How the trade in rare books has changed

By Lord Parmoor

Sometimes when an American millionaire or the Library of Congress spends a really large sum at Sotheby’s the public becomes aware of the export trade that is done in rare books. The issue of Boswell’s London Journal made people realise that the Boswell papers had gone to the United States, and it has become fairly widely known that Mr. W. S. Lewis, of Farmington, has collected the greater part of the papers and books of Horace Walpole. These are, however, only the highlights of the trade, the big deals but not the regular turnover.

Before the war London was the acknowledged centre of the international market in rare books. There were several reasons for this, the most important of which was that London booksellers were, in fact, the best in the world. They had, it is true, many advantages. Between the two wars many of the greatest collections in this country were dispersed, and this provided a continuous and rich supply. The London booksellers also had the benefit of a reputation won over a long period.

Quaritch was a great name in bookselling in 1900 as it is today. But there was more than this. The business of dealing in books is not compatible with quick profits on turnover. The most successful dealers are not those who buy books which they know they can sell straight away, but those who hold stocks.

The United States practice is otherwise. Most American booksellers act either as agents, buying to the needs of a few wealthy clients, or as opportunists buying to meet a temporarily fashionable demand. Any collector or librarian looking for a particular book is, even now, very much more likely to find it in the stock of a London bookseller than anywhere else. This willingness to hold large stocks for long periods goes with a permanent support of the market. A bookseller willing to keep a book on his shelves for five years will always be willing to buy.

He is thinking not in terms of the current price he can obtain for the book, but of its value in season and out of season. He is buying on his estimate of the book, not on his estimate of the collector’s immediate willingness to pay for it.

This trade used to be very diverse. One London bookseller could claim that in the pre-war years he had both bought and sold books in every country he could name on the map, even in Abyssinia he had bought a manuscript and sold a boo to Mr. Evelyn Waugh when he was a war correspondent in Addis Ababa. Much of this was the result of transactions in which books were bought in, say, Los Angeles and sold in Sydney, with London acting as the intermediary. Another consequence of the strength of the British market was that many foreign collections were sent to London for sale. This not only provided the auctioneer’s commission but gave opportunities to British booksellers both acting as agents and buying on their own account.

The trade is now much more restricted. Since the war there have been two obstacles to it. Exchange control has hindered, though not prohibited, the import of rare books, and export licensing has been used to stop the export of books and manuscripts considered to be of major national or historic interest. It is the currency regulations which are the most important. They have, for instance, prevented London auction rooms accepting some major collections from the United States because the proceeds of the sale could not be transferred into dollars.

At first sight this seems perfectly reasonable. It would be countenancing a luxury to allow scarce dollars to be spent on old books. But this is a short-sighted view. At the moment, as before the war, the book trade gives us a profit on balance. It does so because of the position London built up, and by liquidating stocks. But each year weakens our hold on the market, and stocks are running down.

It is a notorious complaint among booksellers that it is easy to sell good books, but very, very difficult to buy them.

Unless there is some arrangement by which our book trade is allowed to buy abroad as well as sell abroad, and the arrangement could, it is thought, be made to work, the market is likely to be lost. There are some objections. It is said that the trade is at best a small one. This is not possible to refute, for books are exported in many ways which do not appear in trade accounts.

A great number, of course, are taken out of the country in the baggage of visitors. It is also argued that one could never be sure that a books which was bought with dollars would be sold for dollars, but it is, of course, to the total proceeds of the trade that regard should be had. The point is that the book trade is an international one, with prices determined by international rather than national influences. Unless they can operate internationally the export traders cannot maintain their sales of rare books.

(The article appeared in the Financial Times of 8th November, 1952, and was reprinted in the ABA Newsletter No. 20)

More information

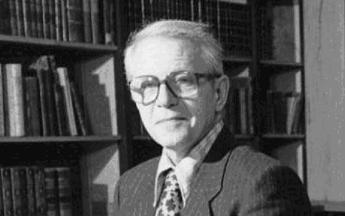

The 4th Lord Parmoor died in 2008, aged 79. Over a period of some 30 years he was the manager, the majority shareholder and finally the proprietor of Bernard Quaritch, the leading London firm of antiquarian booksellers.

>>> Read the obituary in The Telegraph

>>> The Worth of Rare Books. An interview with Arnoud Gerits>>> Do Rare Books Appreciate in Value? By Dan Gregory

>>> Some Thoughts on the Maturing of the Rare Book Market at the Start of the 21st Century. By Ken Lopez

>>> Rare Books as Investments. By Tom Congalton