History Associazione Librai Antiquari d'Italia Pregliasco Libreria Antiquaria di Umberto Pregliasco

Living With - And From - Books, Part 4

A Century of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books of Literature, Fine Arts, Science and First Editions

By Umberto Pregliasco

Part 4

Where one begins by burning books, one will end up burning people.

(Heinrich Heine)

The 20th Century

When One century of literature for the New Italy 1860-1960 was conceived, Arturo was among the firsts in Italy to put the emphasis on the literature of the Twentieth Century: no. 16, published just in 1960, was later followed by the two Italian Literature in the 20th Century (no. 52 of 1985 and no. 73 of 1996). For the first time, in the Sixties, contemporary literature and Futurism were acquiring a bibliographic dignity and were starting to assume an appraisal that was adequate for their importance, getting closer to the original editions in English and in French. Naturally, the prices were still those of a second hand book, if we think that the Canti orfici by Dino Campana, offered in 1960 at 18,000 Lira, are now being offered, uncensored and uncut for 10,000 Euro; and the Leopard, sold in 1985 for 90,000 Lira, appears now for 2,500 Euro, but it has also been sold at foreign auctions for twice the amount, thanks to the international success of the movie version by Luchino Visconti. Many of the items ended up in Japanese institutions and almost half was addressed towards Yale University, as a testimonial to the opening of these foreign libraries to new literary cultures. The criteria for collecting first editions by now have been further refined, giving a great importance to the state of preservation, to the dust jackets and even to the wrappers and the sticker bearing the price.

The Discoveries of the Book Dealer

The role of the rare book dealer is not limited to purchasing and selling: his attention is not confined to the wholeness of a copy, its preservation, and the beauty of its cover. The charm of a book lies, besides in the text, in its publishing adventures, and in the changes of ownership that it has lived through the centuries. The curiosity in intensifying its study at times brings the antiquarian to notice some details that up to now had been ignored, leading him to some true bibliographic, historical and literary discoveries.

Tommaseo, Manzoni’s editor: In 1998 the auction for the library belonging to the famous Giannalisa Feltrinelli was held at Christie’s, over four turns. There were many important pieces that the catalogues were highlighting. In the last session, in the secondary location in South Kensington, among the pieces presented there was a copy with notes of the not so rare first edition of the Promessi Sposi. After a more careful exam, we realized that the notes were by Niccolò Tommaseo. Traces of this exceptional item had been lost for more than a century, and we were very excited to be able to purchase it to take it back to Italy. In 1827, Tommaseo was about to leave for Dalmatia, but unfavourable weather forced him to remain for days on a ship in the port of Ancona. Manzoni had just given him one of the very first copies of his novel as a gift, published with the date 1825-26, but released by Ferrario in June of 1827. He took advance of this forced staying to write notes with his minute writing over more than one thousand pages of the volumes, from a couple of lines per page, up to long comments in the lower margins at the end of the chapters. When he returned to Florence, he published the article on the Viesseux’s Anthology and he gave the novel to Gino Capponi’s daughter as a gift; in 1887, Bencini transcribed the annotations at the National Library of Florence and from that time, nobody knew anything anymore of the three volumes. Therefore, we properly studied them, publishing a long description at the end of the first part of the catalogue on Lombardy (no. 77). That great character who was Giancarlo Vigorelli, president of the Centre for the Studies on Alessandro Manzoni, immediately found the money to purchase it, planning a facsimile within the national edition of his works, that will be published in 2012.

Among hundreds of annotations, we are reminding: “it is the Seventeenth Century manners proper to the people of Milano – Eroica is self-consciou s– it seems to be an awkward dialogue by Goldoni – I do not like it” (referred to the statement by the Prince of Condé). Or exclamations of approval such as “Divine! Sublime” (about the “the unlucky one answered” of the Nun of Monza). The voice latinorum of Azzeccagarbugli is defined as “heavy” by Tommaseo, who – about one of the most beautiful pages of Italian literature (“Adieu mountains rising from the water and erecting towards the sky” was written in the first edition) – sternly commented: “Erected is clumsiness”, inducing Manzoni to reach the utmost “Adieu mountains… elevated to the sky” of the final text of 1840.

These annotations were fundamental to induce Manzoni to “rinsing clothing into the Arno”, through which he got rid of typical expressions of the Seventeenth Century and of those typical of the dialect of Lombardy. And so it was on board of a ship anchored in the port of Ancona that this relevant episode in the history of the Italian language took place; it was a great reason for pride for us, as booksellers, to have contributed to the care of the volume and to the rebuilding of this meaningful feature of the literary history of our country.

Everything in the world exists in order to end up as a book.

(Stéphane Mallarmé)

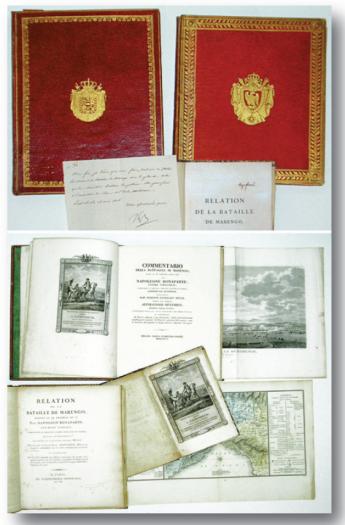

When Foscolo did not want to write for Napoleon

On the other hand the Sotheby’s in Paris was the theatre for another discovery: in December of 2006 the part of the Provenances Imperiales of the Temple de Rougemont library was put on sale. We immediately noticed the copy that had belonged to Napoleon of the Relation de la Bataille de Marengo, with a red morocco binding bearing the arms of Napoleon, along with the autographed letter of the Emperor ordering Eugène de Beauharnais to provide the Italian version. And the Emperor’s copy in morocco binding of such translation by anonymous, of which only five copies are known to exist. The minister of War Caffarelli had sent to nobody other than to Ugo Foscolo the French economical version to work on the text. The poet was composing “i Sepolcri” and Pindemonte sent him a booklet on the subject to help him out, and on the French copy Foscolo marked the translation of a few words in pen. These two small volumes with Foscolo’s annotations both come from the same source: Cortland F. Bishop and Boddington, but their modest cover was not appreciated by the Rougemonts who passed them on to Guy Tosi, among the greatest French scholars of Italian. The key was to get together this group of items, made unique by the two sumptuous bindings, by Napoleon’s letter and by the hand written annotations by Foscolo, opening a small new window on the Italian literature of the Nineteenth Century. Chiara Clemente’s meticulous study appeared at the beginning of Catalogue 95 and it ended with a charming note on the “poulet à la Marengo” cooked after the battle by chef Dunand with the ingredients that had been scrambled from the farmers.

Once again, Foscolo, in love this time

In 1989, at a small American auction company, a collection of books with “fore-edge-paintings” was auctioned. This decoration is typically Anglo-Saxon and it refers to a painting on the edges of the pages of a book such that it is not visible when the book is closed: the leaves must be fanned, exposing the edges of the pages and thereby the painting. Among many English texts, we noticed a copy of Essays on Petrarch by Foscolo, who held these lectures at Sir Henry Russel’s home during his London exile. Besides the ordinary edition, in 1821, there was a special printing of only 16 copies, dedicated to the members of the Russel family.

For mere curiosity, we asked one of our best American colleagues – and friends – Jonathan Hill to view the copy: it was no. II, for the daughter, Caroline Russel, and we asked him to buy it, at any price. When we received the volume, in brown leather with rich golden designs and a refined view of Venice painted on the vertical edge, we were already quite satisfied, but more surprises were still to come. After evenings spent researching – the internet was not existing yet – we discovered that only in two of the copies, the one he kept for himself and the one destined to his beloved Caroline, he dared adding, between pages 164 and 165 the Ode To Callirhoe. It is the only example of English verses written by Foscolo, and having them printed in only two copies: “maybe he never loved any other woman as much as Miss Russel; of course he has not suffered for any other woman as much as he suffered for her … only in the copy destined to Caroline and in the one for himself he put the Ode to Callirhoe” (Chiarini page 382).

Lord Russel had sent his daughter far away from the wild poet, who then sent this volume to the Florentine historian Gino Capponi so that he could deliver it in Lausanne: “Having heard that his friend was about to visit Switzerland, he sent him a package and a letter to deliver to Miss Russel … it contained one of the 16 copies of the luxury edition (non for sale) for which he wrote a particular dedication to Calliroe, with some English verses printed by him and addressed only to her. These are the only English verses that are known”. This “bibliographic ghost”, hidden during the last 150 years in an ordinary library somewhere in the US, deserved a beautiful description in Catalogue no. 60, produced in cooperation with our great Parisian friends Bernard and Stéphane Clavreuil of Librairie Thomas-Scheler.

“Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people, citizens of distant epochs, who never knew each other. Books break the shackles of time, proof that humans can work magic.”

(Carl Sagan)

Not only Books. Engravings and “Oddities”

Among the volumes that bind the one hundred years of the bibliographic repertoire of our Libreria, taking the space of up to two whole bookshelves, peep out also some small and big collections of engravings by maestros, drawings, miniatures, water colour paintings and gouaches. Among these we are reminding the Maestros of Graphic Arts, Nonsologuaches, up to Gothic-Renaissance Miniatures, an elegant pamphlet produced by Allemandi in 1984: “As it is known, Federico di Montefeltro was very proud of his own library, where all the books were ‘written in pen and there was none of them that had been printed’. Collecting manuscripts has always been an activity that for bibliophiles is just as time consuming as it is rewarding, that goes with the difficulty in finding the so longed for manuscripts and the gratification to own objects that are unique, not part of a series, illustrated manuscripts or autographs.”

Expression of a certain love for rediscovering the unusual was, for example, in 1991, Manet (et manebit), that will be remembered through time since he placed the accent on the little known activity of Edouard Manet as an engraver and presented thirty original etchings, realized between 1862 and 1868, mainly kept as artist’s proofs, destined to friends or collaborators. The album printed in bistre, just like the engravings, was accompanied by a huge critical work, that up to now was unpublished in Italian: “Manet the engraver, replaces the brightness and the colours of the impressionism with tone contrast, the knowledgeable placement of spots of light, the discontinuity of the tracts; he breaks the classical perspective and tries to project his subjects forward to make the spectator’s feelings more immediate”.

In 1988 it was the time for another Master Painter, Marc Chagall, with one of his hand painted 85 series, of his 100 etchings produced to illustrate La Fontaine realized in 1930, but unknown until 1952: “The coloring was made by Chagall with icastic paint brushes with lively and surreal colors that stand out from the accentuated light and shade effects, highlighting some of the narrative elements. The fact that Vollard wanted one of the masterpieces of French literature to be illustrated by a Russian origin artist was quite criticized in the Parisian society; but what Chagall is about to interpret, is not the work of La Fontaine in its temporal ties with the classical French era, but the eternal and the universal content of tales” (from the introduction by G. L. Marini).

Yet more unusual are the recent Oddities of various figures, the fancies of a Seventeenth Century surrealist, which, on the other hand, celebrates one of the less known Italian engravers, but amazing forerunner of the artistic movements of the 20th Century, from Surrealism to Cubism: Gianbattista Bracelli. Only two complete series of the 50 tables (Paris and Washington) are known, and three other incomplete ones, but none of them in Italy. The elegant square album, written in English and in Italian by Chiara Tirabasso, reproduces this series of visual strangeness almost in its whole entirety, “playful images and changes of the human shapes, transfigured into an oneiric choice of animated and inanimate human components” such as drawers, racquets, tennis balls, geometrical shapes, kitchen tools. “Tzara rediscovers Bracelli, and, becoming the touched interlocutor of his language, removes him from centuries of unjust oblivion and places him on the pedestal of the forerunner fathers of surrealism ... Madness, unbridled imagination are contained and organized thanks to the shape, the care in the contours and the drawing, on how the foreshortenings are rendered”. (Anna Mariani).

Books have led some to learning and others to madness, when they swallow more than they can digest.

(Petrarch)

Honoring Some Great Italians

Besides the already mentioned literature catalogues, we could not skip honouring some of the milestones of our literary history. The catalogue dedicated to Alessandro Manzoni (no. 36, 1973), in the one hundredth anniversary of his death, was presenting over 500 items, including editions of the Promessi Sposi, prose, poetical works, letters, critics, but also prints inspired by his Novel. Not less noticeable were Pascoli and Carducci (no. 34, 1972), protagonists of a huge repertoire that included first editions and reprints, anthologies and introductions written by them, besides volumes of critical essays on Pascoli’s and Carducci’s work. “In the literary history of the great century that ran throughout Italy from 1750 to 1850, when it will be written with objective serenity and without any political party related worry, Vincenzo Monti will once again have the place he deserves, as prince of Art... as a reviver of the classical feeling in its best expression”. With this prophetic citation by Carducci the catalogue dedicated to Vincenzo Monti (no. 64, 1992) ends; it consisted of 295 items of the vast literary and poetical production of the poet and playwright: autographs, tragedies, chants and poems, translations, prose and autographs of family members, biographies and critical works. “Rediscovering a poet that, although accused of political opportunism and moral contradictions, in Italy and in Europe was able to conquer a place of undeniable prominence” was a very true bibliographic endeavor, since there was no complete critical edition of Monti’s works and the preparation of this monograph was quite difficult, so that the afterword conclude this way: “The bibliophiles shall judge whether we did a job that was not useless”.

At last, we would like to remember with affection and not only literary, but personal, catalogue no. 17, Benedetto Croce, printed in 1966 for the hundredth anniversary of his birth and containing over 700 items, which also included works edited by or with introductions by Croce, besides the Laterza series promoted or directed by him. When this monograph was published, Croce had been deceased for only eight years, therefore this was a very unusual catalogue produced by an antiquarian bookshop, since it is dedicated to a contemporary author. “While putting this catalogue together, several times, we felt we might be hearing his warm voice, as when, in our bookshop, he used to chat with one or more of his friends who often came along with him”, the afterword states. Moreover, the edition of the correspondence that was for sale, already contained a few letters sent by the philosopher to Lorenzo Pregliasco, or to others with references to the “Libreria”, as in one dated September 1935:

“I’ll come to Torino the day after tomorrow (Thursday), and I’ll go to the library immediately. In the afternoon I’ll go and see Pregliasco...”.

To be continued ...

Part 4 of "Living With - And From - Books: A Century of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books of Literature, Fine Arts, Science and First Editions", published by Umberto Pregliasco on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco. The text is presented here by permission of the author.

>>> Part 1

>>> Part 2

>>> Part 3

>>> Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco