Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Ten Pound Island Book Company

To Google Or Not To Google? - Arachnophobia

By Greg Gibson

My sister-in-law and I have always enjoyed arguing. Not about big stuff, you understand. Just petty, nit-picky arguments to liven up the sleepy time following one of her terrific Saturday dinners. Is North Dakota a blue or a red state? Does a hurricane spin clockwise or counterclockwise? That sort of thing. With no solid factual basis for an answer at hand, you’ve got to rely on your wits to defend your position. It’s excellent exercise after a big meal, sort of like taking a walk.

Then, a few years ago, she got a smart phone. We’d be in the midst of one of our typical jousts, waiting for the pie to warm up, and she’d pull out her device and Google the answer. This was not an improvement. Arguments were resolved instantly, and we’d be left staring dumbly at our empty plates. Soon, by mutual and unspoken agreement, the smart phone disappeared from the dinner table. Our arguments resumed in their fuller and more satisfying configuration.

This recollection leads me to wonder what I ever did – when I absolutely had to know something – before Google? That godly search engine and its equally marvelous repository of information, Wikipedia, have become so pervasive in our lives it’s hard to remember what the world was like without them.

But if I think about it really hard (this is precisely the sort of answer I cannot Google), long shelves of encyclopedias come to mind. The Americana and the Colliers sets of my youth were sources of lots of cool info, like how to make gunpowder, but they were woefully short on facts about girls and sex.

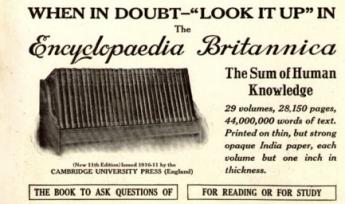

Later, having discovered that girls were the best source of knowledge about girls and sex, I graduated to the Encyclopedia Britannica, eleventh edition, as the go-to source for information about almost anything else that was in the world prior to World War I. I’ve still got my set, modestly bound in cloth, with its India paper pages and teeny type, and I still rely on it when cataloging rare books.

For example...

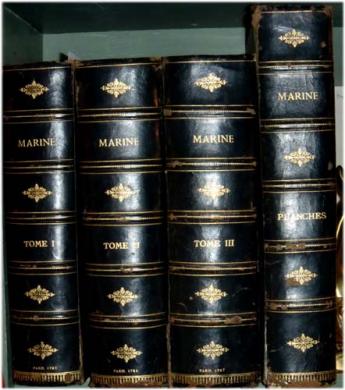

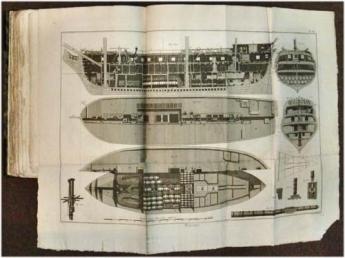

I’ve just acquired a handsome set of four books (three fat text volumes and an atlas of plates). Published in Paris in 1783-87, it is an alphabetically arranged compendium of knowledge about ships, shipbuilding, sailing, navigation, naval matters, and all aspects of marine technology. It was edited by a man named Pancoucke and, according to the information printed on the half title, this set – “Marine” - it is just a small part of

L'Encyclopédie méthodique ou par ordre de matières par une société de gens de lettres, de savants et d'artistes; précédée d'un vocabulaire universel, servant de table pour tout l'ouvrage, ornée des portraits de MM. Diderot et d'Alembert, premiers éditeurs de l'Encyclopédie.

Or, as Google Translate would have it,

“Methodical Encyclopedia or order materials by a society of men of letters, scholars and artists, preceded by a universal vocabulary for table for all the work, adorned with portraits of MM. Diderot and d'Alembert, the first editors of the Encyclopaedia.”

So, seeking information, I Google "Diderot" and get some pictures, a map, and a few thousand words in Wikipedia that read like a high school history text. Factual and useful enough, but boring.

By contrast the “Diderot” article in my Encyclopedia Britannica is replete with gems like, “he vexed his father’s brave and worthy heart by turning away from respectable callings like law or medicine, and throwing himself into the vagabond life of a bookseller’s hack in Paris. An imprudent marriage (1743) did not better his position. His wife… was a devout Catholic, but her piety did not restrain a narrow and fretful temper, and Diderot’s domestic life was irregular and unhappy. He sought consolation for chagrins at home in attachments abroad…”

Diderot, while seeking consolation abroad, also set out to translate an English encyclopedia for a French bookseller. “[B]ut in his busy and pregnant intelligence, the scheme became transformed.” The project stretched out over twenty years, from 1745 to 1765. Ultimately his Encyclopedie consisted of twenty-seven folio volumes. “He wore out his eyesight in correcting proofs and he wearied his soul in bringing the manuscript of less competent contributors into decent shape.”

The Britannica article then referred me to another article on encyclopedias. There, I learned that Charles Pancoucke undertook a new and enlarged edition of Diderot’s work in 1780. This effort, “arranged as a system of separate dictionaries” (of which my four volume Marine is one) took fifty years to complete, and ran in excess of 200 volumes.

Both Diderot and Pancouke were driven by the dream, conceit, fantasy, romance, or vision – for it was all of these things – that human knowledge could be categorized, collected, and made available to people who possessed the right technology – in this case a subscription to the Encyclopedie (each version had more than 4000 subscribers) and the ability to read it.

As time wore on we lost the charming certainty of Enlightenment thinkers that all knowledge could be recorded. With modernity came chaos – a deluge of information that cast the very idea of knowledge into doubt. Just Google “incompleteness theorem”, if you don’t believe me.

But now, in a way, Google has brought new life to that fantasy, that romance. Everything we know will be categorized and collected. Google spiders will crawl through it all, at the speed of light, and bring back the information we need.

Useful, but creepy. And will it ever yield phrases like, “vagabond life of a bookseller’s hack in Paris?”

Pancoucke, Charles (editor). ENCYCLOPÉDIE MÉTHODIQUE. MARINE.

Paries. 1783; 1786; 1787. b/w engraved plates, many double page or folding. Three 4to volumes. xii, (1 folding table), 712; 784; 897, (xiii)-xvi pp. Plus atlas of 175 plates. This is the “Marine” section of Pancoucke’s massive 200-plus volume encyclopedia, which itself was an expanded version of Diderot’s 27 volume effort. It includes a plate volume of 175 engravings showing all phases of marine technology. The three text volumes are arranged alphabetically by topic, and discuss such things as shipbuilding, docks, waterfront fortifications, flags, sails, signaling methods, naval strategy, and anchor forging. These books were products of the Enlightenment - attempts to categorize and collect all knowledge. As such, Pancoucke’s Encyclopédie Méthodique is an up to date compendium of everything that was known about marine technology in 1780. It is of great historical value. This set is in brilliant condition, with pages crisp. clean and untrimmed, and engravings sharp and clean, with no foxing or offsetting. Bound in 19th century half calf over marbled boards. $3500

(Posted on Bookman’s Log, presented here by permission of the author.)