Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Simon Beattie Ltd

Banned Books Week - All that Hell could vomit forth

By Simon Beattie

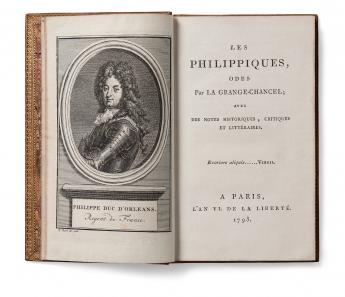

This week is Banned Books Week. I’ve written about banned books before: the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, in the Weimar Republic, in the Soviet Union. Here’s something a little earlier: the libellous Philippiques of François-Joseph de Lagrange-Chancel (1677–1758). These virulent satires against the Regent, the duc d’Orléans, enjoyed a huge popularity in manuscript throughout the eighteenth century, as the varied examples here show. ‘In spite of its imperfections and crying injustice, it is the monument of satire in France’ (Nouvelle biographie générale).

Lagrange-Chancel was initially known for a number of tragedies on Greek themes published from the mid 1690s onwards, which had gained him the attention of Racine and won him favour at court. But everything changed when, around 1720, three odes under the title ‘Philippiques’ began to circulate suggesting the Regent committed incest with his daughter, the Duchess of Berry, and that he desired the death of the young Louis XV. Saint-Simon records the events: ‘About this time appeared some verses under the title of Philippiques, which were distributed with extraordinary promptitude and abundance. La Grange, formerly page of Madame la Princesse de Conti, was the author, and did not deny it. All that Hell could vomit forth, true and false, was expressed in the most beautiful verses, most poetic in style, and with all the art and talent imaginable. M. le Duc d’Orleans knew it, wished to see the poem, but could not succeed in getting it, for no one dared show it to him.

‘He spoke of it several times to me, and just demanded with such earnestness that I should bring it to him, that I could not refuse. I brought it to him accordingly, but read it to him I declared I never would. He took it, therefore, and read it in a low tone … He judged it in reading much as it was, for he stopped from time to time to speak to me, and without appearing much moved. But all on a sudden I saw him change countenance, and turn towards me, tears in his eyes, and himself ready to drop …

‘He was at the part where the scoundrel shows M. le Duc d’Orleans having the design to poison the King, and quite ready to execute his crime. It is the part where the author redoubles his energy, his poetry, his invocations, his terrible and startling beauties, his invectives, his hideous pictures, his touching portraits of the youth and innocence of the King … in a word, all that is most delicate, most tender, stringent, and blackest, most pompous, and most moving, is there’ (Memoirs of the Duke of Saint Simon, IV, 130–2).

Lagrange-Chancel fled to Avignon, but was arrested and sent to the Ile Sainte-Marguerite, only to escape to Sardinia, then Spain and Holland, where he produced the fourth and fifth odes. He returned to France after the Regent’s death in 1723 and his book, which had first appeared in manuscript, fascinatingly continued to do so right through the century.

On the background, see Adolphe de Lescure, Les Philippiques de La Grange-Chancel, nouvelle édition … précédée de Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de La Grange-Chancel et de son temps … (Paris, 1858).

(Posted on The Books You Never Know You Wanted, presented here by permission of the author.)