Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Ash Rare Books

Collecting Crime (Fiction) - A Very Shocking Shocker

By Laurence Worms

It was Simon Beattie who kindly put us in touch with a dealer on the continent who had this for sale. Not something he wanted, but thought we might. Quite what grounds he had for thinking this, I’m not at all sure – lurid, criminous, obscure author, published by a trio of even more obscure publishers, set in a vividly realised 1890s London, inscribed by the author, no copies on the internet – nothing at all there to appeal to me that I can see. As Simon himself likes to deal in ‘The Books You Never Knew You Wanted’ (see his delightful blog of that name: link in the Blogroll) – I suppose this by definition probably makes Death and the Woman one of those books you never knew you didn’t want – but then (to judge from recent sales) that’s probably becoming a fair summary of most of our stock.

Death and the Woman. A Dramatic Novel – by Arnold Golsworthy (1865-1939). Yes, it’s Golsworthy, not Galsworthy. Never heard of him, to be truthful, but a bit of delving soon came up with some answers. He was born on 25th September 1865 at 1 Foubert’s Place (just off London’s Regent Street – a cut-through to Carnaby Street) and baptised Arnold Holcombe Golsworthy at Whitefield´s Memorial Church on 22nd April 1866. He was the youngest of the half-dozen or so children of Thomas Golsworthy, a hosier (later a shirt-maker) originally from Holcombe in Devon, and his wife Elizabeth Storer Steel, herself a staymaker (and the daughter of another), who had married in 1854. A brief spell in Australia early in their marriage no doubt led to the naming of Elizabeth Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney Golsworthy.“In appearance Mr Golsworthy is a pleasant, gentle-faced man of moderate height and build. The eyes, brown and very humorous, are perhaps his most noticeable feature. For the rest he is three years on the right side of forty; married, very fond of Paris, and highly ‘accomplished’. He reads and writes in three languages, and has more than a bowing acquaintance with at least three others. Where books are concerned he is omnivorous, and the literature on his shelves runs with a pleasing width of range from Plutarch (his favourite author) and Herodotus, to the last French novel. When he is not working, he is out in the tennis court or the cricket field …”.

I’m perhaps a little sceptical about some of this – I can’t quite see the family finances running to what sounds like an expensive education, but certainly his ‘Jingle’ column had brought him a measure of contemporary fame and he comes across in the interview as droll and pleasantly self-deprecating.

He first came to notice with a well-received one-act play called My Friend Jarlet, co-written with one E. B. Norman, which was put on as part of the evening entertainment during Canterbury Cricket Week – a review in The Era (6th August 1887) calling it “a clever little play”. Further plays followed, co-written with Norman and also his Pick-Me-Up colleague, Henry Reichardt. By now describing himself as a professional shorthand writer and journalist, he married Jessie Ada Killick (1865-1949) – herself the daughter of a London hosier – in 1890. Their only child, a son, Ernest Edgar Golsworthy, was born in 1892.

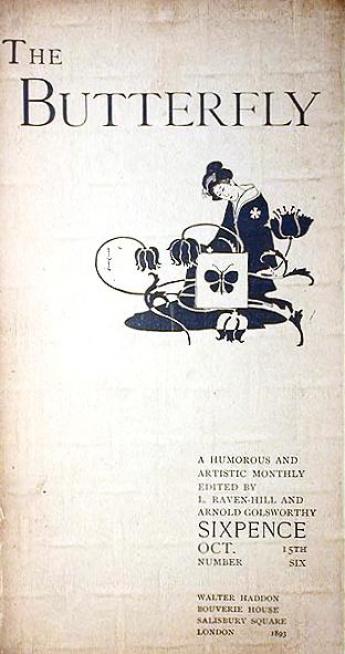

The following year Golsworthy departed in a new direction as the founder and co-editor of that delightful 1890s periodical The Butterfly – probably the one thing for which he is still sometimes still remembered. The Bristol Mercury caught the mood – this “dainty little magazine is very different from its contemporaries, and, turning over its luxurious pages, it is not difficult to understand why its success should have been so decided from the start. It is doubtful whether pen and ink art was ever seen to such advantage as in these pages of superbly reproduced drawings by leading artists.

Mr Maurice Greiffenhagen … supplies the frontispiece of the present number in the shape of a fanciful study of a mermaid sinking languidly through the waves which is as delightful as anything of its kind could well be … published at the low price of 6d, the new magazine is a marvel of cheapness”. Evidently too cheap – it only lasted ten numbers before folding (although it was briefly revived in 1899-1900 by Leonard Raven-Hill and Grant Richards).

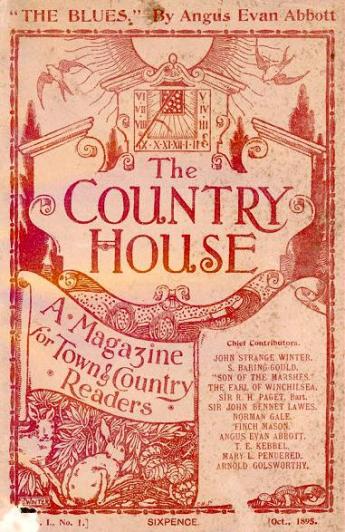

Proceedings for bankruptcy were commenced against Golsworthy, then living at 2 Solent Road, West Hampstead, in January 1894. Although the receiving order was rescinded a few months later, he seems from that point on to have looked for more viable commercial outlets for his talents. He stepped up his writing of short stories and amusing essays for magazines likeBlack and White, The Country House and The Idler and also commenced on a series of sensational novels, of which Death and the Woman was the first.

There is something puzzling about its original publication in 1895: no copy of that edition appears to be known, it is not represented in any major library worldwide, the reference books are completely silent and – both before and after publication – the 1898 edition pictured here was very specifically referred to as a new book. Were it not for a barbed review in the Glasgow Herald of 24th October 1895, I doubt we should know of the existence of an 1895 edition at all. “Thoroughly horrible”, the Herald found it, and worse still, “there is no mystery”: to add injury to insult the brief and dismissive review also gives away the ending. I have half an idea that the book may simply have been rapidly withdrawn and then rewritten to some extent before being announced as a new book a couple of years later.

The critics were kinder this time round, although still found the book disturbing. “Mr. Golsworthy knows how to cater for those who would sup their fill of horrors and purchasers of this gruesome narrative will not complain … the reader, like the spectator at a melodrama, is admitted to the secrets which perplex the actors. This adds to the interest rather than otherwise, and often lifts the book on to a higher level; but, at best, it is a very shocking shocker …” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 25th May 1898).

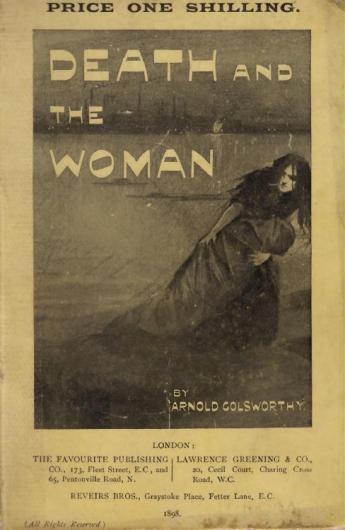

It is in truth a very odd book. A psychological thriller we would call it now and that it genuinely is. The action opens in the Blue Anchor, a little-favoured dockside pub in the East End, and alternates between there and more fashionable parts of London. The dialogue is good – as far as once can judge the authentic sound of late Victorian London – the writing a little melodramatic but entirely professional, but the plot, well, far-fetched doesn’t really quite cover it. All the interest is in the two principal characters – a strange and haunted private detective and master of disguise, and the raven-haired Ella Osborne, tall, graceful, “more than ordinarily beautiful” – half innocent, half calculating, half guilty, rescued from a circus in youth, half demure, half wild-child – she’s somehow innocently disposing of a body in the front cover picture. Nothing quite like her in the whole of Victorian fiction and worth a read on her account alone.

Although not made explicit in the book itself, the striking cover picture is actually by the great Sydney Herbert Syme (1865-1941) – or Sidney Herbert Sime in the spelling he later preferred: he was born on 15th November 1865 for all those of you who have been looking for this (or feel inclined to correct Wikipedia or the ODNB). Well known of course for his peerless illustrations for William Hope Hodgson, Arthur Machen, and above all Lord Dunsany.

Golsworthy followed up with Hands in the Darkness(1899) – a tale of buried treasure and murder at Hampstead, replete with secret subterranean passage, a cataleptic Frenchman, etc. A Cry in the Night (also 1899) was well reviewed as “a good example of the old ‘shilling shocker’ expanded to the size of an ordinary novel. We begin with the customary murder, for which, on this occasion, there at first seems even less motive than usual; then we have the false clues and the amateur detective; and at last the discovery of the criminal in an unexpected personage … superior to many of its class” (Yorkshire Post, 11th July 1900); “Told easily and without any tiresome digression … Altogether a capital tale” (Western Times, 23rd January 1900); “The writing is exceptionally good for this class of literature” (Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 14th January 1900).

Although translations of these sensational novels continued to have some success abroad, Golsworthy’s star was perhaps by now in decline. A humorous book,The New Master (1901) was apparently received with a “chorus of approval”, and he was listed as a playwright in Who’s Who in the World (1910-1911), but A Little World (1913) – a microcosm of the world found in a single suburban London street – was published under an ‘Arnold Holcombe’ pseudonym. He was still working as a drama critic for The Bystander in 1917 and writing for the Sunday Pictorial the following year, but beyond the publication of The Fanatic : A Drama in Verse (1925) he is little heard of thereafter. He died at his home at The Nook, Langley Lane, Ifield, Sussex, on 29th March 1939, leaving a modest estate to his widow, Jessie.

***

Posted on The Bookhunter on Safari, presented here by permission of the author. Pictures: The Bookhunter on Safari.