Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco VII

By Umberto Pregliasco

Part 7

The love of learning, the sequestered nooks, and all the sweet serenity of books.

(Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

Catalogues in the Time of the Internet

Up to the Eighties, personal computers were not existing yet, and we could not even begin to think of scanners: the texts, typed on cards with bolds or italics highlighted with a red or blue pencil, were formed by the printer with the linotype; the illustrations used to be reproduced on zinc cliché applied on thick wooden blocks to be placed in the typographical shapes. In the past few yeas, computerized instruments have made everything easier, but the research for a greater and greater bibliographical attention and a more sophisticated graphic elegance, has paradoxically lengthened the time to complete a paper catalogue, destined to be consulted for years as a bibliographic source. While the descriptions reserved to a search engine are less charming and long lasting, because of the ephemeral characteristics of the internet. The same purchasing dynamics have changed: the bibliophiles of the past used to prefer saving on long distance calls and ordering from our catalogues, using the “low postage bookseller’s order form” or the already forgotten telex, and the telegraphic address “Preliber” is what we have decided to keep for our current web site.

Now we receive requests mainly via e-mail, with the right demand of pictures and more information. The internet revolution that we are living can only be compared to the invention of the printing press, that almost six centuries ago offered the world a democratization of culture that had been never seen before. The internet is radically modifying also book trading: the on-line offer for a very large number of antique or sold out titles has, undoubtedly, produced a greater transparency in comparison with the past: if through the different search engines we only locate one or two copies of a book, its rarity immediately becomes objective. But the opportunity of going through the pages of a nice paper catalogue is a feeling that cannot be compared to typing a title in a search engine: the dog ears that we make to remember an interesting item, underlining for a particular collation, represent a ritual that is really the characteristic of bibliophiles.

“When I read a book I seem to read it with my eyes only, but now and then I come across a passage, perhaps only a phrase, which has a meaning for me, and it becomes part of me.”

(W. Somerset Maugham)

If the web today allows us to find, at an unknown bookshop in another continent, a title that we had been after for a long time, consulting a catalogue still today allows us to come to know about books that we were not aware to desire and the existence of which was not even known to us.

By the way, some weeks ago I bumped into a brilliant Spanish web commercial that really amused me. It also rang a bell in my mind because was perfectly in line with my considerations about the differences that, luckily, still keeps the old fashioned printed friends competitive with the increasing new technologies. Here’s an abstract of that funny video.

“Introducing the new Bio-Optical Organized Knowledge device, trade named B.O.O.K. BOOK is a revolutionary breakthrough in technology; no wires, no electric circuits, no batteries, nothing to be connected or switched on. It’s so easy to use, even a child can operate it. Compact and portable, it can be used anywhere — even sitting in an armchair by the fire — yet it is powerful enough to hold as much information as a CD-ROM disc. Here’s how it works.

BOOK is constructed of sequentially numbered sheets of paper (recyclable), each capable of holding thousands of bits of information. The pages are locked together with a custom fit device called a binder which keeps the sheets in their correct sequence. Opaque Paper Technology (OPT) allows manufacturers to use both sides of the sheet, doubling the information density and cutting costs. Each sheet is scanned optically, registering information directly into your brain. A flick of the finger takes you to the next sheet. BOOK may be taken up at any time and used merely by opening it. BOOK never crashes or requires rebooting, though like other devices, it can become damaged if coffee or soda is spilled on it, and it becomes unusable if dropped too many times on a hard surface. The browse feature allows you to move instantly to any sheet and to move forward or backward as you wish. Many come with an index feature which pinpoints the exact location of selected information for instant retrieval. A Manually Accessed Retrieval Knickknack (MARK) allows users to open BOOK to the exact place they left off in a previous session - even if BOOK has been closed. BOOKmarks fit universal design standards; thus, a single BOOKmark can be used in BOOKs by various manufacturers. Conversely, numerous BOOKmarks can be used in a single BOOK if the user wants to store numerous views at once. The number is limited only by the number of pages in a BOOK. Users can also make personal notes next to and within BOOK text entries with optional programming tools such as Portable Erasable Nib Cryptic Intercommunication Language Styli (PENCILS).

BOOK is an environmental friendly product as it consists solely of 100% recyclable materials. Portable, durable, and affordable, BOOK is being hailed as a forerunner of a new wave of entertainment. BOOK’s appeal seems so certain that thousands of content creators have committed to the platform and investors are reportedly flocking to invest. In some areas, entire buildings are constructed to house BOOKs for public access.”

It was even more astonishing when I came to know that it wasn’t an original concept at all, but that the “Built-in Orderly Organized Knowledge” appeared for first time in a text by R.J. Heathorn, written in 1962.

A passage by Gustave Flaubert, taken from the work written during his adolescence Bibliomania, dwells upon the physical and psychological description of a bookseller named Jacques, ( James) the main character in his novel:

“He was thirty years old, but he looked old and worn out... he had a sinister and obscure look, his appearance was dull, sad and even a little insignificant. You would seldom see him on roads if not in those days where booksellers were holding auctions for rare books and first editions. Then he was no longer the same lazy and ridicule man, his eyes would be lively, he would run, walk, skip and he could hardly contain his happiness, [...] he would grasp his beloved book, he would protect it with his eyes, he would look at it, love it, just as a stingy person loves his treasure […]. This man had never spoken to anyone but the used book merchants and junk dealers; he was silent and dreamer, dull and sad, he only had one single idea, a single love, a single passion: books”.

An intervention made by Umberto kind of reconnects to the French writer’s text, it was for the occasion of a conference “the vertigo of the list” of his more famous Homonymous, Umberto Eco: “A catalogue is like an alibi to me, it makes separating from those books that I particularly love less painful, when I am forced to sell some so that I can buy some other ones. Having studied them and having published their description on one of my catalogues, allows that particular book, with that particular binding, with those notes of ownership, that water staining and those worms holes, to be still a little bit mine, anyhow, in spite of whom will own it in the future.”.

But, on the other hand, the hostility toward the world of Flaubert’s bookseller, does not really reflect what we believe to be a deep meaning of our job. The fame of an antiquarian bookseller is established by the publication of his own catalogues, in participating in public exhibitions, challenging himself and comparing himself with others, in informing all the scholars, and not only the buyer of that book, of his big and small findings. The book is by its own definition, a multiple, therefore the publication of a bibliographic information, a particular collation, an unpublished discovery, can and must be useful to be compared with other copies.

In the last century – then before the digital age – our antiquarian bookshops have been the crossroad of the Italian cultural history, a sort of Piazza Italiana, where, exchanging books and ideas, the people who “made Italy” such as Croce, Luigi and Giulio Einaudi, Gobetti, Pavese, Antonicelli, Primo Levi, Sciascia, Pontiggia, Calasso, Eco, met each other and formed their own taste and intellectual character.

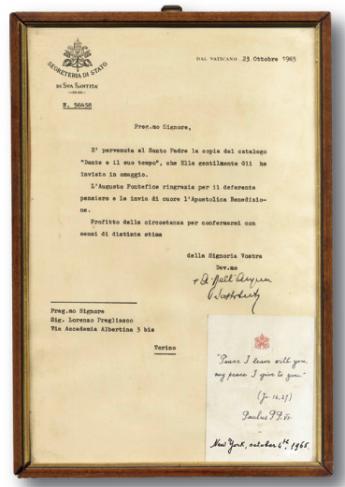

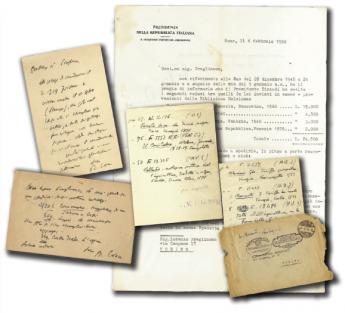

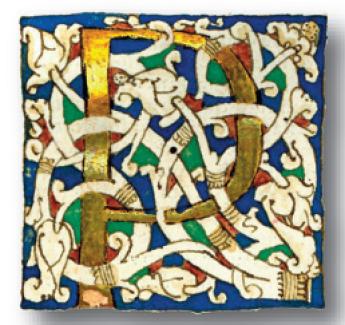

The history of the Libreria cannot exist without the people who have contributed to the century old success of the activity. In the picture taken at the beginning of the century, on the cover, we can see, near Lorenzo, his brothers, Secondo and Placido, and the precious errand boy Gepin. After moving into the current, more spacious area, Erinna, the wife of the founder, born amidst her publisher father’s art books, the Itala Ars publisher printed a very important work on the Piedmontese furniture. Erinna had an essential role during the thirty years that she dedicated with passion and competence to decorative and topographic engravings, on the first floor. And for a few years their daughter Giorgia took care of the market of autographs and historical documents, and then she followed her own way opening a manuscripts, affiches and posters shop. Arturo’s wife, Marisa, for a long time has been dealing with the accounting part of the business and as of today she does not give up the chance for a daily visit to hopelessly try to straighten up the ever present untidiness. For more than forty years Dario Barsalini has worked meticulously, and showing a great bibliographic expertise, in the preparation of very many catalogues, managing, in the beginning, to make ends meet between studying and working. The factotum Paolo Panero dealt in the sale of engravings and he carefully packed our precious books making sure that the clients would receive them intact. Since 1995, Elena, daughter of one of Arturo’s dear friends, Lorenzo Vanossi, journalist and bibliographer, works with enthusiasm and competence in indexing the books and in the management of the bookshop; in spite of the recent arrival of two twin boys, she still is an indispensable point of reference for Italian and foreign clients. Since 2004, after an internship for a specialization in History of Miniatures, Chiara Clemente has successfully become part of our staff, dealing with the accurate description of incunabula and manuscripts, a sector where she has also published a few essays. Furthermore, her inseparable retriever, Mia, has taken the place, on the soft carpet under the desk, that belonged to Artbook, the beloved dog that for a good sixteen years has accompanied Umberto to the bookshop, almost becoming able to collation the books...

Another Chiara has arrived in 2009 – just to make things a little more complicated as far as homonyms − and Francesco, Umberto’s eldest son. They are responsible for the on-line organization and publication of the books from the chaotic warehouse and of the website. Francesco also takes care of the graphic work and the catalogues complex layouts; while the younger son, Lorenzo, every once in a while deals with writing texts. This original historical excursus on our bookshop, but also on the book dealing world during the last century, has been possible also thanks to them. A fourth generation is being added, in the century old history of the Libreria Pregliasco: for sure this is our hidden dream come true. Living with books is the twofold meaning title that we have chosen for this anniversary catalogue, and we can clearly state that along with the rare books - and thanks to them –we really have been living for a century, and rather well. All those memories of the past, as well as the achievements of the present, lead our work with the same passion of our “founding father” – and grandfather, of course. “Amor Librorum Nos Unit” it is a motto we deeply believe in, which inspired us for 100 years. In this very spirit we want to share our anniversary, our joy and hopefully our books with you.

The final part of "Living With - And From - Books: A Century of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books of Literature, Fine Arts, Science and First Editions", published by Umberto Pregliasco on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco. The text is presented here by permission of the author.

>>> Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco

>>> Celebrating one hundred years of Libreria Pregliasco - watch the video on Vimeo