Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Ten Pound Island Book Company

Cataloguing Rare Books Sh*t Explosion

By Greg Gibson

Still too gimpy to drive across the state, so I was skipping the Albany Book Fair that weekend. But Dan Gaeta, who was doing the show, called to tell me about an interesting item he’d found. It’s nice to have friends! (Dan operates John Bale Book Co., a café and book shop in Waterbury, CT. Talk about a simple but effective website, check out John Bale Books). Anyway, since I’ve been home all week, grumpily compiling my next catalog, and since I don’t have a book fair to report on, I thought I’d talk a little about my catalogs.

Back in the 1980s when computers were new and fun, I stumbled across a Macintosh database program called Filemaker, and realized I could use it to organize my business. I studied the manual for weeks and somehow managed to cobble together a system that kept track of, and linked, customers, books, and invoices. Filemaker turned out to be a good choice. It is a powerful and versatile program, and is the core of several popular software products for the used book trade. My custom program is clunky by comparison, but it suits me fine. I only write a few hundred invoices every year. For a while, after I switched over to PCs, I kept upgrading the Filemaker software. But I stopped buying the new iterations when I realized they were WAY more powerful than my little mouse-on-a-treadmill operation required.

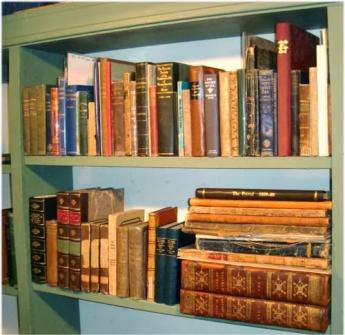

So, first I buy the book – I’ve talked plenty about that – then I collate it, also recording purchase price, date, and source. Then I research it, using Google, of course, but also my lovely reference library, of which I am only slightly less proud and fond than I am of my children.

Then I put the book on the shelf until it is surrounded by enough other books to make a catalog.

I like to keep my catalogs short because I believe my customers have limited time and attention for whatever I have to say to them. Fifty to seventy-five items are plenty. Also, I can issue short catalogs more frequently, smoothing troublesome cash flow bumps.

Then I begin entering each book into my “Books” database. This is where the bibliographic information and sales pitch for each title reside; also the description of physical condition of this particular copy.

As the years roll on, my “Books” file has become a labor saving device. At the moment I have 36.907 records in that file. Even discounting the many duplicate entries, the chances grow slimmer each year that I’ll find a book that is NOT listed in my database. Thus, most of the work of cataloging a book is done for me already. All I have to do is find the record that matches my title, update the condition description of the new copy, and maybe edit the sales pitch, and the book is cataloged.

Then I alphabetize and add numbers – automated functions – then I export the cataloged books to a Microsoft Word file and proofread it in that format, making simultaneous corrections in my “Books” file. Then I paste the corrected Word file into my page layout program (I use something called “Art Explosion Publisher Pro.” When things go bad I refer to it as “Sh*t Explosion”).

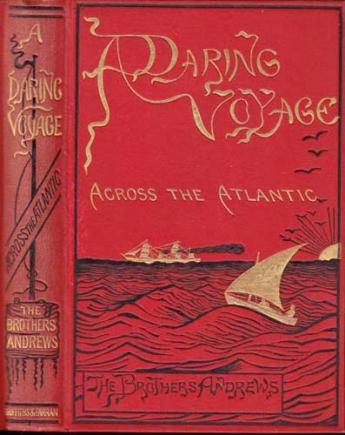

Then I take pictures or scans of the cataloged books. These are crude, quick snaps, taken with my little pocket camera, or with books sprawled upon the scanner bed.

Then I open them in Photoshop and size them, and adjust color and contrast. Photoshop is an amazing application. It does thousands of things – of which I know how to do exactly three – size images, and adjust their color and contrast.

The images I work with are the sort of images Dan Gregory, guru of book photography, scorns. But they seem to work for my customers. They convey a basic sense of the condition of the binding or the contents of each book.

Then I drop the images into the page layout program (this is where the sh*t explosion often occurs).

Then I make a PDF of the finished product and send it off to my printer. For more complicated layouts, I get my photographer son to do the job, and he sends the PDF off to the printer. I used to use a local print shop, but that got too expensive. So I switched to The Covington Group out in Kansas City. They turn the job over in a week or ten days, for about 2/3 the price my local guy was charging.

Then I make an html file of the catalog from my corrected “Books” file and get my son or long time helper Amanda to put the html file on my website and add the image of each book. Maybe they’ll put it on the website in PDF form as well, to give the customer an option for how they want to read the catalog.

Then I mail my hardcopy catalogs, priority mail, to my “premium” customers (It’s not hard to become a “premium” customer. All you have to do is buy something from me). Then, after two days – the average length of time it takes priority mail to land anywhere in the US – I send out an e-blast telling all my customers that a new catalog has been posted on my website.

The process has evolved over a period of twenty-five years or so. The “database file” for Maritime List #1 was a box of index cards. It was printed by me on a used AB Dick mimeo machine – talk about a sh*t explosion! Still, Maritime List 219 has a lot in common with Maritime List #1. Both are cheap, efficient, relatively low tech, easy for an old fool to make, and easy for a customer to read.

There’s only one problem that I can foresee. Some day I’m going to need a new computer. When that day comes, my Filemaker Pro 4.0 program, circa 1997, will probably be useless, unsupported by whatever advanced brain drives my new computer. Ditto my Art Explosion application, my old scanner and software, as well as my Adobe Photoshop 2.0.

Then I’ll be able to write a blog about learning how to do everything all over again at the age of 70.

(Printed on Bookman’s Log, presented here by permission of the author.)