Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Tavistock Books

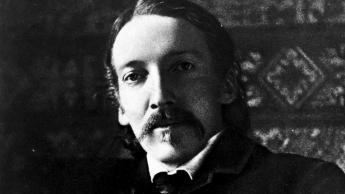

Robert Louis Stevensonâs Shocking Christmas Tale

By Vic Zoschak

We Interrupt your Weekend Activities to Bring You this Very Important Blog Honoring this Friday the 13th Birthday…

On November 13, 1884, Robert Louis Stevenson received a request from the Pall Mall Gazette. The editors wanted a sensational story to publish in its special Christmas issue, and they offered Stevenson a generous £5 per 1,000 words. Woozy with morphine taken for a chronic cough, Stevenson complained that he wasn’t up to the task of writing something new. So he dusted off a piece he’d written back in 1881: The Body-Snatcher.

While the book fit into the long-standing tradition of telling scary stories at Christmas, it also went far beyond the spooks of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol or The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain. The Pall Mall Gazette ran ever increasingly dramatic advertisements for the story, which finally appeared in its 1884 Christmas Special. In fact, some of the advertisements were so graphic, police actually stripped the signs from the sandwich-board men. Both grotesque and horrifying, Stevenson’s The Body-Snatcher was not only shocking for its lurid content, but also because in its pages Stevenson accused a highly respected surgeon of committing murder.

A Novella Ripped from the Headlines

In The Body-Snatcher, the character of Wolfe Macfarlane is a wealthy, fashionable London surgeon who hails from Edinburgh. Early in his career, he had served as assistant for a Dr. K…, who purchased the bodies of murder victims killed specifically for the sale of their corpses. Macfarlane himself even commits one of these murders.

Stevenson draws the novella’s inspiration directly on the true story of the Burke and Hare murders, which implicate a real-life Dr. K…., along with his assistant, Sir William Fergusson, who rose to the rank of surgeon to Queen Victoria. The implication that Fergusson might have committed murder like his fictional counterpart scandalized Stevenson’s readers. By this time, Fergusson had passed away, protecting Stevenson from a libel suit - and ensuring that the truth remained buried.

The Real Dr. K…

During the 1820′s, Robert Knox ran the most successful anatomy school in Edinburg. At the height of his career, the school had over 500 students. Endlessly ambitious, Knox wasn’t satisfied. He also built a private anatomy museum and pursued his own research interests. All these activities left Knox with one significant challenge: he couldn’t get enough cadavers.

At that time, the only cadavers that could legally be used for dissection were those of prisoners who were condemned to death and dissection - which wasn’t very many. Many doctors and medical students resorted to purchasing bodies from so-called “resurrectionists,” who were really grave robbers. They would remove bodies from cemeteries during the night and sell them to anatomy schools. Numerous doctors and medical students were actually charged with misdemeanors for possession of these ill-begotten bodies.

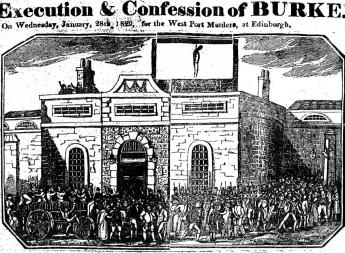

Given the shortage of bodies, a fresh cadaver garnered a high price: sometimes as much as £10. When a boarder died at William Burke’s lodging house, he and his associate William Hare decided to try selling it. It was so easy and lucrative, the pair decided to, in Burke’s words, “try the murdering for subjects.” They would go on to kill three men, twelve women, and one child. Robert Knox purchased every single one of these bodies.

Knox was especially pleased with the corpse of Mary Paterson. Her body was so flawless, he preserved it in whisky for three months before dissecting it and invited artists to capture her likeness. But there was one problem: when Burke and Hare brought Paterson’s corpse, one of Knox’s assistants recognized it: Fergusson. In his confession, Burke said that Fergusson “was the only man who ever questioned me anything about the bodies” and noted that he’d particularly inquired about Paterson’s.

A Sensational Court Case

But it wasn’t Paterson’s murder that drew the police’s attention, even though anatomy students recognized her. Rather, it was Madgy Docherty, one of Burke’s boarders. When Docherty went missing, two other boarders went looking for her … and found her body stashed under a bed. They immediately went to the police. Mary Paterson and James Wilson were also named as victims on the murder indictment against William Burke, Helen M’Dougal, William Hare, and Margaret Hare.

The press jumped to publish every bit of information available about the victims. Paterson was a resident at Magdalene Asylum, a home for at-risk girls similar to Charles Dickens’ Urania Cottage. James Wilson was a well-known street figure survived by his mother and sister. And Madgy Docherty was the only victim whose body was examined by the police. A thriving trade in hand-colored portraits of the victims quickly emerged, although only the ones of Wilson were actually drawn by someone who knew him.

Before the trial, the Hares agreed to testify for the prosecution in exchange for immunity. Burke and M’Dougal were tried on December 24, 1868. M’Dougal was acquitted, but Burke was convicted. On January 28, 1829, he was executed. In a turn of rather poetic justice, Burke’s body was dissected and exhibited publicly.

Knox Falls from Grace

Meanwhile, Knox was vilified for having purchased Burke and Hare’s bodies. He denied all knowledge of the murders, though his detractors pointed out that someone so accomplished in anatomy should easily identify a body that has died through violence. Furthermore, it’s simple to notice when a body hasn’t been pulled from a grave. Many researchers argue that Knox probably had an extensive network of body snatchers, supplying him with corpses not only from Edinburgh but also from Glasgow, Dublin, and Manchester. However, Knox claimed that his assistants (including Fergusson) handled cadaver acquisition on his behalf, so they were the ones who had actually purchased the bodies.

The public was unconvinced. On February 12, 1829, an effigy of Knox was publicly hung and quickly torn to pieces in the street. Popular ballads and caricatures reviled the formerly respected figure. Though Knox was cleared of any knowledge of the crime, his career crumbled. Unable to establish a new anatomy school, Knox resorted to translating French anatomy textbooks and writing for medical journals.

His assistant Fergusson fared much better. Despite the fact that he had even questioned Burke about the bodies, Fergusson was not called to task for his probable role in the entire affair. On the contrary, he moved to London and eventually established himself as a preeminent surgeon. It was not until Stevenson published The Body-Snatcher in 1884 that the public reevaluated Fergusson’s potential role in the whole debacle.

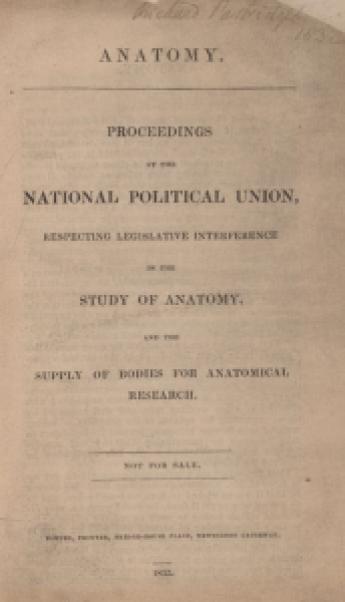

Legislation Quells Practice, But Not Public Fascination

The Burke and Hare murders, and others like them, paved the way for the Anatomy Act of 1832. As the cadaver shortage reached crisis in 1828, a Select Committee on Anatomy reported to Parliament. Chairman Henry Warburton drafted an Anatomy Bill that would allow schools access to unclaimed bodies of people who died in workhouses and hospitals. It failed in the House of Lords. But in 1832, John Bishop and Thomas Williams were also convicted of committing murder to get cadavers. Fearing an epidemic of similar murders, Parliament passed the Anatomy Act of 1832, expanding access to cadavers and establishing a system for documentation and inspection. The Anatomy Act did little to actually resolve the issues surrounding cadaver acquisition because many parts were intentionally vague. However, because a record of cadavers was created, it did eliminate the possibility of murder for cadaver sale.

By 1884, five decades had passed since the Anatomy Act went into effect. Yet the public still had an insatiable thirst for shocking episodes like the Burke and Hare murders, so it’s no surprise that The Body-Snatcher proved an overnight success. (And Stevenson probably regretted having refused the entire £40 payment for the work.) Stevenson would go on to explore the grotesque successfully in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, now perhaps his most famous work.

***

Posted on the Tavistock Books Blog, presented here by permission of the author. Pictures: Tavistock Books.