Stuart Kells

By Stuart Kells

Transcript of a talk given by Stuart Kells at a gathering of the Redmond Barry Society at Kay Craddock Antiquarian Bookseller in Collins Street, Melbourne

It is a pleasure to be talking to you this evening. When Dianne and Kay generously invited me to speak to the Society, many different topics came to mind. I will attempt to cover several of them: how I became a bibliophile; some highpoints of my bibliophilia, with a focus on two books of special importance to me, both of them published anonymously; how I came to write Rare; some points about Rare; and a few final remarks about the future of books. Covering all these topics in 25 minutes might be difficult. We will soon see whether I can fit all these clowns into one Volkswagen.

The answer to how I became a bibliophile is that I was always one. The first entry in my first diary is a tidy list of all the books I owned at the time. The bibliomania intensified in 1995 when Trinity College chapel had a book sale. I was first through the door and noticed immediately across the room a narrow leather spine with raised bands. In no time the book was in my hands and I was feeling the straight-grained morocco.

The book was published in 1814 and was called Pieces of Ancient Poetry from Unpublished Manuscripts and Scarce Books. The author was identified only as ‘N. Y.’ The colophon revealed that 99 copies had been printed, plus six special copies on blue paper. The copy in my hands was printed on blue paper, and was in great condition. The price was less than a coffee. The binding may have been made by Charles Lewis, a celebrated nineteenth-century binder who was criticised for dressing above his station, and wearing tassels on his boots. The author was John Fry. He was born in 1792, became a bookseller, and at the age of 18 edited a book of poetry. He later expressed his regret at what he called his premature appearance in print. Pieces of Ancient Poetry was released four years later, when Fry was 22. It contains poems by Donne as well as raunchy popular ballads, several of which were censored in the book. More than any other, this book set me on the road to full blown bibliomania.

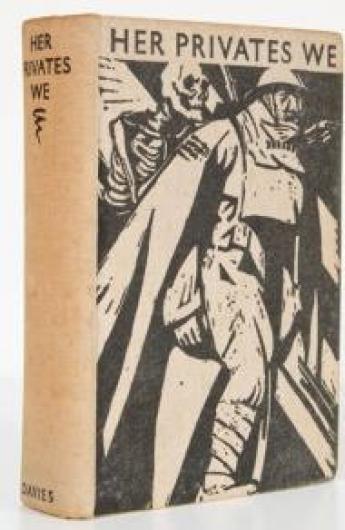

Another stage in my book development occurred in the late nineties when I joined Text Publishing as the editorial assistant. We decided to publish The Middle Parts of Fortune, a story of soldiers’ experiences on the Western Front. The book was out of print in Australia, and poorly known outside literary and academic circles. It was first published in 1929 by Peter Davies. Due to the raw dialogue, Davies feared the book would be censored. He created a Paris imprint, the Piazza Press, and issued a small number of copies. The following year he issued an expurgated edition under the title Her Privates We, with a striking cloth cover.

In both editions the author was identified only as Private 19022. In fact the author was Frederic Manning, an Australian who enlisted at the advanced age of 34 and saw action on the Somme. Manning was a fastidious writer. According to legend, Davies locked him away to force him to complete the book. When it appeared it was a great success, earning praise from Hemmingway and T. E. Lawrence.

In 2000 the book was out of copyright and we decided to issue the unexpurgated version, which had never been published in Australia. To prepare the typeset pages we used a new method of digitally scanning the text. Unfortunately, the software didn’t work, and the resulting digital version of the text was littered with errors. In tracking them down I got to know the book very well. A few years ago I was fortunate to find a copy of the original Piazza Press edition, and it is now a prized part of my collection.

Having learnt a bit about publishing at text, I started producing books on a small scale, specialising in books about books. Most recently I co-published Colin Franklin’s memoir, Obsessions and Confessions of a Book Life. In 2005 I published Kay’s memoir, ‘What’s in a Name’, which was I think based on a speech Kay delivered to the Australia Club. The memoir was brief but intriguing, and I could see that there was a larger story to be told about a successful Australian woman, and that it might be of wide interest.

I came to see Kay to ask if she would participate in the project. That first discussion had something of the marriage proposal about it. Kay was seated. I pulled up a stool and sat immediately in front of her, lowered my voice, looked into her eyes... And she said ‘I will’. Kay gave me access to the diaries she had kept since her teens, to her meticulous shop archive, and to her own memories. I’d like to give you three examples of primary material from Kay’s archive. The first is a poem by Les Craddock. It is simply written, but, for people who know about Les’s life, very moving.

Across the Sea

A little girl looked o’er the sea,

And asked ‘Why doesn’t father come home to me?’

A seagull flying in the sky

Said ‘Little girlie, please don’t cry;

I know your father’s coming soon,

He might be there by next new moon;

When all of this December’s passed

I think you’ll find him coming home at last.’

And when he comes you’ll all be gay—

Mum and Dad and Pat and Kay;

He’ll bring his clothes and home will stay;

And never, never go away.

The second piece of primary material is from Kay’s diary of her first trip to England. Kay was in her early twenties, and was staying at the Fielding Hotel.

Up early – packed - the man on the desk phoned and asked if I had got some accommodation - said not to mention it to anybody there & to go down & see him in 10 mins before he signed off. I thanked him & started to dress - was just finishing my dressing when there was a knock on the door - I fastened up the buttons on my dress, left hair curlers in & opened door - it was chap from desk who hurried in & closed door! - I felt a bit uncomfortable & he just stared at me - ‘Are you the young lady who wore the green frock last night?’ I said I was - he replied that he’d been so taken with my ‘looks’ that he wanted to help me! Said he knew a man who had apartments to rent & if I’d ring him (Mr Scampi) at 5.00 he’d give me the number - he said I looked completely different then from last night - & that make up made a great difference! ... he was a young chap, from Egypt, who was in England on a Teaching Scholarship - said he had night porter’s job to help him make money - didn’t have time to see many girls, but was very selective - and offered to devote what time he had off duty to me! I thanked him & murmured something non-committal - trust me to have such things happen!

The third piece of primary material is a letter from a Japanese oil man.

Thanks to Frank Clune and his Ned Kelly’s Last Stand, before coming to Australia, I was well armed with those phrases such as ‘as game as Ned Kelly’, ‘Ned Kelly was a gentleman’ or ‘Such is Life’ etc, etc. On the 23rd August, ’72, ten days after my arrival, there held the first Australian Antiquarian Booksellers’ Fair at Monash University. Though I hadn’t got even a slightest notion of local geography, when I saw advertisement on The Age, I decided at a glance that I should visit the fair by all means. The evening came and I duly went there by taxi all by myself scarcely knowing what was awaiting me on my way home. At the hall, I found your stand and bought a very good copy of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy ($15)...I spent considerably long time and when I came to myself, there scarcely remain other customers and I went out of the hall. It was moonless night and to my astonishment, it was pitch-dark outside and I can’t find my whereabout. Except black night, not a figure, street-light, vehicle was to be seen and I crawled my way nearly on all fours, with much difficulty, came to Wellington Road. I waited and waited nearly an hour on roadside, until as if by a miracle, a vacant taxi passed by and I was saved at last!

The same Japanese gentleman recalled another Melbourne bookseller thus: Quite jovial and talkative, during my three years stay in Melbourne, whenever I visited his shop, his eloquence rattled like a machine-gun and I was unable to look around bookshelves, reluctantly left the shop empty-handed. As a result, books coming from his shop are not so many.

To write Rare I took leave from my day job, and Kay gave me a desk at the rear of her shop. For me, a highlight of Rare is the story of the Hamilton collection. Alex Hamilton was a municipal rates collector in Ballarat. In a humble miner’s cottage he compiled a world-class collection of modern first editions. After a long negotiation Kay bought the books and they were delivered to her home in 147 tea chests. Her 87th catalogue featured 454 items of twentieth-century literature from the collection. There were five Samuel Becketts: Endgame; his ‘Three Novels’ Trilogy; Happy Days; How It Is; and a fine copy of the first English edition of Beckett’s novel Murphy in an equally fine dust wrapper.

To catalogue Murphy, Kay needed to set a price, but information about the market value was scarce. The book appeared only once in the available book auction guides, at a modest price. Using this as the basis for a considered guess, Kay priced the book at $95. The catalogue was despatched, but no Australian collector or bookseller ordered the book. When the catalogue reached a select list of booksellers in Britain and America, hell broke loose. The firm was besieged by orders from overseas dealers. Tom Goldwasser of San Francisco’s Serendipity Books was the lucky one who bought the Murphy: his relative proximity to Melbourne gave him a postal advantage over his rivals from Britain and from America’s east coast.

The Hamilton Murphy later sold for £3500. At the time of writing Rare, that particular copy was on offer for £62,500. I checked the internet earlier today and it appears the Hamilton Murphy has been reduced, to £50,000. Rare has been reasonably well received in the book fraternity and has introduced the antiquarian book world to a wide variety of other readers. The book demonstrates that people still value books as physical objects, and that the digital revolution has not entirely laid waste to traditional bookselling and publishing. I want to end with a few remarks on anxieties about the future of books.

Each book can be seen as an amalgam of five parts: one big idea, three crafts, and hard work. The big idea is the use of symbolic letterforms to link the inner lives of writer and reader. This idea worked because writers and readers made sympathetic and complementary investments in technique and imagination.

The three crafts are ink-craft, paper-craft and binding-craft. Ink reproduces the symbols; sheets of paper carry the ink; and leather, cloth, glue and cord bind the sheets together. All three crafts saw technical innovations over the past thousand years. Iron inks gave way to turpentines which in turn were replaced by synthetics. Wood pulp superseded rag paper and vellum. In bookbinding perhaps the biggest innovation was the paperback. The fifth element - the hard work of distribution - is how the book ultimately reaches the hands of the reader.

The printing revolution of the 1450s was primarily an innovation in ink-craft - a change in how ink was applied to the page - with secondary consequences for the other crafts and for distribution. The success of Gutenberg’s Bible lay in how beautifully it mimicked the manuscripts it replaced.

Seeing the book as a bundle of five parts helps clarify the digital book phenomenon, which is upending all three crafts simultaneously - no more ink, paper and glue - and is transforming the physics of distribution. The implications for printing, publishing and bookselling are massive, but the changes for writers and readers have so far been less profound.

Like Gutenberg, e-book manufacturers have strived to imitate prior technologies. Matt cream paper is simulated, and the sensation of turning a page is aped by animation.

The impacts of e-books on the crafts and distribution have led to much anxiety, but there has been less concern about the big idea. Yet that is where e-books could do most harm. When e-books mix text, hypertext, sound and video this is widely seen as an advantage of the technology. When Gandalf meets the Balrog the e-book page can dissolve to show Peter Jackson’s cinematic interpretation of the encounter. The scope for similar morphings of text and vision is infinite: Lyra consulting the alethiometer, Bond charming Octopussy, Holden catching in the rye.

An alternative interpretation, however, is that these morphings interfere in the private and magical communication between author and reader. There is a risk that plain text will lose out in the competition with more glamorous page fillers, and we will destroy the imaginative connection of writers and readers. In my view, therefore, we should be more anxious about the threats to the big idea at the heart of the book.

(Published in BOOKFARE, the newsletter of the Australian & New Zealand Association of Antiquarian Booksellers (ANZAAB), presented here by permission of ANZAAB and the author.)

Read more:

>>> Kay and Muriel Craddock - Rare. A Life Among Antiquarian Books. A new book by Stuart Kells