Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Books Tell You Why, Inc.

Collecting - Ten Facts About Caldecott Winner, James Thurber

By Matt Reimann

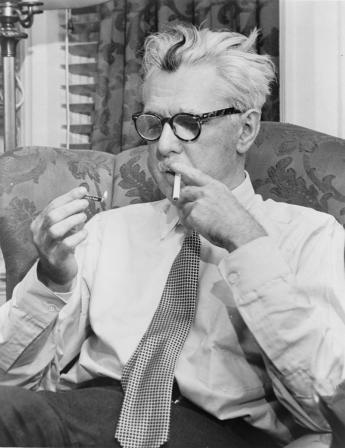

James Thurber was a short story writer, cartoonist, and humorist. Much of his work was published in The New Yorker, where he began working as an editor in 1927. His most famous short story is The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, recently adapted to film. Combining his talents for writing and illustration, Thurber had a successful career writing children's books, and won the Caldecott Medal for the book Many Moons. Below, read ten facts about Thurber's fascinating life and career.

1. As a child, Thurber's brother shot him in the eye with an arrow during a game of William Tell. James Thurber lost his left eye, and the incident left his vision permanently impaired.

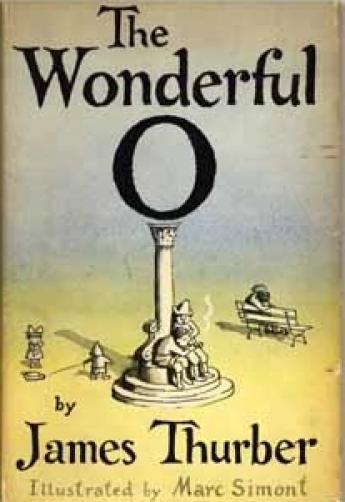

2. His poor eyesight proved a challenge for his writing and illustrations. As his sight deteriorated, Thurber took up the habit of drawing his New Yorker cartoons with a thick black crayon on white paper. By the 1950s, Thurber was legally blind. On his subsequent projects, he would enlist the help of other illustrators, as he did for his children's book, The Wonderful O.

3. He rewrote heavily, and depended on this editing to develop his work. Once, his wife remarked that a story in progress was "high school stuff." Thurber insisted that that would all change by the seventh draft. Thurber's editing habits were so rigorous that his story "The Train on Track Six," while only 20,000 words long, was cut from manuscripts totaling 240,000 words.

4. Thurber liked it brief. He said he never had the compulsion to write longer work. He admitted that the books he enjoyed most were short, like The Great Gatsby, The Turn of the Screw, and The Red Badge of Courage. He cited F. Scott Fitzgerald's preference for "taker-outers" over the sometimes tedious "putter-inners" of the literary world.

5. Thurber came in contact with the other side of the argument when he met Thomas Wolfe, whom Fitzgerald called a quintessential putter-inner. Lacking respect for Thurber's comparatively short New Yorker pieces, Wolfe refused to acknowledge the man as a writer at all.

6. Author E.B. White introduced Thurber to Harold Ross in 1926, founder and editor of the newly established New Yorker. He was soon hired to write stories and cartoons. Thurber would write a biography about Harold Ross, with whom he shared many memories throughout his career.

7. He had a photographic memory, and often found himself reminding friends of their own forgotten experiences. As a result, Thurber rarely took notes and kept a disciplined catalog of ideas in his head.

8. Thurber didn't often talk much about his work. For his interview for The Paris Review, it took some time for him to begin talking about craft, preferring instead to talk about the history of bloodhounds.

9. Thurber had a very easygoing philosophy about his cartoon work. In one cartoon, he had originally intended place a woman at the top of a staircase. However, he misjudged the perspective of the illustration, and the woman ended up on top of a bookcase instead. Whether the wife was alive or preserved via taxidermy is up to the reader's interpretation. Thurber himself had no idea if one was more true than the other.

10. His mother was a great inspiration to Thurber as a comedian. He remembered her as very funny. One running joke of hers was that she was usually kept in the attic because of her fondness for the mailman, a witticism she would share when company was over.

***

Posted on Books Tell You Why, presented here by permission of the author. Pictures: Books Tell You Why.