Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Simon Beattie Ltd

âI never have any luck with my booksâ â Collecting the works of Friedo Lampe

By Simon Beattie

Friedo Lampe. Am Rande der Nacht. For me, name and title evoked those lighted windows from which you cannot tear your gaze. You are convinced that, behind them, somebody whom you have forgotten has been awaiting your return for years, or else that there is no longer anybody there. Only a lamp, left burning in the empty room. (Patrick Modiano, The Search Warrant)

On 2 May 1945, in Kleinmachnow, just outside Berlin, two Red Army soldiers stopped a passer-by, and demanded his papers. The man - tall, thin, but broad-shouldered, in a dark blue coat, hat, and with a rucksack on his back - did as he was asked. But something was not right. The Russians began to question the man, who did not quite resemble the photograph before them. Five minutes later, having not been able to make himself intelligible to the soldiers, the man was ordered onto a nearby patch of grass. He raised his arm across his face, when two shots were fired, and he fell to the ground.

We might dismiss the incident, over seventy years later, as a tragic circumstance of war, a case of someone being in the wrong place at the wrong time, but for the fact that we know exactly who that man was. His name was Friedo Lampe, he was 45 years old, and he was a writer. As a gay man in Germany during the Third Reich his life could have ended much sooner, but he had survived. Yet, gnawed with worry at the possibility of being found out, and fearing for friends who were called up to fight, he had lost a great deal of weight during the War, so much so that he no longer resembled the photograph on his identity card. He had almost survived: the War itself ended only six days later, on 8 May.

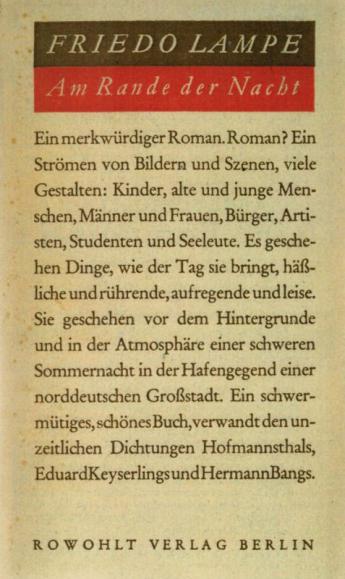

It was in Hamburg that he became acquainted with young writers such as Wilhelm Emanuel Süskind (father of Patrick) and Joachim Maass, who wrote for the avant-garde monthly arts magazine, Der Kreis. The Nazis’ seizure of power in January 1933 soon put paid to the magazine, which was shut down months later. Many of Lampe’s writer friends went into exile. But Lampe himself was writing, and his first novel, Am Rande der Nacht (‘At the Edge of the Night’), was published by Rowohlt in Berlin at the end of October 1933. The Oxford Companion to German Literature tells us that it ‘evokes the sensations and impressions of a September evening in Bremen with its charm and tenderness, its squalor and its lust, held together by the thread of the melodies of Bach …’. But there is more to it than that. The title-page of the novel is dated 1934, but by then the book was already unavailable: in December 1933 it was seized by the Nazis, withdrawn from sale, and later included on their official ‘list of damaging and undesirable writings’ due to homoerotic content and its depiction of an interracial liaison between a black man and a German woman. Lampe wrote at the time that the book was born into a regime where it could not breathe, but hoped that one day it might rise again.

Lampe loved Ancient Greek literature; his later heroes were Kleist, Otto Ludwig, and Cervantes. But it was his keen interest in the cinema which influenced his first book most. Lampe conceived the novel as filmartig (‘film-like’, ‘cinematic’) when he was writing it, intending ‘everything [to be] light and flowing, only loosely connected, graphic, lyrical, strongly atmospheric’. The result is a narrative style which moves from long streams of comma-separated clauses of reported action, almost like stage directions, to passages of fluid, sensuous lyricism. There are frequent changes of voice, and regionalisms mix with more poetic language. Writing in 1959, Heinz Piontek called Lampe ‘one of the first German writers to transfer the technology of film onto prose. His eye has something of a camera about it, dissecting the action into “sequences”’; the editors of Rowohlt’s 1986 collected edition drew attention to Lampe’s ‘soft cross-fades, clean cuts or deftly executed pan shots’. As Lampe wrote in Laterna magica, a short story published only after his death: ‘The most important thing is the cut.’

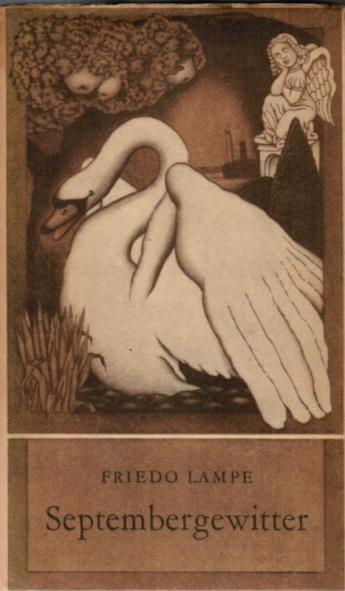

Nazi censorship policies also made things difficult for Lampe as a book-buying librarian, and in 1937 he moved to Berlin, where he accepted a job as an editor with Rowohlt. Lampe’s second novel, Septembergewitter(‘September Storm’), came out in December that year. Despite positive reception from critics, sales were poor, in part due to bad timing: it was too close to Christmas, and by the January the new book was old news.

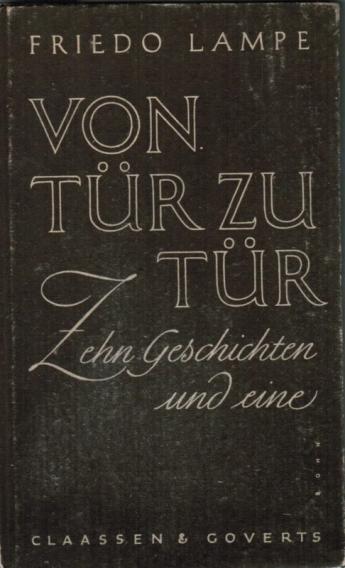

A new edition of Septembergewitter (printed in a collection of short stories entitled Von Tür zu Tür, ‘From Door to Door’, in which any English names in the novel were replaced with Danish ones) was planned for 1944, but it was beset with problems: the threat of closure for Goverts Verlag, a lack of paper for printing. Finally, paper was secured, and the type set, only for most of the edition to go up in flames during an air raid on Leipzig. ‘I never have any luck with my books,’ Lampe commented.

After the destruction of his flat, Lampe had moved to Kleinmachnow, between Berlin and Potsdam, where he was given refuge by the writer, Ilse Molzahn, whom he had got to know when working at Rowohlt. She had left the city for the relative safety of Silesia, and was only too pleased to know someone would be living in her house. Lampe found living there an ‘idyll’ after the horrors of Berlin. By the end of 1944, Lampe had been drafted into working for a branch of the Nazi Foreign Office, editing reports from intercepted enemy news broadcasts. As the months went by, Lampe understood all too clearly the course the War was taking, the regime’s impending defeat, and the nature of its crimes. Lampe called the work ‘gruelling, a real grind. Six hours of tense, eye-straining correction work a day, lots of night shifts, constant tiredness … But I am lucky with how things are. I was examined again recently and marked down as “out of commission”’.

Lampe’s body was taken to a local Catholic priest, and later interred in a nearby cemetery. His grave is marked by a simple wooden cross, carved with the words ‘Du bist nicht einsam’: ‘You are not alone’.

Hermann Hesse later wrote: ‘His novel Am Rande der Nacht appeared in 1933. I read it at the time with great interest, as German prose writers of such quality were rare even then … And what struck us at the time … as so beautiful and powerful has not paled, it has withstood; it proves itself with the best, and captivates and delights just as then.’

Von Tür zur Tür was republished in 1946; a new version of Am Rande der Nacht, with the ‘offensive’ passages removed, appeared in 1949 as Ratten und Schwäne (‘Rats and Swans’). A volume of collected works was published in 1955 (in which, likewise, Am Rande der Nacht appeared in an expurgated version); an enlarged, second edition came out in 1986. A new edition of Am Rande der Nacht, following the text of the first edition, was published in 1999, to mark the centenary of the author’s birth. Lampe’s work has been translated into French, Dutch, and Italian. According to Wikipedia, translations into Serbian and Spanish are to follow, but none of his work has ever appeared in English.

***

Published on Simon Beattie’s blog The Books You Never Know You Wanted and in The Book Collector, Summer 2016. Pictures: the author.