Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Adrian Harrington Rare Books

Collecting â Arthur Conan Doyle: Social Justice Warrior

By James Murray

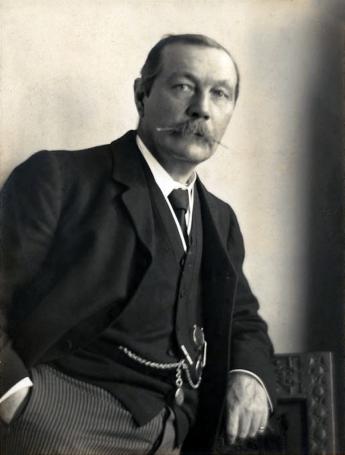

Arthur Conan Doyle was hardly a meek man, nor one prone to seeking diplomatic solutions when dramatic alternatives were available. When he attempted to enlist in the military forces he wrote that “I am fifty-five but I am very strong and hardy, and can make my voice audible at great distances, which is useful at drill.” This audible voice proved to be very significant for two individuals in particular; George Edalji and Oscar Slater. My interest in these two men was sparked by our recent celebration of “Arthur Conan Doyle Week” at the end of May in honour of his birthday. Fortunately or otherwise, the Olympia bookfair has prevented me from typing up some of the more fascinating aspects of Doyle’s life that I discovered during that week.

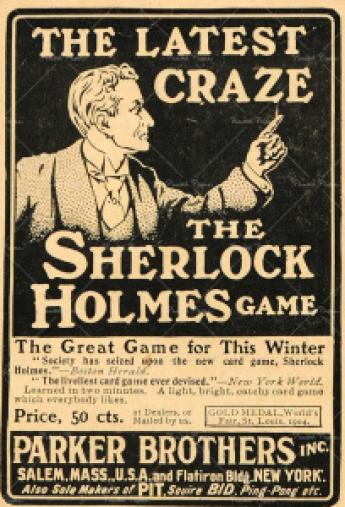

Recently novelised by Julian Barnes as Arthur and George and then adapted as a television drama of the same name, the story of Arthur Conan Doyle’s real-life detective work has fired innumerable imaginations, and further blurred the line between the author and the world’s most famous consulting detective, Sherlock Holmes. Doyle is most famous for his privately-conducted PR campaign on two cases: the first, that of astigmatic and myopic solicitor George Edalji, accused of savaging a pit pony and conducting a poison pen letter campaign against his own family; and the second, that of Oscar Slater, in which a German Jewish immigrant was falsely accused of murdering an 83 year old spinster during a botched robbery before fleeing to the United States. In each case, there was significant evidence that a combination of police incompetence and police corruption had given rise to the charges, and Doyle was instrumental in uncovering and then proving that this was the case.

The case against Edalji ran as follows. When George was twelve, a series of threatening letters were sent to his father, the vicar Shapurji Edalji. These events, in which George was considered a possible suspect despite being a child, culminated in the firing and conviction of the Edalji’s maid-of-all-work. A second wave of poison pen letters arrived four years later, in which Shapurji was accused of, amongst other things, “gross immorality with persons using Vaseline in the same way as did Oscar Wilde”. This campaign also subsided, though public opinion in the village of Great Wyrley, where the Edaljis lived, had begun to favour either the Shapurji or George as the culprits. This view was also taken up by Police Constable Upton, who Shapurji had earlier praised for his investigation into the first poison pen letter case, and expressed by Chief Constable of the county, Captain Anson. It seems clear that Anson had decided this primarily on racist grounds, and his views may have put pressure on those beneath him to adopt similar views. In 1903 there were a series of animal maimings, and investigation of these rapidly turned to George, although there was slim evidence that he was involved. When Doyle became involved with the case, after Edalji had served three years in jail and then been paroled, the chief evidence that he thought established George’s innocence was his eyesight. The maimings had occurred at night, and required physical strength and manual dexterity – in turn dependent on visual acuity. George’s eyesight was so poor that he had to hold a newspaper inches from his face in order to see it clearly. On the basis of his medical training in ophthalmology, Doyle thought it impossible for George Edalji to have been responsible for the maimings. This evidence had been available to Edalji’s defense team, but they thought it obvious that the prosecution’s case was a farce that would be thrown out and made no mention of it during proceedings.

As a direct result of Doyle’s public campaign into the circumstances of Edalji’s arrest and trial, the Home Office conducted a parliamentary review. That review found that the evidence provided to establish Edalji’s guilt, compounded by the fact that the police sought only evidence to incriminate Edalji rather than evidence pertinent to the case, made the conviction unsafe, and recommended that the Home Secretary overturn his conviction, in spite of the recently passed guidelines concerning the issuing of pardons. However, the jury and the magistrates leading the enquiry both felt that Edalji was likely to have brought the trouble upon himself by conducting the poison pen letter campaign, which, from a modern perspective also looks to be a false accusation. As a direct result of this, while the Home Secretary restored Edalji’s professional standing and issued a royal pardon proclaiming his innocence, he refused to compensate him for his three years of imprisonment.

By contrast, Oscar Slater was a known pimp and a gangster, very much one of the usual suspects. During a ten minute window of opportunity when the maid of 83 year old Marion Gilchrist left her mistress on her own in the house, Gilchrist was beaten to death and one of her brooches was stolen. The evidence implicating Slater was slim, to say the least. A person had called at Gilchrist’s house several days before looking for “Anderson”, one of Slater’s previous aliases; someone reported seeing Slater trying to sell a pawn ticket; and Slater had left the country five days after the murder.

When informed that the Scottish police were seeking his extradition, Slater returned voluntarily from the US. During his trial, an alibi was provided for his whereabouts at the time of the murder, and further evidence was provided establishing his plans to travel to the United States had been made long before his alleged flight. Regardless, the jury voted to convict 9-5, and he was sentenced to death, which was later commuted to life imprisonment as a result of public outcry.

Persuaded by research conducted by William Roughead, Doyle wrote passionately in defense of Slater. Two years later, in 1914, a private enquiry was held, during which evidence provided by one of the original detectives on the case that showed Slater to be innocent was disregarded, and John Thompson Trench, the detective in question, was dismissed from the force. It would be another 14 years before Slater was pardoned in 1928.

***

Published on Adrian Harrington Books. A Literary Scellany, presented here by permission of the author and Adrian Harrington. Pictures: Adrian Harrington Rare Books, Wikipedia