Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Oak Knoll Books

John Fuller and The Sycamore Press: A Bibliographic History

A New Publication of Oak Knoll Press

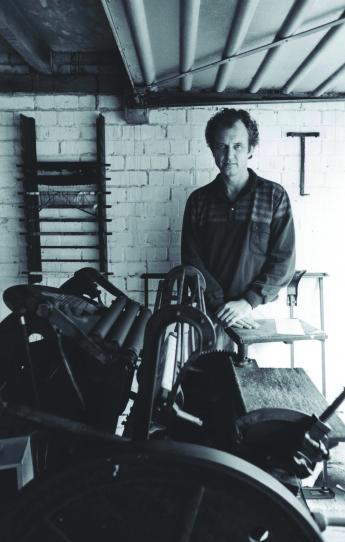

Set up in 1968, John Fuller's Sycamore Press published some of the most influential and critically acclaimed writers of the past half-century. Operating from a garage, the press published established authors like W. H. Auden, Philip Larkin and Peter Porter and young poets like James Fenton and Alan Hollinghurst. "John Fuller and The Sycamore Press", edited by Ryan Roberts, is more than a full descriptive bibliography. It includes personal reflections by Sycamore Press authors and an interview with John Fuller. Editor Ryan Roberts has met publisher John Fuller to find out more details of his press. As Ryan explains, meeting in Fuller’s home in Oxford, the conversation was casual, an enjoyable time to learn the facts of the press straight from the publisher himself.

An excerpt:

Roberts: So what determined, for the broadsheets, the number to be printed?

Fuller: I suppose we were influenced by the thought that with certain poets we could, in theory, sell a lot of copies. In other cases, I think we just went crazy when printing and there was more daylight than we thought and the paper was there and we just sort of went on for longer doing it. I think that was true of Bernard Bergonzi’s. We had printed a vast number. I seem to remember that it was purely accidental - just a sort of burst of energy. Because when you’re actually out there doing it - there’s the paper, it’s all inked up - you go on doing it as long as you can, until it gets dark. And you want to print them all in one day. So 200 copies is a fair number, but if it’s all going well you can get through many more. The thing goes ‘thwump, thwump, thwump’, and if you’re hand-feeding the paper in regularly and you don’t have to keep stopping for disasters you can get many more done. I think on certain days we found ourselves printing more than we really should have done. I think that’s the answer. It’s pretty arbitrary, actually. It’s to do with printing conditions and whether things have gone wrong or whether the daylight continued long enough for us to print. Not very serious reasons. How many did we do of Thom Gunn - 500? I must have thought, ‘This is Thom Gunn. I can surely sell 500.’

Roberts: And here we come to James Fenton’s Put Thou Thy Tears Into My Bottle.

Fuller: This is the one I misprinted the title. He didn’t seem to mind. I had some theological explanation for sticking with it, quite apart from the laziness in order to reprint the whole thing entirely, having done it. I think we could just draw a veil over that. No doubt if you don’t say anything about it being an error it will become a sort of postmodernist twist on the biblical text by James himself whenever somebody writes up his work. [Turns to Anthony Furnivall’s pamphlet] And then our attempt to print music. He was, I think, an organ scholar at Magdalen. I can’t remember exactly how I decided to print his song.

Roberts: So how did you go about setting the music for this?

Fuller: I used… you know that stuff, which in England is called Letraset, where you rub letters from a sheet? It’s got a slightly sticky back and when you rub it like a transfer the letter comes off. You can get ordinary fonts and you can get a sheet with musical symbols. I got staved paper, Letraset musical symbols, did a score and had a zinc-lined block made from it through a printer. I did the circular staves, by the way, with a pair of compasses. Quite tricky to do them neatly enough to reproduce, and then did the letters around. [Checks ledger book] There is an acute on Mallarmé, obviously, but I wouldn’t have been able to do that on my type. I certainly wouldn’t have done an accent on a little bit of type in the way that I described for the Larkin poem. Furnivall just set this Mallarmé poem, and I was rather intrigued by the challenge of publishing music. It just seemed an interesting technical challenge. And it was, really, because normally music is quite big - you prop it up on the piano and look at it from a distance. That was the largest size I could do getting those blocks into my forme, which is quite small. I seem to remember that the blocks filled out the entire forme.

Roberts: And then there are the Nemos … I’m considering separating them out from the rest of the bibliography, perhaps under a miscellaneous category.

Fuller: I think that in the sort of technical bibliographical sense it was just another of my activities that I brought under the umbrella of the press in order to help to market it. I think I thought I was simply going to account for it in the ledger as though I were publishing it, that I would include it for accounting purposes in case I was ever going to have to pay tax. In at least one instance, I ran out and photocopied some more. [Consults ledger] Yes, Truexpress — I must have taken my last copy along and had them do some sheets from it.

Roberts: So Standard Press would have done the original, but Truexpress would have handled the copies?

Fuller: Truexpress was just a little local print shop that would have given me something I could bind myself. I must have had a cover block made of the whole of the typographical cover of the Standard Press edition, just for convenience. And then I printed it on this yellow Glastonbury where I obviously had an awful lot of it as I’d used it often. So that was in 1973 that the press itself would have printed off the covers. I think Nemo’s presence in the ledger was just a sort of accounting thing. I sort of associated Nemo with the press, because I was doing the publicity postcards and it was something I was doing…"

"John Fuller and The Sycamore Press" is a book full of entertaining anecdotes about the hazards of small book publishing. It shows the powerful role John Fuller played in the lives of young poets lucky enough to be published by him, and it provides invaluable advice for small press printers.

"John Fuller and The Sycamore Press"

Edited by Ryan Roberts. New Castle, Delaware and Oxford: Oak Knoll Press and The Bodleian Library 2010. 160 pages. Hardcover, dust jacket. ISBN 9781584562818

>>> Oak Knoll Press

The excerpt was published in The Oak Knoll Biblio-Blog (January 20, 2011), and it is presented here by permission of Bob Fleck and Oak Knoll Press. Thank you very much.