Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Adrian Harrington Rare Books

The Best Lack All Conviction. Part 1

By Bibliodeviant

(I’m not sure where this is going yet, but it’s going to be spread over the next week or so with me thinking aloud and trying not to be dull or obvious…fingers crossed for that happening)

We had a person the other day who just didn’t get it. Her daughter got it; she was giddy with Austen, besotted with Emily Bronte and oddly fascinated with Anthony Trollope, if she could have stayed all day quietly sitting in the corner, she would have. Her mother; not so much.

It was the money that baffled her I think, she couldn’t get why you’d want to own a hand coloured Culpeper first edition when you could own a coffee table version for a fraction of the price. I’m not saying she was mean, or greedy or ignorant or anything of the sort, absolutely not, we discussed various authors, literature, art; she was a voracious reader. I’m guessing that she could just not equate the objects I was showing her with any idea of “value”.

In a way this is an excellent attitude; cut through the pretentious art-speak from the ginger eejit with his unpleasantly long fingers and get down the actual facts … it’s a bit of old wood and dead goat and he wants two thousand quid for it. For some reason (and this is what I’m thinking about, not how people don’t understand me and I must run off and play some Smiths), people are happy, ecstatic even to buy a car, or a watch, or a vase or a pair of shoes for enough money to feed me for six months … but when they look at a book; they don’t see it. It doesn’t say “You want me. I’m your treasure.” It doesn’t make them not want to eat for six months so they can own it.

A sensible person, the kind of person that I am utterly not, would say that it takes all sorts; that if everyone was the same the world would be a tedious place. Then they would move on.

She left with her daughter, one of them clutching our latest catalogue as if it contained by proxy some of the value of the things it represented, the other amused and tolerant, a parent humouring a phase. This week it’s books, next week it’s a nose piercing. J.K. Rowling gives way to Veronica Roth.

Apart from feeling like I’d failed slightly, as if I’d somehow let down my vocation by not being able to represent it properly (a recurring theme), it occurred to me that my world is an arrogant one in many respects. Rare book people can often be like teenagers in love, they’ll burn the world down for the objects of their desire.

Which made me ask; why?

Why are we like this? More so in many ways than antique dealers, or sellers of fine art we represent the manic obsessive depths that antiquarianism can lead one to, bibliophiles carry with them the grubby hint of a passion turned to fetish; the object not the essence has become the focus of slightly unhealthy desire.

There’s another blog post waiting to be written about rare book-dealers in fiction. I’m willing to bet more of them will turn out to be the Devil in disguise than otherwise. We are seldom seen in a bright light: We dabble and delve and we know things we shouldn’t and Oh Dearly Beloved, there are always more things to unearth and to know. We are keepers of secrets, we speak our own language and we don’t share our business; it is hermeticism turned trade, grand alchemies gone to market.

But more than this.

You need to know some of the things that books are, before you can decide if they are what you care for, what you recognise as treasure.

Amongst other things they’re wood pulp and dead goat, this is true. It’s also true that I am made of hair and bone and little teeth (and bits of fibre and a myriad of unsightly secretions). I have it on good authority this is a somewhat simplified way of looking at me (although depressingly accurate), the same is true of using that as a definition of a book.

Their primary purpose, way back in the primordial mists of human thought, was as a method of recording, transmitting and sharing information. The information could (and was) be anything; how to build a barn, what plants could be eaten and which were poisonous, what Eumenus had said about Hector, which direction to sail in to find China.

Factual, fictional, religious, secular, practical or fanciful; the creation and proliferation of the book made it possible for all these concepts to be shared widely by something other than word of mouth for the first time in human history.

Starting with clay tablets, moving through papyrus scrolls, the bamboo butterfly books of the Tang Dynasty (I just really wanted to write that sentence), the codices of Mayan America (codex actually originally meant “block of wood”, the other two most familiar root terms “liber” and “biblos” actually refer to wood pulp or pith, so maybe that definition wasn’t too far off) and eventually through the ancient knowledge obsessed cultures of Greece and Rome, the tremendously ancient and erudite civilisations of what used to be Persia and is now a playground for arms dealers, down to the point at which the existence of my breed properly gained a foothold (in Europe anyway) during the medieval period.

As soon as we humans discovered we had something to say, and had formulated a symbolic way to say it (nearly all writing started off pictorially, as a little tiny drawing of a thing which represented another thing in the mind of the person who saw it) we couldn’t stop ourselves.

There is however far more to be said about books than that they are efficient receptacles of knowledge and information, second only to our own brains in terms of space, flexibility and breadth. They’re that too.

In our culture they serve more diverse purposes than can be described by someone with my glaring limitations (so naturally I’ll go ahead and give it a try).

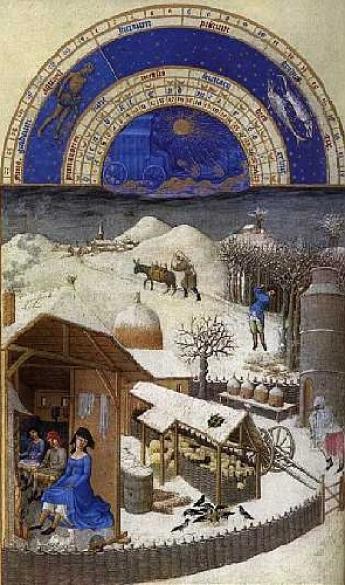

Medieval manuscripts depict gaunt scribes at work in their cramped monastic carrells, transcribing and rubricating the works of St. Augustine and Aristotle and writing tiny human editorial in the margins “Thank God it will be dark soon.”, “I am so cold and this man wrote so much.”

Their abbots, kings and princes however, are depicted seated next to shelves and cases of these books, intended to symbolise the wealth of wisdom they had at their fingertips, and also, not incidentally the actual wealth they possessed; a book that took a scriptorium of talented men weeks to transcribe and decorate was not going to be cheap, if you had twelve books you were not only a person of great learning, you were a person of substantial wealth. A significant donation or a commission might result in a member of the nobility being commemorated in illuminated form in a Book of Hours for example, giving us some of the only portraits from life we have of the luminaries of the time; converting a literal article of faith into an actual piece of documentary evidence.

But more than this.

Books then, were power given form. Knowledge had always been power, now that power was portable, tangible, it could be hidden away to be used when needed. Similarly the knowledge could now be stolen, smuggled, hidden, translated and transcribed. It needed to be jealously preserved, protected. In the same way previous men and women of power would be seen surrounded by weapons, armour, horses and hounds, the new breed of movers and shakers would add books to their potent displays of bling, books on an equal footing with weapons.

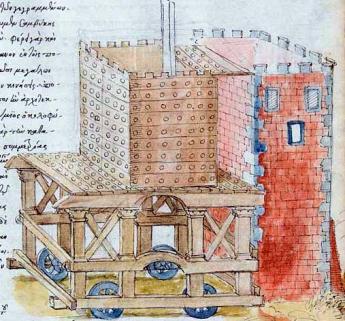

If you wished to destroy an enemy’s castle, then you could obtain (at great cost and/or difficulty) a copy of Renatus’s De Re Militari, the 5th century guide book to all forms of military tactics, logistics and leadership for example, the relative rarity of copies, translations and variations on a theme that must have been circulating would be impossible to guess at. The value of such a work to someone with the resources to use it would have been enormous.

The mysteries of explosives, the intricacies of building and operating siege machines, the methods of motivating men be they mercenary, conscript or volunteer, what the weather is like in the Alps in April, which rivers are in flood when and what happened when Flavius Aquila charged his cavalry uphill against a fixed defensive position. These things could all (quite suddenly) be found in books; the practical alternative to trying to keep knowledgeable, gifted men alive in times when, even without war and conflict, life expectancy was less than half what it is in the modern world.

Throw in some half decent maps, tidal charts, pilot’s rutters or periplus (if you’re feeling classical) and a few details about what makes the natives happy and you have the tools to conquer a world, or at least the portions of it that you know to exist.

Books also contain the motivational and aspirational means to drive you to look for parts of the world that you merely believe to exist; it was reading the travels of Marco Polo that inspired Columbus to go exploring, and look how that ended up.

This is before Johannes Gutenberg and his movable metal type gave rise to a form of mass book production. Imagine what happened after that momentous point in human history. As an event that’s right up there with the internet, with the original formulation of written language, that’s Episode IV important.

But more than this.

They can be seen as portable repositories of the secrets and tenets of a myriad of faiths and sciences. They are and ever have been best ally of the heretic and the revolutionary.

The right book could bring empires and churches to their knees, the writings of Galileo (1632; Dialogo Sopra i Due Massimi Sistemi del Mondo ) and Copernicus (1543; De revolutionibus orbium coelestium) carried the fight for enlightenment up to the gates of Heaven themselves and altered the shape of the known universe.

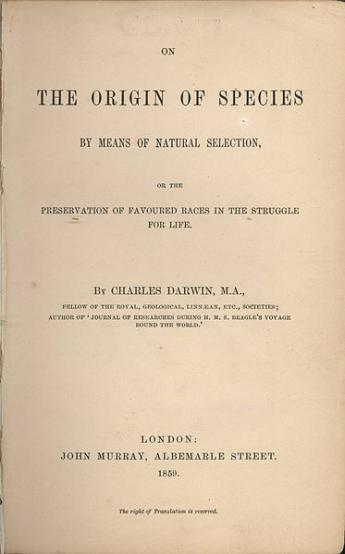

Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) permanently changed the expression on the twin faces of science and faith. One the one hand there’s no God because we don’t need one (not that Darwin personally thought so), on the other hand if there is one then he’s waaay more into detail and the long haul than we originally thought.

Fifty years before Origin the followers of Cuvier and Lamarck were arguing in Parisian cafes over the relative virtues of their opposing theories; Cuvier’s idea that catastrophes shaped the development of species, Lamarck’s that all diverse species evolved from simple organisms and were thus related. Their respective books (amongst an Alexandrian library of others) trickle down to Wallace and Darwin and their ilk, kick-starting their own studies and there you have it, Galapagos Finches and beetles and David Attenborough is on the gravy train for life.

All this was taking place against the backdrop of an immediately post Napoleonic France and an ascending British Empire (busy filling its own libraries and museums from the looted treasures that Paris was stuffed with; Napoleon, like most emperors, being apparently partly descended from a magpie) even though we’d already bid farewell to the Americas.

The reason that someone as ignorant as myself knows any of this … is because someone wrote it down.

Just think about it. Pretty much every fact, idea and concept recorded prior to 1877 (the invention of the phonograph, for the sake of facile argument, my favourite kind) has reached us through a book.

Since the beginning of recorded history, through clay tablets, scrolls and sheets of papyrus and parchment right the way up to the possibility of an alternate medium first reared its comparatively inefficient head…all down to books and the written word. Dreams, hopes, fears, prejudices, ignorance and wisdom all transmitted through the supremely democratic medium of books. It would probably be fair to say that books produced us, as much as the other way around.

So why don’t people see them as valuable?

to be continued…

(Posted on Bibliodeviancy - book lust unbound … Presented here by permission of the author.)