Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Oak Knoll Books

Dreaming on the Edge - An Interview with Alastair Johnston

From the Oak Knoll Biblio Blog

Q: Why did you write this book?

A: The California Historical Society, where I used to be a volunteer, had a contest to find the best unpublished manuscript about some aspect of California history. I thought about it, and realized no one had ever written an overview of the book arts in the state, at least not since Louise Barr in 1930.

Q: How long did it take?

A: Three years. I wrote the first seven chapters in a rush to enter the CHS competition, but came in second. Not bad considering it was only a quarter of the book. But in addition to the three years of writing I had been thinking and even writing about this for a lot longer.

Q: What was your entry point?

A: Probably when I came to California in 1970 and found a poetry book by Jack Spicer, whom I had never heard of, that introduced me to the whole small press world.

Q: Did you continue in chronological order?

A: No, I conceived the chapters as stand-alone articles: the one about WET magazine started out as a book review on the booktryst blog, but then I kept rewriting and expanding it. I tried to make the tone light and journalistic and not academic. Once I had the framework I could see where I needed to go back and do more work. I also tried to limit it to one or two key books per artist to keep it focused and not go off into a whole history of each subject.

Q: I know you have already written quite a lot on this topic; what did you expand on and what new things did you bring to the book?

A: Over the years I have learned more and more about Auerhahn, White Rabbit, Zephyrus Image — small presses about whom I’ve have published bibliographies — also Semina magazine, Everson and Waldport, plus printers Graham Mackintosh and Dave Haselwood. Jack Stauffacher, who is now in his 90s, and the poets Philip Whalen and Joanne Kyger would relate to me personal stories or anecdotes which I stored away.

Q: What were your best discoveries?

A: Everyone has heard of Gelett Burgess and his Purple Cow. I went through his papers at The Bancroft Library and found not only letters and unpublished articles, but a prototype for an artist’s book called “How to Look Eleven Years Younger!” Someone should make a facsimile of it. Burgess wrote a great collaborative novel with his friend Will Irwin called The Picaroons. I was browsing the Will Irwin pictorial collection at Stanford and found a tintype photo of him identified as “Will Irwin and friend.” There are not many photos of Burgess as a young man, but there is a silhouette in the Lark and I found later photos and tweaked them in Photoshop to be the same size and orientation until I could make a certain identification. So that’s a remarkable find. At CHS I had a great time going through Haywood H. Hunt’s archives: there were so many wonderful photos of him, he must have been a real character. He is the one who had a secret bar in the back of his printshop.

Q: Were other discoveries as exciting?

A: I sent a draft manuscript to Victoria Dailey who writes very perceptively on the Southern California art scene and she told me about people I had overlooked — two in particular: Ida Meacham Strobridge and Merle Armitage. I had looked at Merle Armitage’s work but it has a New York imprint. It turns out he didn’t think that Los Angeles had enough credibility as a publishing center in the twenties so got a friend in New York to loan his imprint. There’s a story I retell of the printer of his monograph on Edward Weston setting fire to a forme to warm it up enough to take the ink properly. As Victoria Dailey herself wrote, “in an ironic twist three of the best artists in Southern California were not painters, but were Armitage, a book designer; Paul Landacre, a printmaker; and Edward Weston, a photographer.” So you have to alter your viewpoint. In fact you could also point to the presence of George Gershwin and film director Delmer Daves as key cultural figures in LA in the late 20s and early 30s. There was a lot of richness in art and architecture there in the 20s and 30s, particularly because of Hollywood and the arrival of German expatriates like Galka Scheyer, Thomas Mann, Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler.

Q: You are pretty tough on the Grabhorns and John Henry Nash.

A: I let their contemporaries explain the fundamental contradictions in their work. And I wanted to change the narrative which up to now has been about them as the exemplars of California presses. In the Nash-Grabhorn era it was still an elite world, financed by private patronage, but things changed in the forties with Bern Porter and in the fifties with Henry Evans, who are the true fathers of the small press movement. Then in the ’60s and ’70s we have the Women’s movement and even the NEA grants that funded small presses, as well as the obsolescence of letterpress as a commercial technology which led to artists adopting it.

Q: You tell some of these stories almost as if you were a fly on the wall, which is remarkable given the over a hundred-year span of the subject.

A: The oral histories of printers recorded by Ruth Teiser were inspiring to me, so it was important to get voices into the narrative. I met Saul Marks and Ward Ritchie, both of whom were born in 1905; I remember drinking with Lawton Kennedy (born 1901) in the 70s, but I don’t recall any of the things he told me about John Henry Nash and co. But I interviewed a printer named Thomas MacDonald (for the Book Club of California Quarterly) years ago and he had worked for Nash. In Santa Barbara I met a publisher named Wallace Hebbard, who had published a book called The Wild Gardens of Old California in 1927. His book includes six seed packets and, damn me, if I didn’t forget to mention it in the chapter on Brautigan’s Please Plant This Book, so obviously there will have to be a revised edition.

Q: Speaking of revisions what else did you omit?

A: I left out Gemini G.E.L. and Crown Point Press, since they are essentially fine art printmakers and not bookmakers. I did write something about Martín Ramírez, an accidental Californian, and one of my favorite artists, but couldn’t justify his inclusion. Obviously people will have their own perspective on what should or should not have been included. I tried to steer away from the pricy private press books that are so stultifying, not to mention hard to get to see. Many of the younger up-and-coming book artists will wonder why I forgot to mention them; mainly I did not want to just have lists, either of names or titles, but wanted to string together a narrative.

Q: Apart from courting controversy, did you encounter any problems in the production or compilation of your work?

A: Only in tracking down rights-holders for the images. The S. Clay Wilson chapter was a struggle. I wrote Ten Speed Press for permission to use an image and it turns out they were sold to Viking who are owned by Penguin. I got a letter from Penguin saying I would have to wait 6 weeks for a reply. After six weeks they asked again what it was I wanted to use (a small image in black and white); I explained the context and they sent me an invoice for $200 and I decided to forget it, and look further. I knew about Wilson’s edition of Grimm’s tales, which I had not examined and found there was a far more interesting story behind that, and wrote up Malcolm Whyte who is another neglected figure in the history books. So it worked out for the best, and Penguin, who didn’t even know they owned the rights to Ten Speed’s books, got nothing for their non-involvement.

Q: You found so many strange and wonderful books, do you own them all?

A: No, by no means. While I am not as compulsive as some of my friends, I do hoard old newspaper and magazine clippings, and turned up a Rolling Stone article on Ed Ruscha from 1971 that I had kept. But then when I volunteered at the CHS I discovered George Harding, the first librarian, had clipped every newspaper article he came across that mentioned someone in the graphic trades, even if it was just “So and So, printer, died at home in Eureka, May 1931.” It gave you a name and a date, and they were all filed in individual folders. I went through them all and put them in new acid-free folders. Despite the tedium, I found it occasionally inspiring and of course read every article in the process. One joy of volunteering is you don’t have to justify your time.

Q: One final comment to you as the designer: readers should be delighted by the many nice-sized images that make the book so appealing visually.

A: I wanted to see them well enough to read the small print — our eyes are not so good as we get older!

***

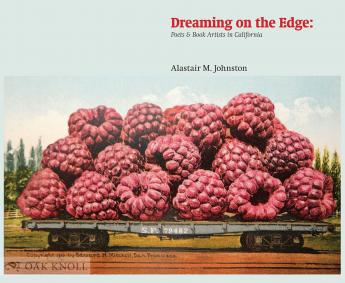

Alastair M. Johnston, Dreaming on the Edge: Poets and Book Artists in California.

New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2016. 232 pp. 10.5 x 8 inches. Cloth, dust jacket.

> Learn more

Posted on the Oak Knoll Biblio Blog, presented here by permission of Oak Knoll Press. Pictures: Oak Knoll Press.