure, even after the old screw mechanism had been discarded in favor of a system of levers in 1832. Some of the very earliest embossed bindings of the 1820s are rather lightly embossed compared to the much deeper, sharper, and more detailed embossed bindings that followed just a few years later. Those lightly embossed leathers may have been produced after the toggle?action press was refined (1822). The toggle?action created pressure when the bar of the press was pulled, which drew two hinged levers of equal size into straight alignment, converting downward energy from the horizontal pull of the bar. The rack and pinion action that soon followed further multiplied the pressure exerted by a pull of the bar, and it was finally possible to exert enough pressure to produce an attractive relief design. Heat was also required for embossing, and that heat was supplied by gas pipes that were fed through the bottom of the press, so that the brass or steel embossing plaque or die (also called a block or intaglio plate) was in the bed of the press and the cover to be embossed had to be laid over it, held in alignment by a cardboard guide, in much the same way the tympan and frisket of a handpress held the sheets in correct register during printing. Once the leather was positioned a counter?die was pressed down on the leather to force it into the shape of the plaque. Some counter?dies were machined from brass, but more often they were composed of a stack of millboards cut to the approximate dimensions of the plaque. Even with the added power of improved embossing machinery, it was still not enough power to emboss an entire casing in one pull of the bar; it still took three separate pulls to emboss the spine, the front cover, and the back cover (which made the process slow and added to the production cost). Technological improvements improved the quality of the product but did little to speed up the manufacturing process.

Not only was the process slow, but the leathers used had to be chosen with care. Calf skin was too tough to use in embossed bindings, so sheep skin and goat skin (morocco) were most often used. In order to save money and further reduce the need for extra pressure, sheep skins (and less often, goat skins) were often split. The resulting split skins (skiver and roan) were thinner and not so durable as a full skin, but they could be more easily embossed, and they required less skiving (thinning or shaving) at the spine ends, joints, corners, and turn?ins where leather had to be skived by hand so it would lay flat and fold evenly. Skiver was the outer (or "grain") layer of the split skin and was a bit stronger than roan, but it had a natural grain where the hair had been removed (with lime, bleach, or sumac) that resisted the embossing plaques, especially in the areas that were intended to be flat between the raised designs. Roan was the inner (or "flesh") layer of the split skin and was softer and could be more easily embossed, and because it had no grain, the flat areas of the design would look flatter, and were sometimes nearly as reflective as a mirror. The roans used in normal bindings were usually lightly embossed with an imitation grain impressed from an electro?type plate in a cylinder press [see my previous article in `Firsts' (September, 1998) describing the process of making these plates], but the roans used for embossed bindings were usually left natural so they would better accept the embossed design. It is sometimes possible to determine whether roan or skiver was used, and even whether the split skin was sheep (often called "turkey morocco") or goat (true morocco) by closely examining the flat areas of an embossed binding for traces of the original grain. In researching the various kinds of hides and processes used it should be remembered that gift book publishers did not always use uniform terminology in their advertisements or business records and were often deliberately misleading, and binding historians of today still debate the details of the processes and don't even agree on a common terminology. To determine how embossed bindings were assembled, binding historians have literally dissected some shabby original bindings to learn their secrets. Such study has revealed that some embossed leather bindings were embossed as a casing and then attached ("cased") to the text block; in other instances, the boards were attached to the text block in the traditional manner and the leather was then applied, and finally embossed; in still others the leather was embossed before being attached to the boards or casing. But regardless of the assembly method the inherent weakness of the roans and skivers remained, and embossed leather gift book bindings are notorious for scuffing easily and falling apart. One contemporary commentator on embossed bindings estimated that they could not stand up to more than a few months of sitting on a shelf.

One?hundred and fifty years later (that's 1,800 months), it would be unrealistic to imagine assembling a collection of gift books without accepting some books in less than pristine condition. But such a collection will make a handsome shelf. The designs on these embossed bindings render them among the most attractive American bindings of the period. Courtship scenes, pastoral scenery, patriotic eagles, gothic cathedral windows, geometric machined designs, classical and religious imagery, and intricate filigree and floral patterns are the main elements in the designs used on embossed American gift books. The plaques used to emboss bindings on American gift books were also used to emboss many other books, both English and American, but many of these designs were originally made for the gift books on which they were used, as evidenced by the name of the gift book in tiny letters on the plaque itself, or the fact that the earliest use of a given design is on a particular gift book. In some instances, the publisher's costbooks have survived and show the cost for the engraving of the plaques and even the names of the die?sinkers who did the work. And many of these embossed designs have the name of the die?sinker engraved in the plaque itself, hidden in the design. Lovers of embossed leather bindings will want to consult Edwin Wolf's superb study of these bindings.

Stenciled Leather

Another binding innovation that was pioneered by gift books is the stencilled leather binding. In this case, stencils were used to apply colors to a binding before gilding, to create the impression of the much more expensive process of genuine inlaid (more often, onlaid) leather. Some of the stencils could have been better aligned, but in general the results are beautiful. Besides books, stenciling was at the height of its popularity in the 1840s and is found on American furniture of all kinds, Hitchcock chairs being the best?known examples, and boxes, dressers, beds, iron machinery, carriages, street signs, porches, and the interior walls and floors of stylish homes were being stenciled. THE EXCELSIOR ANNUAL, THE OPAL, and THE DIADEM are a few of the gift books that are recorded in stenciled bindings, but the best?known example is the magnificent binding on THE RAINBOW (Albany, 1847 ??not to be confused with a book of the same name published in London in 1830 in a gilt?stamped silk binding). Despite the popularity of stenciling on other objects it never seemed to catch on with books, and sales of this volume were terrible; roughly half of all surviving examples are of the 1848 remainder issue, and there is no record of Harrison publishing another book.

Pre?ornamented cloth

One other binding innovation that was used on an American gift book was pre?ornamented cloth. Publishers thought they could save a lot of money if they could buy pre?ornamented cloth designed in several standard sizes that would only require them to add some gilt stamping. Pre?ornamented cloth had the design stamped in relief so that it was raised, giving the appearance of embossing, rather than conventional stamped cloth where the design is recessed. Because pre?ornamented cloth could lay flat on a board, it was not necessary that it be applied to the board first. Conversely, stamped cloth would hold its shape only if stamped after it had been applied to a board. Pre?ornamented cloth began to appear in 1835 and the trend was over by 1846, with twenty known patterns having been used on about three dozen different publications. Publishers quickly found out that aligning the cloth for gilt?stamping and then aligning it again for gluing to the boards (regardless of the order in which they were gilt, glued, or cased) was a time?consuming and therefore costly process, and judging from the surviving examples, the results were not always satisfactory, with gilding out of alignment with the cloth designs, and cloth?designs out of alignment with the book itself. THE BOSTON BOOK for 1836 used conventional stamped cloth, the next volume, for 1837, used pre?ornamented cloth, but when the next volume was issued in 1841, conventionally stamped cloth was used once again.

The First Photograph in an American Book

While most early gift books were illustrated with steel "engravings" and others were illustrated with lithographs, an actual photograph was used in one gift book, the first such use of a photograph in an American book. HOMES OF AMERICAN STATESMEN (1854; issued at Christmas, 1853) was issued as a companion to HOME OF AMERICAN AUTHORS (1853; issued at Christmas, 1852) which had been illustrated with lovely color and tinted wood engravings printed directly on the text paper in some copies, and printed on tissue in others. Like the 1853 volume on authors, the text of this volume was based on visits made to the homes of famous American statesmen, and the frontispiece consisted of an original salt print photograph ("crystalotype") of the Hancock House in Boston. Most copies have a pencil caption added below the photo describing it as "an original sun picture" ??capturing a properly exposed image outdoors in natural light in the days before light meters, automatic f?stops, and perfectly calibrated apertures was no small feat, and worthy of bragging rights. Some copies have the blindstamp of John Adams Whipple's studio, but the actual photographer was probably Whipple's assistant, James Wallace Black. This book is often found with Christmas, 1853 inscriptions which clearly establishes that this use of photography in a book precedes the photo found in a book once proposed as the first book to use a photographic illustration: Warren's REMARKS ON SOME FOSSIL IMPRESSIONS IN THE SANDSTONE ROCKS OF THE CONNECTICUT RIVER, published by Ticknor & Fields in May, 1854. We are fortunate that this particular photo exists, because the Hancock House was demolished in 1863.

Post?Dating & Remainder Techniques

Critical to the salability of gift books was their currency. Whether or not they were actually new books or fresh stock did not matter so much as the fact that they looked like new books or fresh stock. Publishers tried to estimate their sales as closely as possible, but when left with unsold copies at the end of the gift?giving season, they had to find ways to recover their costs. To begin with, books published "for" any given year were always published in October, November, or December the year before to catch the holiday gift?buying season, and this practice gradually spread to trade publications of all kinds. In fact, the wide?spread adoption of this practice by nearly all publishers by 1850 probably created more and more holiday competition with gift books and significantly contributed to their demise in the following decade. In a few instances, a title?page of a book "for" a given year might actually have the previous year's date in the imprint, or at the end of the preface, but more often than not, gift books were post?dated or not dated at all.

The most outrageous scheme for retreading a worn out gift book is the remainder technique used by the publisher of THE RAINBOW (1847). Many publishers used the same technique, but I know of no examples that carried it to the extremes of A. L. Harrison in Albany, New York. This seems to be the only book Harrison ever published, but the first issue of THE RAINBOW is a beautiful effort, a spectacular binding of brilliant bone white calf (nearly always aged to a beige hue), stenciled in terra cotta, green, and two distinct shades of brown, and elaborately gilt, with wildly patterned end papers printed on glazed paper. Harrison called this style of binding a "Patent stereographic binding" but there is no record of such a binding being patented by Harrison or anybody else. As with nearly all gift books, it appeared late in the year for the holiday season, and the book is "for" 1847, but the preface is honestly dated 1846. The spine of the binding, the vignette title, and the title?page itself are all appropriately dated 1847. But the book was a flop, and the publisher unloaded his unsold copies the following year by carefully pasting a tiny round label over the spine dated 1848, and he used a similar paste?over cancel to change the date of the vignette title?page from 1847 to 1848. He then hand?stamped an added "I" to the Roman numeral date in the title?page imprint, changing it from MDCCCXLVII to MDCCCXLVIII, and he erased the date in the preface and overstamped a 7 where the 6 had been. The most common form of cancel in a book is the removal of one leaf (the cancellandum) and the substitution of a corrected leaf (the cancellans) in its place. The most common reason for making such a cancel is to correct an error. But in this single volume Harrison used every kind of cancel except the most common kind (a paste?over slip, an erasure, a hand?stamp, and even a paste?over on the binding itself) and no errors were corrected; his only motive was deception. And he did not stop there. He apparently had left?over sheets and he bound those in bright pink calf, gilded them from the same brasses he had used on his 1847 copies, patched over the 1847 date on the spine with an 1848 label, substituted plain yellow glazed end papers for the fancy printed ones, and did not bother to stencil the binding at all. The sheets were canceled as he'd canceled the other remainder, and at first glance it might have looked like an entirely new edition. THE RAINBOW is the most over?wrought example of a gift book trying to look like a gift annual.

A less egregious example of remaindering is the last volume of THE TOKEN (1842). THE TOKEN had been a highly successful gift annual, appearing every year from 1828 to 1842, but the last six issues were published by five different publishers, a sure indication of a struggling enterprise, and the very last volume apparently sold even more poorly than those before it. To rid himself of the very last copies in 1843, the title?page date was crudely altered from 1842 by overstamping it to read "1842?3" and the binding was gilded with an ornament in place of where the date had previously appeared, and the embossed scene at the center of the 1842 covers was overstamped with a large gilt lyre. At first glance, the big gilt lyre on the covers made it look like a different binding, but the vignette title?page was left with the 1842 date intact, and the title?page change would not have fooled anyone. The publisher of that last TOKEN was crafty, but not so devious as the wily Mr. Harrison.

THE TOKEN for 1838 suffered a different fate, and died an even slower death. It was a handsome book with superb literary content (including five stories by Hawthorne), stamped rather than embossed, using excellent quality leather. The date of 1838 appeared on the spine in gilt, on the vignette title?page, and on the title?page itself. Sadly, this deserving book failed in the market, and left?over copies were bound in a coarse?ribbed cloth, stamped in gilt from the same brasses as the 1838 issue, but with the date routed out of the gilding brass. The dated vignette title?page was simply left out, but the title?page was unaltered. Four years later, after THE TOKEN came to an end, the printing plates of the 1838 issue were sold to a New York publisher who used them to print editions in 1842, 1843, 1844, and 1845. And three undated printings appeared in New York by other publishers during this same period, one with the binding dated 1845. The plates then found their way to Hartford, and editions appeared there in 1846, 1847, and 1850, plus one undated printing. This single issue of this dead gift book was followed by a dozen zombie editions in as many years, a possible record in the shameful annals of gift book remaindering, and it was not the only issue of THE TOKEN to be reprinted.

THE BALTIMORE BOOK for 1838 suffered the same fate as THE TOKEN for that year. It contained Poe's `Siope' but not much else. That, combined with the economic gloom of the Panic of 1837, killed all hope of sales, and it too was remaindered the following year. The 1838 issue was bound in full morocco with the date emblazoned on the spine, as well as the presentation plate, the vignette title, and the title?page. Unsold copies remaindered in 1839 are in cloth with the date 1839 on the spine, the presentation plate and vignette title?page removed, and the date on the title?page erased. The Baltimore publisher was more willing to deceive than his Boston counterpart in his attempts to make his gift book look like the second issue of a gift annual. But he apparently did not find a buyer for the printing plates, and that was that.

Steel Plates

Besides the bindings, one of the contemporary selling points of gift books were their illustrations, although most collectors today collect gift books for their bindings or their literary content. The art of making steel plates was perfected by 1810 and steel engravings were first used about that time to print bank?notes ??the fine detail of etched steel plates made such bank?notes difficult to counterfeit. Steel could be etched much finer than copper could be engraved, but more importantly for gift book publishers steel was far more durable. When an etched plate is inked, the ink must be carefully wiped from the flat surfaces, leaving only the ink in the etched channels of the plate. For darker areas in the image the plate was lightly brushed ("retroussed") with a brush or very thin scrap of muslin to spread a delicate web of ink between the lines of the etching. All of this had to be done between each impression, and when the plate was printed, the paper would pick up only the ink from the etched channels and the areas that had been retroussed. To prevent ink from drying in the finer lines of the plate between impressions, the entire plate then had to be wiped hard with a solvent, dried with more wiping, and a new coating of ink applied, etc. ??and this process repeated for each impression. Copper wore down each time the excess ink was wiped from the flat surfaces; steel did not. Copper also compressed with each impression taken during the printing process, but steel could last many thousands of impressions. This combination of superior detail and durability made steel?engraving ideally suited to the needs of gift book manufacture.

The finer detail of steel plates was possible because of the etching process used. Copper was most often engraved directly on the surface of the copper plate with a stylus and other tools (the "dry point" technique), a task made possible because copper was relatively soft. But this process did not result in such extremely fine detail as could be achieved by etching a steel plate. Copper could be etched, but as the plate wore down during printing much of the detail was lost. The hardness of steel made etching a necessity, but once the steel plate was finished, it would not soon wear out in use. The first step in etching was to cover the steel plate with a wax?like coating (called "ground" or "resist") and the original illustration was then copied by drawing it into the wax in reverse with a stylus. Next, nitric acid was poured over the plate and allowed to etch away the steel where it was exposed by the removal of the wax by the stylus. This process had to be repeated several times for most steel plates, to fill in finer lines, etch some lines deeper, or to add more shading. For stippled engravings, the stylus was put directly onto the steel plate itself to create the tiny dots or stippling effect after the etching was finished. Mezzotints were "rocked down" using a rocker, a round?ended tool with 40 to 120 teeth per inch. Background work was often accomplished using a ruling machine that would draw evenly?spaced straight or wavy lines as required.

The result of all of this preparation was that the best steel "engravings" could produce printed illustrations of nearly photographic quality and three?dimensional depth ??a high standard that gift book illustrations did not always meet. But the etching process, combined with stippling and mezzotinting, made it possible to faithfully reproduce familiar works of art, and the publishers of gift books quickly began to brag that the art they were reproducing in their books was not European, but American art. Certain artists and engravers were soon in vogue, and publishers who used illustrations from earlier publications or who copied European art soon found they had no market. Critics who reviewed gift books in newspapers and popular magazines devoted as much attention to the illustrations as they gave to the bindings or texts. Buyers of gift books often removed their favorite illustrations and framed them (a problem for collectors who prefer their gift books will all of their plates).

Given the time and costs involved in steel?engravings, it should come as no surprise that publishers tried to economize on this major expense whenever possible. Illustrations were sometimes used again and again in other gift books. And reviewers who caught a publisher rehashing old illustrations were quick to raise the alarm and urge readers not to buy that gift book. But not all book reviewers had eagle eyes, and the public has a short memory, so it is likely that publishers got away with it most of the time.

A few gift books also used lithographs and wood?engravings, and even fewer used hand?colored plates, tinted plates, embossed papers, or chromolithographed plates, but steel engravings were the first choice of buyers.

Early Examples of Printing on Tissue

While most gift books used steel engravings exclusively, Putnam tried to apply a technique that was relatively new to American books, and produced HOMES OF AMERICAN AUTHORS using both steel plates and wood?engravings. He printed his wood?engravings directly on the text paper in some copies, and on a coarse tissue or india paper in others, which he advertised as "proof" copies. Some of the wood?engravings were tinted and others were printed in colors. Putnam spared no expense on his fancy gift book, and I have located examples in at least nine different binding styles ??various leathers and cloths, some gilt, some blind?stamped, some with plain edges and some with gilt edges, some with recessed panels, and even one with the publisher's original clasps and catch plates on the fore?edge of the covers. This elaborate volume, whose companion volume has been discussed already, consisted of accounts written by various writers of their visits to the homes of famous (and some not yet famous) authors, and among the accounts is the first description in book form of Thoreau's experiment at Walden Pond. His stay there had been briefly mentioned before in a book, but not described in detail. The various bindings found on this book determined the price, which ranged from $5 in regular cloth, $6 in extra gilt cloth, to $7 in blind?stamped morocco, $8 in gilt morocco, and $12 for copies with the illustrations on tissue "proofs."

Despite all the care lavished on this book, Putnam's printers apparently did not fully understand the principles behind printing on tissue. Contrary to a common misconception, illustrations printed on tissue were not normally printed separately and then inserted onto a page. The usual method was to paste the tissue to the plate or page with a thin layer of wheat?paste before the image was printed. The added thickness of the tissue and paste allowed a fuller absorption of the ink in the plate and this, combined with the fine grain of the tissue itself, resulted in a sharper "bite" in the impression, and finer detail in the printed image. This was an especially useful technique in getting the maximum possible detail out of wood?engravings. But in every copy of this book I have examined (more than fifty copies) it is very clear that Putnam did it bass?ackwards. His tissue illustrations are trimmed, often too closely, around the image itself, and others were cut in a square after being printed, in such a way that it makes clear that they were printed separately and then inserted onto the pages. Most show trimming into the outer edges of the printed surface itself, and had the tissue been on the page at the time of printing, the printed image would have overlapped onto the text paper beyond the edge of the tissue, or else bled into the edge of the tissue. These "proof" plates do show greater detail than the ones he printed directly on the pages themselves, and the result (except for the sloppy trimming in most copies) is the same, but he did it the hard way.

The article was published in Firsts and on www.ABAA.org. It is presented here by permission of the author.