History Associazione Librai Antiquari d'Italia Pregliasco Libreria Antiquaria di Umberto Pregliasco

Living With - And From - Books, Part 5

A Century of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books of Literature, Fine Arts, Science and First Editions

By Umberto Pregliasco

Part 5

“A monk should surely love his books with humility, wishing their good and not the glory of his own curiosity; but what the temptation of adultery is for laymen and the yearning for riches is for secular ecclesiastics, the seduction of knowledge is for monks.”

(Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose)

A Bibliophile of Huge Ec(h)O!!

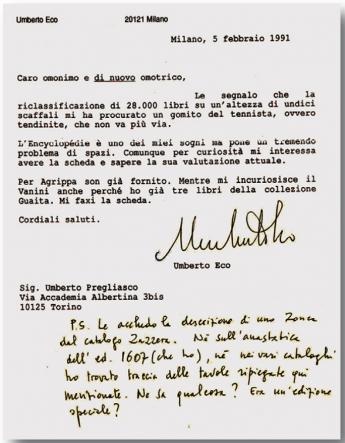

“Dear Omonimo ... let’s hope we never get rid of books” is the citation from a very fortunate article of ours on Umberto Eco. Among our famous clients at the “Libreria”, as a matter of fact, the author of The name of the rose shares many things with us: beside our “Piedmontesity” and the love for books, we also share the delight in playing with words and puzzles. Even the fact of having the same name has helped the relationship: we are jealously keeping the letters, still handwritten which he signed «Omonimamente Suo…», those in which he pointed out some inaccuracy in my catalogue, and even his complaints because a book he was looking for was already sold to others.

Sometimes I wonder which comes first in Eco’s novels, “the chicken or the egg”: we often ask ourselves if it’s the writer need which guides the book collection, or the possession of certain books which inspires the writing. One thing is for sure, all of his novels are supported by a deep study of antique texts as shown in Il nome della rosa with herbaria, texts on drugs, labyrinths and the Inquisition. The Name of the Rose is a biographical tribute to Jorge Luis Borges, represented in the novel and the film by the blind monk and librarian Jorge of Burgos. Borges, like Jorge, lived a celibate life consecrated to his passion for books, and also went blind in later life. Needless to say, my dream would be to find a manuscript of the lost second book of Aristotle’s Poetic, the one about laughing which causes Jorge’s homicides and the fire in the library - surely the source of the worst nightmares for any antiquarian bookseller. The same meticulous research on texts about alchemy and Rosicrucianism can be found in Foucault’s Pendulum, where three editors amuse themselves by inventing a conspiracy theory regarding the Knights Templar. For The Island of the Day Before, about a man in the Renaissance marooned on a ship within sight of an island which he believes is on the other side of the international dateline, Eco sought out books on the Jesuit order, navigation and astronomy. In this novel only the watchful eye of a bibliophile would notice that almost all the 40 chapters coincide with XVIIth century book titles.

Some are more famous such as the Grand’Arte della Luce e dell’Ombra by Kircher, the Serraglio degli Stupori by Garzoni, the Nautica rilucente by Pietro Rosa or L’Orologio oscillatorio by Huygens, others are less well-known such as Labirinto del mondo e paradiso del cuore, published in Czech by a Mr. Komeneski in 1631. In short, even the index is a downright hymn to bibliophily. Eco’s studies continued with books and texts about the siege of Casale, Crusades, Coniate and Barbarossa for the writing of Baudolino, a knight who saves the Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates during the sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade. Claiming to be an accomplished liar, he leaves the historian (and the reader) unsure of just how much of his story was a lie. He researched comics and magazines of the Thirties for The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, in which the protagonist is actually an antiquarian bookseller named Giambattista Bodoni, who emerges from a coma with only memories of the books of his childhood. Therefore, trough the years, Umberto Eco often came to Via Accademia Albertina looking for books on a great variety of subjects. A certain friendship began, sealed with mutual exchange of information – his knowledge of bibliography and the real importance of a book is exceptional – and I for one am certain that his intellectual contributions to ‘our world’ are infinitely more valuable than his commercial ones, however much money he spends! Anyway, we’ve never been able to guess the exact theme of the novels Eco was working on, but then as usual he would send us a copy of his latest work – recently we received The Cemetery of Prague –with the dedication: «so you’ll understand why I needed that book…».

A beggar's book out-worths a noble's blood.

(William Shakespeare)

One of Eco’s bibliophilic essays is titled The vegetal memory. The book on paper, vegetal record of human civilization, came after the first mineral record in cave paintings and the animal one in manuscripts written on vellum. I’m sure the printed book will be joined, but hopefully not supplanted, by the new record – mineral again – this time on silicon chips. Therefore, it is a great pleasure to publish some of the Eco’s confidences on collecting books:

“Of course there are bibliophiles who collect books on a subject and even read the books they are collecting. But, in order to read so many books, all you need to do is to become a bookworm. On the other hand, the bibliophile, even though he pays attention to the contents, he wants the object, and possibly the very first one that came out of the printer’s press. As far as this, I am stating that there are bibliophiles, who I do not approve, but I do understand, who - having received an uncut book – do not cut the pages in order not to violate the object they have conquered: cutting the pages of a rare book would be like, for a collector of watches, to break the case to check the mechanism.

“Naturally the bibliophile, also the one who collects contemporary books, is exposed to the dangers of the acquaintance that comes over, looks at all the bookcases and says: “How many books! Did you read all of them?” Our daily experiences tell us that this question is being asked also by those whose intellectual level is more than satisfactory. Facing this offence, I feel that there are three standard answers. The first one stops the visitor and cuts off any relationship, and it is: “I have not read any, otherwise why would I be keeping them here?” But this gratifies the annoying visitor, tickling his sense of superiority and I do not see why I should pay him this favor. The second answer has the annoying visitor plunge in a state of inferiority and sounds like: “Many more sir, many more!” The third is a variation of the second and I use it when I want the visitor to fall into a painful amazement. “No – I tell him – I keep the ones I already read at the University, these are the ones I must read by next week”. Since my library holds about fifty thousand volumes, the poor thing only tries to leave sooner, stating he has some sudden commitments.

What the unhappy person does not know is that the library is not only the place for your memory, where you keep what you have read, but the place for universal memory, where one day, in a fatal moment, you’ll be able to find what others have read before you. It is a repository, where at most everything melts and generates vertigo, a cocktail of erudite memory.

Never read any book that is not a year old.

(Ralph Waldo Emerson)

Personal Collections and Translations

Some booksellers are also collectors, and we are no exception: over the years, Arturo has put aside some particularly meaningful Italian books – from a variety of antique illustrated books to a complete collection of Leopardi’s first editions of which he is extremely jealous – and a good number of princeps of the Italian literature of the Sixteenth Century, in particularly beautiful editions. Umberto has gathered a good selection of the first classical texts in the Vulgar language and a great number of first translations of the masterpieces of the modern English and French literature: therefore taking into consideration a period of time that spans from Virgil to Kafka, going through St. Augustine and Cartesio and some examples of first foreign translated editions of significant Italian works (from Tasso to Manzoni in French and up to Pinocchio in Russian).

Up to now, we feel that the importance given to translations through the centuries has been overlooked: for the very first time a masterpiece could be read not only by a limited number of educated public, but also by the lower classes. We can say that a translation is a form of writing: such as a narration, an essay or poetry. Its history cannot be divided from the one of languages, of cultures and of political events: “Each civilization is born from a translation” Folena wrote, and as a matter of fact, the Latin literature has been taking shape from the translations from Greek, modern German owes a lot to the Lutheran translation of the Bible. Identifying which was the first translation of a masterpiece is not an easy task, since bibliographies are as scarce as they are incomplete.

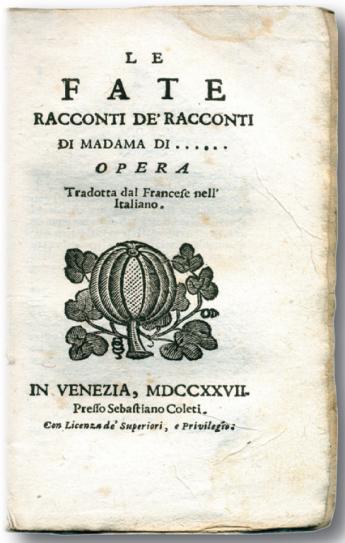

Their rarity often prevents to establish with certainty the name of the translator and even the date. To this purpose, we would like to remind that a few years ago, from a purchase of simple children’s books, a small octavo volume popped up, the binding was in a poor cardboard and the frontispiece without the name of the author or the translator, bore the title: “Tales of Fairies. Translated from French into Italian / In Venice, MDCCXXVII, published by Sebastiano Coleti”. Its discovery has revolutionized the history of translations of Perrault’s masterpiece, “Histoires ou Contes du temps passé”, published in 1697. Rouger’s bibliography (1967) points out as a first translation in the world the English one of 1729, while it identifies A. Mercurio’s translation of 1752 as the first Italian one. Therefore, this one, dated 1727 not only is the true first translation into the Italian language, but even, rare event in the literature of our country, the very first one in any language. If we are allowed to use this paradox, this is a kind of proof of Kant’s theory of knowledge: “it is not the existence to determine the knowledge” of something, but “the knowledge determines its existence”: a given rare book comes to exist only at the moment when a book dealer finds it and makes the bibliographic discovery available to the public. Apparently, no other copy of this edition is kept in Italian or French libraries, due to the extreme wear of a book handed to children. So one more fragment has been added to the history of this editorial Cinderella that, discovery after discovery, starts looking like a princess. Emblematic of the naivety of the translator is The Little Chicken, that became famous in the modern times as Little Thumbing. The translation into “little rooster” originated by an orthographic error occurred to the anonymous translator, who misunderstood the term Poucet (Thumb) for Poulet (Chicken).

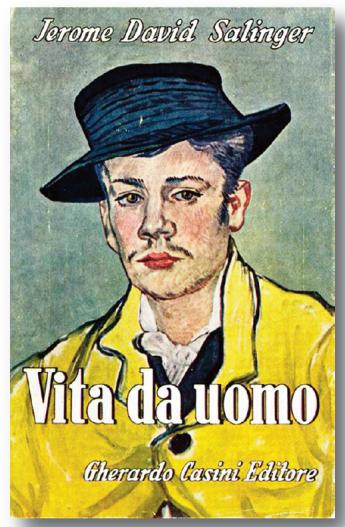

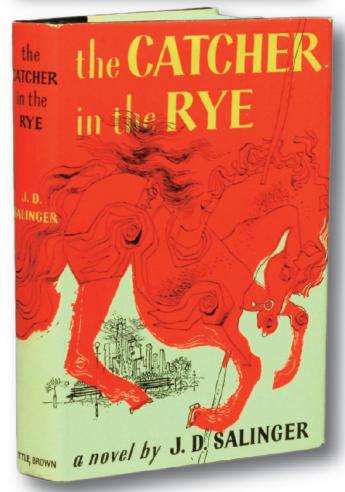

The study of this collection of translations – which in a few years will become a new monographic catalogue – will also allow to place our attention to the translators, often obscure, but sometimes famous writers, like those who introduced us to the contemporary American Literature, such as Fernanda Pivano for Lee Masters, Fitzgerald and Hemingway or Cesare Pavese with Melville, but also with Walt Disney. If it is stated that in 1932 Pavese published in Turin the first translation of Moby Dick, almost unknown is that the year after Franco Antonicelli, at the same publisher, was responsible for the very first appearance of Mickey Mouse (Storielle e illustrazioni dello Studio di Walter Disney, n. 1). It should be noticed that, due to the lightheartedness of this comic strips, Pavese did not want his name to appear, while Antonicelli signed with the pseudonym of “Antony”. It shall also be possible to highlight some editorial curiosities (for example, the very first Spanish translation of Pinocchio saw the light in Bogotà, and not in Spain, the very first French version of Giacomo Leopardi’s Poetry was in prose) or some title modifications such as in the case of Salinger: the first version in Italian of The catcher in the rye is the one by Jacopo Darca of 1952, titled Vita da Uomo (An adult’s life). Only nine years later with Adriana Motta’s translation and the new title Young Holden it did meet the right consideration. The only version of its untranslatable English title, which may be applied to the Italian passion for soccer, could have been “The full back into grappa”, that is the role that Holden feels he needs to take to defend young kids from a society where he cannot identify himself.

To be continued ...

Part 5 of "Living With - And From - Books: A Century of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books of Literature, Fine Arts, Science and First Editions", published by Umberto Pregliasco on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco. The text is presented here by permission of the author.

>>> Read the whole story

>>> Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco