Madame Guillotine

By Linda Hedrick

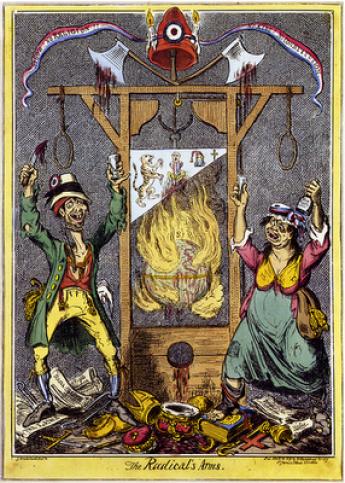

Before capital punishment was abolished in France in 1981, the guillotine was the sole method of execution. Made popular during the French Revolution, it was considered the "People's Avenger" by supporters, and the symbol of the "Reign of Terror" by opponents.

The breaking wheel, also known as the Catherine wheel or just "the wheel", was the preferred method of execution in the Middle Ages on into the 19th century. It was basically a huge wooden wagon wheel with lots of spokes. The condemned was tied to the wheel and beaten and the spaces between the spokes gave the club space to continue its arc. There were several adaptations of the wheel, but the one used in France involved tying the victim with limbs stretched over two wooden beams placed on a wheel which was slowly revolved. An iron bar or hammer was used to strike the limbs of the condemned in the spaces between the beams breaking the bones. This action was repeated several times for each limb, and dying could take hours, even days. If the situation merited "merciful" treatment, the executioner would commit "coups de grâce" (literally "blows of mercy") by fatally striking the chest and stomach areas. The luckiest of the French condemned would be granted a "retentum" or strangling after the second or third blow (or with extreme luck, before the wheel work began).

Another French word is associated with this form of capital punishment - "roué" - which means a "dissipated debaucheree". Its original meaning was "broken on the wheel" since this type of execution was reserved for atrocious crimes, while hanging was used for lesser crimes. Hence "roué" came to be construed as a man who was impious and callous, primarily thanks to Philip, Duke of Orléans, regent of France in the early 1700s, who used it to describe the bad male company he kept for amusement.

In 1789, Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposed a reformation of capital punishment in which he called for the same punishment for the same crime despite the status of the offender, that the family of the offender not be affected nor reproached on pain of judicial reprimand, that the offender's property would not be confiscated, and the body would be returned to the offender's family and no register of the manner of death be made. Most importantly, he called for decapitation to replace the wheel. The National Assembly looked for a new instrument of death, affirming the belief that capital punishment should be the ending of a life and not torture.

A committee was formed which included Dr. Guillotin and Dr. Antoine Louis. The committee was influenced by several instruments designed to decapitate, including the Scottish Maiden. The Maiden was built in Edinburgh. Once built it remained unused for so long it was dubbed the "Maiden". It was constructed in 1564 during the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots. This in turn was designed from the Halifax Gibbett, last used in 1650. The original stone platform was used as a base for a working replica erected in 1974 with a plaque listing the 52 people known to have been executed there.

Although the French device was named for Dr. Guillotin, he did not invent it. In fact he was against capital punishment, which is why he spoke out for ending the use of the wheel. Dr. Louis came up with the prototype design, which was build by Tobias Schmidt, a German engineer and Harpsichord maker. Schmidt is also credited with designing the triangular blade with a beveled edge instead of a crescent one. The first execution was done on April 25, 1792 for the highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier.

This was considered a more humane form of execution even for beheading. Prior to the device, beheading was done by a sword or axe, which usually required at least two strikes. This was also considered a blow for equality between the classes, as it was the only method of execution. Except for death sentences from military courts, which meant death by firing squads, this became the national execution type of France.

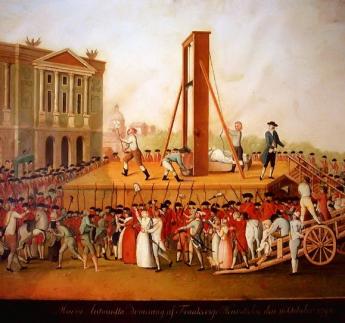

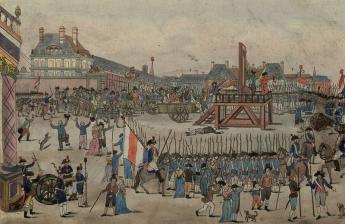

During the Reign of Terror, large-scale public executions were conducted, including King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, executed in 1793. Thousands were sentenced to the guillotine by the Revolutionary Tribunal, often on little or no grounds - mere suspicion of "crimes against liberty" was reason enough. Death estimates range from 16,000 to 40,000 during this time. The executions were popular entertainment and attracted huge numbers of spectators.

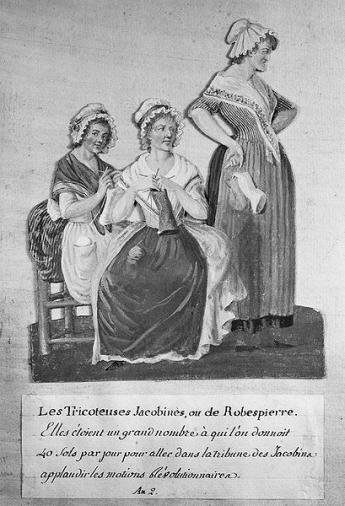

A group of female citizens, the tricoteuses ("knitters"), became regulars, functioning as macabre cheerleaders as they watched while knitting. The man most associated with the Terror was Maximilien Robespierre, and as the appetite for executions waned, he was arrested and executed in the manner of those he condemned - by Madame Guillotine.

The last public guillotining was of convicted multi-murderer Eugen Weidman. He was beheaded on June 17, 1939, but due to public behavior, the fact that it was secretly filmed, and the fact that the guillotine was incorrectly reconstructed, it was decided that future executions would be private. The very last victim of the guillotine was convicted murderer Hamida Djandoubi on September 10, 1977.

After all these deaths, France abolished the death penalty in 1981. Madame Guillotine had a healthy appetite but wiser heads eventually prevailed.

The article is published in Cerebral Boinkfest. It is presented her by permission of the author. The pictures show: The Radical’s Arms (1819), "The French Penalty" by Francisco de Goya (circa 1824), the execution of Marie Antoinette, by an unkown artist (circa 1793), "Les Tricoteuses" by Pierre-Étienne Lesueur (1793), the execution of Robespierre (1794).