Tip

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions: Johann Froben and The Private Library

By L.D. Mitchell

He was the soul of honesty himself, and slow to think evil of others; so that he was often taken in. Of envy and jealousy he knew as little as the blind do of colour. He was swift to forgive and to forget even serious injuries ... He was enthusiastic for good learning, and felt his work to be his own reward. It was delightful to see him with the first pages of some new book in his hands, some author of whom he approved. His face was radiant with pleasure, and you might have supposed that he had already received a large return of profit. The excellence of his work would bear comparison with that of the best printers of Venice and Rome....

Erasmus, on the death of Johann Froben, 1527 (quoted in The Age of Erasmus by P. S. Allen, Clarendon Press, 1914)

Although his popularization of italic fonts and more portable texts gave rise to a famous epithetic comparison (the German Aldus), Johann Froben probably is better remembered today for his efforts to make texts as accurate and pleasing to the eye as possible, undertakings which brought him considerable contemporary fame, though not much money.

Born ca. 1460 in Hammelburg, Franconia (present-day Germany), Froben attended university in Basel. Early in his printing career he was an assistant in the Nuremberg workshop of famed printer Anton Koberger. Froben later moved back to Basel, where he became a corrector for (and later partner with, then owner of) the press of his friend Johann Amerbach.

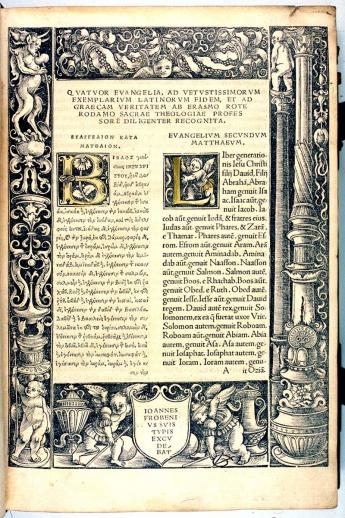

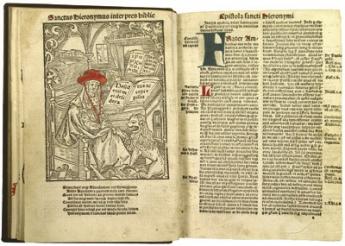

Froben's first publication, the so-called Poor Man's Bible of 1491, was the world's first pocket-sized Latin Bible . The second edition of this Bible, which Froben printed in 1495, became the world's first printed Latin Bible to include a woodcut illustration (by Albrecht Dürer).

It might plausibly be argued that Froben helped lay the groundwork for the various Reformation movements that convulsed 16th century Europe. These religious upheavals, which depended heavily on the wide distribution of religious texts and commentary in vernacular languages, can trace much of their driving force to innovations that Froben either introduced or improved upon.

Many of Froben's religious titles, for example, were (as noted above) printed in sizes that were far more portable (and thus more easily distributed, especially covertly) than the folios which traditionally had been printed for ecclesiastical use. Froben's Bibles were the first printed editions to include references to parallel passages throughout each volume. And Froben's 1516 printing of Erasmus' Greek New Testament Bible - which, with its parallel Greek and Latin texts, "focused attention on just how corrupt and inaccurate the Latin Vulgate had become" - served as the primary source-text for Martin Luther's enormously influential 1522 translation of the New Testament into vernacular German.

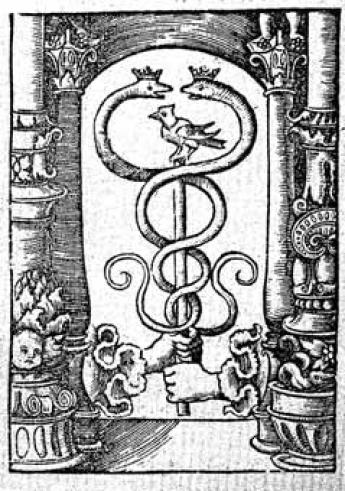

Froben's partnerships with other printers - e.g., Johann Petri (1496) and the aforementioned Amerbach (1500) - gave this distinguished printer access to an unusually large number of presses (for his time). And his long association with scholars like Erasmus and Beatus Rhenanus, and artists such as Dürer and Hans Holbein the Younger, insured both accurate texts and excellent illustrations. Little wonder that, by the second decade of the 16th century, Froben was widely celebrated as the most scholarly printer in all of northern Europe.

Of the 250+ titles known to have been published by Froben, perhaps the best-known and most revered today are those he published in concert with his client, collaborator and long-time friend, Desiderius Erasmus. Interestingly enough, Froben had first come to Erasmus' attention because Froben had pirated (in 1513) Aldus' 1508 printing of Erasmus' Adagiorum Chiliades. This was, however, no merepiracy, since Froben undertook several textual emendations, and praised Erasmus (on the title page) as "the ornament of Germany."

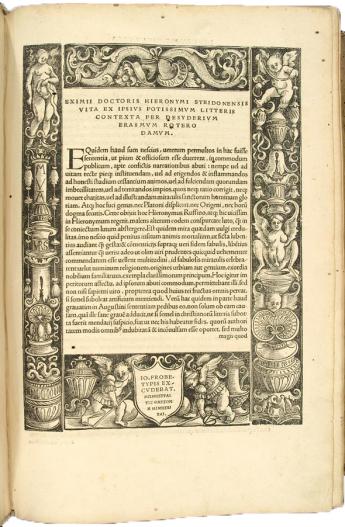

Perhaps this praise flattered Erasmus' intellect. As a book collector himself, though, it is more likely that Erasmus was drawn to the elegance and accuracy of Froben's printing, especially since Amerbach (whose presses Froben would shortly inherit) died before he could arrange to complete the printing of St. Jerome's Omnivm opervm, a publication that had been in preparation since 1507. Erasmus himself had invested much time and labor in trying to bring forth an accurate and scholarly edition of Jerome's complete works, and it was Froben and Erasmus together who finally bought this mutually compelling project to completion (in nine volumes) in 1516. (The copy below is held by the University of Rochester's Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation).After 1514, with very few exceptions, Froben and Erasmus were about as inseparable as any author and publisher have ever been. The distinguished humanist and the distinguished printer could not, it seems, heap enough accolades upon each other.

That said, Froben frustrates many modern book collectors.

We have yet to encounter a reliable, comprehensive, modern biography or bibliography of this extraordinary and influential printer. (Brandler's work “Joannes Frobenius: Eine Studie über den berühmten humanistischen Drucker des 16. Jahrhunderts“ is now a half-century behind us. Sebastiani's 2010 thesis “Il privilegio di pubblicare Erasmo : Johannes Froben (1460c.-1527), stampatore de Basilea“, which this author has not seen, might fit the bill if it could be expanded to encompass Froben's non-Erasmus publications as well).

Many of the most important articles about Froben require a reading knowledge of several European languages.

And Froben's own titles usually are beyond the reach of all but the few who have very deep pockets.

All this notwithstanding, the global economy is on life support, a situation which may yet benefit those book collectors who believe that fortune favors the patient....

This collecting tip was published in The Private Library. It is presented here by permission of the author.