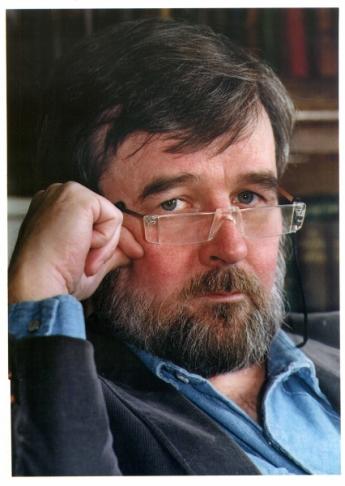

David Mason

By Barbara van Benthem

David Mason discovered his love of literature in a bathtub at age eleven, at fifteen he was expelled from school. For the next decade and a half, he worked odd jobs, bought books more often than food, and floated around Europe. He helped gild a volume in white morocco for Pope John XXIII. And then, at the age of 30, after returning home to Canada and apprenticing with Joseph Patrick Books, he found his calling. A few weeks ago Canadian author and rare book dealer David Mason published his memoirs The Pope’s Bookbinder. In his brilliant book he tells the most exciting stories of his legendary international career. An interview with David Mason about his career and the art of collecting.

First steps

I have been in the booktrade since 1967, when I began an apprenticeship with Joseph Patrick Books, then the best Canadiana specialist in Canada. I also issued catalogues in my own modern literature specialty which didn’t conflict with my boss’s.

At Joseph Patrick’s I met most of the important collectors of Canadiana in the country and, of course, all the major dealers. As everywhere, older dealers were kind and helpful but it was some years later before I realized that the collectors often taught me as much or more than the dealers did.

Bought, sold – missed

Probably the most important book I have handled was a presentation copy of the first edition of Darwin’s Origin of Species, which a man brought in off the street. That is not the most expensive book I’ve handled although it probably would be if I had it back in today’s market.

The art of collecting

All aspects of the trade, from scouting to collecting to navigating auctions, should help us understand history, art, or what we find valuable as a culture and why. But even more importantly the trade shows us the great things people achieve when they acquire books thoughtfully and with imagination. Here’s a story on the art of collecting that I think gets to the heart of the matter.

“The most complete modern philosophy collection anywhere in the world”

Collecting is an emotional process, a hobby which seems to so engage the collector and which provides so much pleasure and comfort that I believe monetary reward is of little interest. When collectors sell their collections or put their books up at auction I think the price realized is for the collector only a measure for himself - a tribute perhaps to his cleverness and passion - but not really a monetary concern. Some collectors plan to give their collections to institutions on their death - and some do it before. Some are of the school that believes that they should return their books to the open market to give later collectors a chance to own them. Mostly though, a man who has spent many years acquiring books and assembling a coherent collection by imposing his knowledge, experience and passion on a subject will be very proud, and rightfully so, of his accomplishment, and will want to have what in effect is his creation left intact both for future scholars and as a tribute to himself. For that is what a collection is. Whatever other value it might contain, a collection is a monument to the person who builds it.

We have a man in Toronto who obsessively collects all of modern philosophy (this would be from the early nineteenth century to today). This man previously formed the greatest collection of the work of Bertrand Russell in the world. A professor of philosophy, unmarried and therefore free of many constraints, he spent almost every summer scouting every bookshop in Britain and would return with three or four hundred additions to his Russell collection every year, in later years mostly magazine appearances, and often books where the index merely cited Russell, sometimes only once. Obviously he had the book-collecting disease badly and incurably by this time, the compulsion for completeness having become an obsession.

He once gave an address about collecting where he began by telling his audience that his collecting career had started when he collected the printed cards used to separate layers in the old style Shredded Wheat boxes. The roar of laughter which this elicited from the audience indicated that most of the rest of us had done the same thing as kids.

Anyway, this man, when he pretty much ran out of Russell to buy, focused his obsessional habit on the entire field of modern philosophy, and did so with the same intensity he had applied to Russell. Both his Russell collection and, later, his philosophy collection were gifted to the University of Toronto, and every five years or so two appraisers are called in to value the latest addition, which is so large it generally takes most of a week to appraise. This professor (his name is John Slater, as almost any dealer in the world will have guessed by now) usually drops by when we are about to start on the latest batch to point out things which might escape our notice. This is usually necessary because much of it is so obscure only another philosophy professor might know who some of these people are.

It was very common for John to show us a book, the author completely unknown to us, and inform us what a sleeper it was at £1 or £2 or whatever. This would no doubt be a very scarce book, but the real point is that no one else seeing that book would even know who the author was, nor care. So it was a sleeper only to the man who found it, as in this case.

One year John casually mentioned to me, “You know, Dave, my collection will now be the most complete modern philosophy collection anywhere in the world.”

“Well, John,” I replied, “I guess you mean the largest in private hands.”

“No, I mean anywhere in the world. I know that because I’ve checked my collection of American philosophy and it’s better than that of the British Library, and my holdings of English philosophy are better than what is in the Library of Congress.”

As I meditated on that later I realized that it indeed would be true. An important point. What that means is that one person, on his own, with imagination and passion, can supersede the resources of perhaps the two greatest public repositories in the English-speaking world. Think about that before you dismiss the private collector as a befuddled eccentric.

Behind the plastic curtain

Booksellers are often loners; bookish loners, with strong opinions and usually very independent characters, and as they get older, often very cranky ones.

There ís something about spending many years starving to death, offering the great works of civilization to people who don’t give a damn - while the friends one started out with become affluent or at the very least secure - to make a man take refuge in his own view of his social importance. There ís a great sense of freedom which comes with having nothing to lose, and when you mix that with having read thousands of books, by and about the innovators, rebels, and misfits of every sort and the geniuses who have left us so many stunning examples of creativity, moral courage, and obstinate defiance, it ís not surprising that the result will often be a cranky eccentric who doesn’t really care if you buy a book or not.

I was once in a bookstore in New York on the day before the New York fair, a shop which gradually filled up with visiting booksellers wanting to buy books. It was early morning, pouring rain outside, and the two elderly proprietors were viewing the hoard of hungry scouts with increasing suspicion and truculence.

One whole wall was covered with a clear plastic drape, protecting their latest catalogue - just being printed we were informed. The old men in charge didn’t like all this activity, we could tell: dealers greeting old friends loudly, water dripping from the new arrivals, the anticipation of great buys causing a lot of boisterous enthusiasm. We waited to see which of us would have the temerity to ask to explore the stock behind the plastic curtain. A friend of mine saw on the proprietor’s desk the very scarce and very desirable five-volume catalogue of the George Arents collection on Tobacco now in the New York Public Library.

“Is that for sale?” he courteously inquired of the old man who was eyeing him suspiciously.

“This is a bookstore isn’t it?” the crusty proprietor replied.

Even more politely my friend inquired, “May I ask how much it is?”

“It ís $450.00,” the proprietor barked, glaring at my friend.

“I’m a bookseller, you know,” my friend said gently, knowing the proprietors were aware that everyone in the store was a bookseller, but stating that just so there would be no doubt that he expected the customary trade discount.

“It’ll be 20%,” the man said, now noticeably angry.

“I’ll take it,” said my friend.

The owner softened a bit, but not much. A nice sale assured, my friend, feeling he had established his credentials as a serious man, notched things up.

“Could I take a look under the plastic, at the new catalogue?” he essayed tentatively.

“No,” said the old man bluntly. “And in fact we’re closing now - for lunch. You’ll all have to leave.” It was about 10 am.

And with that he threw us all out into the downpour, around fifteen dealers, hungry for books and with our bank accounts still full of money. Many potential sales lost, but they didn’t care. No noisy, snotty young punks were going to get away with such pushy tactics in their store. There was no way they were going to let us get away with giving them $20,000.00 or $30,000.00. My friend paid for the Arents (he sold it an hour later to another colleague for $750.00) and we slunk out. We all knew better than to protest at such arbitrary craziness; there was probably not a one of us who hadn’t done a similar thing for equally stupid reasons, defying normal economic sense, although certainly not with quite those financial consequences. We’ll sell the books to someone else sooner or later, they no doubt felt. We didn’t starve for fifty years to put up with those smart-alecky punks now that it no longer matters.

My supply of anecdotes concerning this sort of bookman is almost endless. If it is true that I, who have recounted stories of a seemingly endless supply of apparent imbeciles, am offering stories with the ostensible motive of amusing the reader, it should be understood that underlying our sly pointing-out of the eccentric foibles of so many bookmen is an enormous amount of true respect. So often, these apparent nuts, who might be incarcerated in mental institutions in a normal world, have a range and depth of knowledge in the areas that interest them which will astound anyone who tests that knowledge.

Markets

The rare book business has changed enormously. High rents in town centers have displaced the used and rare shops. Rare is in the country and at bookfairs, used is disappearing. This is the saddest and most depressing part of the current situation for me because used bookstores are the collector’s schools and they’re disappearing.

The internet is changing the entire world, just how and how much we don’t yet know. Again, time will tell but I think my generation will not see it.

Expectations

As always a dealer needs to learn his specialty; there will always be a place for the knowledgeable specialist and there will always be book collectors, so a dealer must learn his trade. And not expect to get rich.