Collecting - Famous Manuscripts and the History of Handwriting

By Matt Reimann

In the digital age, it is no secret that calligraphy is a dying art. Why work laboriously and imperfectly on something that takes days to cross the country, when the computer will set it in flawless text that can be transmitted instantly?

A careful look at the grand history of handwriting is not kind to the craft, either. Some historians consider Gutenberg’s press, the very device that liberated us from writing by hand, to be the single most important invention of the second millennium. Not only did it make books more accessible, it gave the works themselves unprecedented longevity. Think of all the masterpieces of antiquity (if you can bear) that were lost to rot and ruin because scribes could only produce a handful of them at a time. Aeschylus wrote some eighty plays, of which only seven survive. Shakespeare may have suffered a similar fate, as a writer who luckily had the printing press to immortalize his works - he leaves us with nearly nothing written by hand.

We can condemn handwriting for its inconveniences and inefficiencies. But that would mean ignoring the many hands that have worked and worked to provide us with our reading, our fulfillment, our culture. Below, we reflect on some of the most important manuscripts written by hand that we are lucky enough to have today.

The Book of Kells (c .800)

Because human history has in large part been preserved by the scribe, we include The Book of Kells as an exemplary piece of Western calligraphy, a culmination of a rich human tradition that has left lamentably little behind. The Book of Kells not only contains some of the finest handwriting known to Europe, for, as an artifact of bookmaking, as an illuminated manuscript, as a pure work of art, Kells has few equals.

Made around the year 800, The Book of Kells contains the Latin Gospels of the New Testament. Displayed in the library at Trinity College Dublin, it remains one of the few books in the world to attract vast swaths of tourists. The medieval writer Gerald of Wales reflected upon the book, “you might say that all this were the work of an angel, and not of a man.” And today, its visitors are allowed to be affected by much the same feeling.

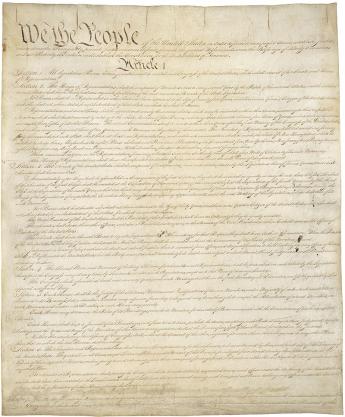

The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution (1776 and 1787)

The United States was built, and written, by hand. The Founding Fathers had an evident preference for writing their official documents. Jefferson, as the chief draftsman of the Declaration of Independence, worked through a series of drafts and consultations to compose the Colonies’ eloquent call to arms. Jefferson kept what is called the Rough Draft, a four page early version of the document, till his death. In 1947, the earliest known version of the document was found, called the Composition Draft. A third draft, known as the Fine Copy, is suspected to have been used for the July 4th, 1776 printing of the official Dunlap copies, but has not yet been found.

But nothing reveals the American love for the handwritten like the official draft of the US Constitution. Penned on four leaves of vellum parchment, a clerk named Jacob Shallus was paid $30 (around $800 today) to transcribe it. His hand dominates the document, although Alexander Hamilton’s handwriting can be found toward the end with the listing of the states.

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818)

In 1816, otherwise known as the Year Without a Summer, a group of talented writers were cooped up around Lake Geneva. John Polidori produced the modern vampire story, Byron composed his apocalyptic poem, “Darkness,” but most significant was Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, Frankenstein.

Lord Byron had posed a challenge for all of his guests to create a ghost story, which is apparently something the English are wont to do when it’s cold outside. The originalFrankenstein manuscript is held at the Bodleian Library at Oxford. What adds to the distinction of the papers is that there is not only one masterful hand at work in them. Two distinct handwritings can be found on its pages, one belonging to Mary, and the other to her husband, the poet Percy Shelley, who ultimately contributed some 5,000 words to the novel’s total 72,000. Through the manuscript of Frankenstein, we see the process of composition for all its collaborative richness - something we surely wouldn’t get had Mary enlisted her husband’s help via word processor or typewriter.

In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913)

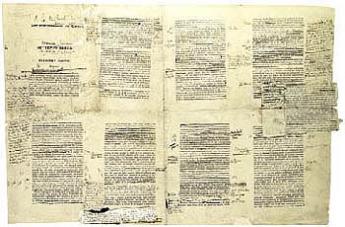

For any reader of Proust’s masterpiece, it is immediately clear just how dense the narration is. His descriptions are lengthy, his prose is jam-packed with commas and clauses. The longest sentence in his one and a quarter million word novel would stretch over four meters long, set in ten-point type.

For a gargantuan work, an equally massive manuscript was needed. Proust was always editing and revising, and part of what made his manuscript remarkable was the way in which he incorporated his additions and improvements. Being that rewriting entire pages would have been especially impractical, Proust frequently attached separate sheets of paper to his organizational draft, creating pages of manuscript that grew outward with more words - ever-expanding, like an ornate flower blossoming within a budding grove.

***

Posted on Books Tell You Why, presented here by permission of the author. Pictures: Books Tell You Why.