Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America

Prints as historical evidence: Lincolns deathbed

By Chris Lane

The assassination and death of Abraham Lincoln on April 14th and 15th, 1865 sent a shock throughout the nation, generating an intense desire by the American public to find out details about this tragedy. Printmakers, both for illustrated newspapers and for separately-issued prints, met this public interest with an outpouring of images. As there was no television nor internet at the time, and as there are few photographs of any of the events surrounding Lincoln’s death, these prints provided the public at that time with their only visual assess to the assassination and its aftermath. Similarly, today these prints provide us with some of our very few contemporary images of these events. As with all historic prints, the question must be raised as to how accurate these prints are, that is, how can we judge these prints as historic records of the events portrayed.

The two most popular subjects for contemporary prints were images of the assassination itself and of Lincoln’s deathbed. Today I’ll consider prints of the latter. After Booth shot Lincoln, he was carried to a first floor bedroom of a boardinghouse owned by William Petersen, which was located across the street from Ford’s Theater. There Lincoln lingered for many hours, dying early in the morning of the 15th. Throughout the night a regularly changing group of mourners paid their respects. The prints made of Lincoln's deathbed are supposed to show the scene shortly after he breathed his last.

A boarder in Petersen’s house took a photograph of the deathbed shortly after Lincoln’s body was removed. This shows a small room with four prints hanging on the wall, none of which are easily identifiable. Within three weeks, on May 6, 1865, Harper’s Weekly published a wood engraving of Lincoln’s deathbed. A comparison with the photograph seems to indicate that this image is fairly accurate. The room size, location of the door, wall paper and placement of the prints match the photograph. The Harper's image has more detail in some places, for instance showing more clearly the four prints on the wall. According to George Townsend’s account (from The Life, Crime, and Capture of John Wilkes Booth, 1865), the three large prints on the wall are John Frederick Herring’s ”The Village Blacksmith” (seen at the far left), Rosa Bonheur’s “Horse Fair” (seen over the head of the bed), and Herring’s “The Stable” or the “Barn Yard,” and one can actually recognize these images in the Harper's engraving.

According to Townsend's account, there were twenty-four people present at the time of Lincoln’s death. Given the size of the room (around 10 x 15 feet), this is probably an exaggerated total. The Harper’s engraving shows only twelve people, all of whom - except Surgeon-General Barnes - are listed by Townsend as being present. All the details of the Harper's print match up very well with what we know about the scene. No source is given for the image, but it seems reasonable that it was drawn - perhaps from memory - by an eye-witness or an artist who visited the room and talked to some who were there. Whatever the source, everything about this print indicates it is a close rendering of the actual scene.

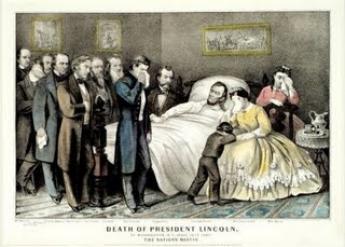

The same cannot be said about other images of the scene that were issued as separately-issued prints. The earliest to be published seems to be a Currier & Ives print, “Death of President Lincoln” (Conningham: 1500). This was copyrighted April 26, 1865, which means it was probably drawn about the same time as the Harper’s image. This print matches some of the details of the Harper’s print, but differs in a number of ways. The small size of the room is correct and the same number of mourners are included. The three larger prints on the wall are shown, with the “Horse Fair” even more recognizable, but the “Village Blacksmith” is shown reversed and the other Herring print is the wrong size and appears to be the wrong print. Robert Lincoln, some of the cabinet members, and General Halleck are all correctly shown as present, but Mary Todd Lincoln is also depicted as present, which is incorrect. Rev. Phineas D. Gurley, who was present, recorded that he broke the news of Lincoln's death to Mrs. Lincoln “in the parlor below.” Also, Tad Lincoln, shown crying in his mother’s lap, was never brought to Lincoln’s bedside.

As Harold Holzer has pointed out (Lincoln Seen & Heard, p. 63), Currier & Ives very shortly afterwards issued a variant issue of this print, also entitled “Death of President Lincoln” (Conningham: 1501). While the scenes are very close, it seems like the later print was from a new stone, for the frames of the prints on the walls are quite different. The main change, however, is the switching of two heads from those in their first print. The head of the gentleman sitting on the far side of the bed has been switched to someone else's. (In the second version of the print, this figure is identified as the Surgeon General; I do not know how this figure is labeled in the first version, nor why the face was changed - if anyone knows, please let me know!), and also the second man standing at the foot of the bed has been modified. In the first version, this was (accurately) General Halleck, but in the second version, Vice President Andrew Johnson appears in his stead. Johnson did visit Lincoln's deathbed, but only briefly, and he was not present when Lincoln died.

However, Johnson was then the new President and Currier & Ives likely felt that the print would be better received if he was shown as present.

Interestingly, Currier & Ives issued a third deathbed print, “Death Bed of the Martyr President, Abraham Lincoln” (Conningham: 1471). A number of changes have been made, most making the print less accurate. There are now 15 mourners in the room, and three figures - including Mary and Tad - are shown just outside the door. Johnson is depicted even more prominently here, standing by himself next to Lincoln’s head. Interestingly, the room has been reversed and the prints moved. Over the head of the bed is now a shelf upon which sits a clock showing the time of Lincoln’s death (7:30 am) and two prints are shown on the side wall. Herring’s “The Stable” is shown correctly, but now “The Horse Fair” is next to it, with no sign of the “Village Blacksmith.”

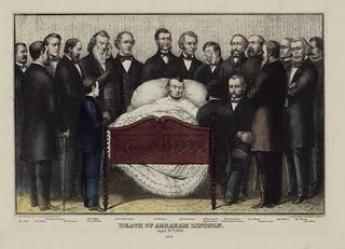

One of Currier & Ives chief competitors, as popular print publishers, was the Kellogg firm of Hartford. Like Currier & Ives, the Kelloggs issued a deathbed scene, “Death of Abraham Lincoln.” This is unlike any of the other prints of this scene, for the Lincoln is shown face-on from the end of the bed, with the eighteen mourners shown to either side. The wall paper looks accurate, and many of those who were actually present are included, but others who were not present, such as Tad Lincoln, are included and the layout of the room is incorrect.

Alexander Hay Ritchie was one of the leading American engravers of historical scenes; in 1865-66 had engraved a large print based on Francis B. Carpenter’s important painting of “The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet.” Perhaps the success of that print inspired Ritchie to paint an image of “The Death of President Lincoln,” which he then engraved and in 1868 published as a large print which he hoped would sell as well as the other had.

The image is interesting for its similarities and differences to previous prints. The room appears to be larger and the number of mourners has grown to twenty-six. However, Ritchie said he personally visited the room at Petersen’s and the wall paper, bed, rug and prints on the wall all seem pretty correct. Indeed, the three main prints on the wall all appear to be in their correct locations and they are quite clearly depicted in this engraving). Also shown is a fourth print, as had been described by Townsend. Though the number of mourners in Ritchie's image is probably exaggerated, Townsend did list just two less, so perhaps this print is not too far from historically accurate. Certainly the print was praised by a number of people who were at the death scene and no one at the time complained about its inaccuracy.

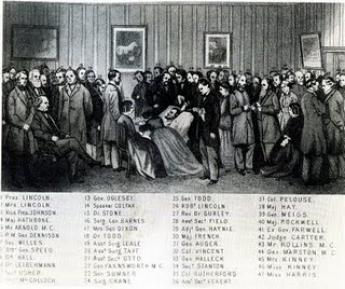

It is not clear how successful was Ritchie’s engraving, but this didn’t stop another artist of historical scenes, Alonzo Chappel, from trying his hand at producing an other large engraving of “The Last Day of Lincoln.” Chappel produced a large painting which showed the room, now grown substantially in size, filled with forty-seven mourners! Chappel did want his image to be accurate, so he based the portraits of all the mourners on photographs he convinced everyone to pose for. Though the painting was made with the intent of producing an engraving based on it, and though Chappel actually signed up many subscribers for the engraving - including Robert Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant - it seems that a print was never actually produced. There was, however, a key produced for the engraving which included a reduced version of the image and a listing of all the pictured mourners.

Though all the portraits in Chappel’s painting and intended print are based on life photographs, this is the most distorted image of Lincoln’s deathbed, for the room has grown far too big and there were never that many visitors in the room at one time. However, it is interesting to note that this image was praised particularly for its accuracy. For instance, the Washington Sunday Herald wrote of Chappel’s painting that “The greatness of the picture lies in its correct transcription of an actual scene and perfect portraiture of American men.”

I think that this indicates something about the way that such historical scenes were understood by viewers at the time, something which we need to keep in mind when we view these prints. Today, with photographs and video of almost any major event being readily available, we expect our images of these events to be accurate. Indeed we make special note when they are modified, for instance the famous photographs of Chairman Mao swimming when he was in fact too ill to do so.

In the 19th century and before, however, there were few photographs being made and so any images available to the pubic were based on drawings. The “news” prints issued in the illustrated newspapers were, to a great extent, intended to be accurate renderings of the events pictured, but I think that viewers at the time understood that separately issued engravings and lithographs were not to be taken as absolutely accurate portrayals of the events. These prints were understood to be as much symbolic or representational as “true to life.”

Separately issued historical prints were intended, certainly, to provide information about the events depicted, showing the basic situation and participants, but viewers expected the artists to take artistic license in putting together the scene. The printmakers understood that the public wanted the “whole picture,” not just a realistic “snap-shot” that a photograph might produce. For instance, in a battle scene, the intent was sometimes to show all the major events of the battle even when they never would have taken place within a single scene as the print might show. Similarly, with a view of a city, the artist would be expected to show all the major buildings and bridges, even if some could not in fact be viewed from the particular vantage point used for the drawing. Or, in the case of Lincoln’s deathbed, the public was probably more interested in seeing all the important figures who were on the scene at some point, rather than just the happenstance of who was in the room when Lincoln breathed his last. Print publishers often bent the literal truth in order to depict a more "complete" image and viewers at the time would have understood this.

Likewise, viewers also understood that the prints often had a symbolic role that was at least as important as the reportorial role. Prints of important events often were intended to convey a message, not simply to provide a “snap shot” of the event. For instance, no one thought that the cabinet all stood or sat in exactly the poses shown in Carpenter’s “The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet;” viewers realized the intent was to show the “essence” of the event, not the literal truth.

One print of Lincoln’s deathbed, that shows the symbolic intent very explicitly, is L.N. Rosenthal’s lithograph “The Last Moments of Abraham Lincoln,” where angels and George Washington look down on Lincoln from a bank of clouds hovering just over the bed. It is interesting that despite this print being the most blatantly symbol of the Lincoln deathbed scenes, it is also one of the most accurate. The room is about the right size (even accounting of the bank of clouds), there are only twelve mourners - all of who were probably there at Lincoln’s death -, the bed is the right kind, and you can even make out Herring’s “Village Blacksmith” on the wall.

Another clearly symbolic image, “Death Bed of Abraham Lincoln,” was published by John L. Magee. This was a mourning print for Lincoln, but also one that offered hope. Reverend Gurley is shown giving Lincoln last rites; this never happened, but it offered salvation not only for Lincoln but also for the nation. Also, the fictional hand-shake between Lincoln and Andrew Johnson gave blessing to the transfer of the Presidency and legitimacy for the new administration.

In future blogs I will examine further the issue of using antique prints as historic resources. The subject of this blog was inspired by the Smithsonian’s Online Conference Series session on “Lincoln’s Deathbed: Images of a Martyred President.” A recording of Pam Henson’s session on this topic is available on line at the Smithsonian’s web site.

The article was published by Chris Lane on antiqueprintsblog.blogspot.com and is presented here by permission of the author. Thank you very much.