Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Ten Pound Island Book Company

Can Your Kindle Do This?

By Greg Gibson

John Ledyard is a strange and fascinating American original. In 1772 he attended Eleazer Wheelock’s Indian School, which would later become Dartmouth College. Unhappy there, he went off with the Indians. When spring rolled around he built himself an Indian-style dugout canoe, threw a bearskin around his shoulders, and sailed down the Connecticut River to his people in Hartford. Several adventures later he accompanied Captain Cook on this third voyage and was present when Cook was killed in the Sandwich Islands.

It was during his tour with Cook that Ledyard, in a moment of deep and visionary insight, grasped both the unity of the American continent and the concept of trading northwest American furs for Chinese export goods. He became obsessed with the idea and spent the rest of his life trying to convince someone to invest in his scheme. He charmed the likes of Robert Morris, John Paul Jones, General Lafayette, Thomas Jefferson and Joseph Banks, but never found the backer he needed.

Frustrated, he set off walking across Russia and Siberia, bound the long way for the Arctic Sea, the northwest coast and a hike across the American continent. (Ledyard was Jefferson’s inspiration for the Lewis & Clark expedition.) He almost made it through Siberia, but Catherine the Great, perhaps protective of the Russian fur trade, had him hauled back and kicked out of Russia. He returned to London and agreed to explore the source of the Nile for Joseph Banks. But he got sick in Cairo, overdosed on purgative, ruptured a blood vessel, and died there, aged thirty-five.

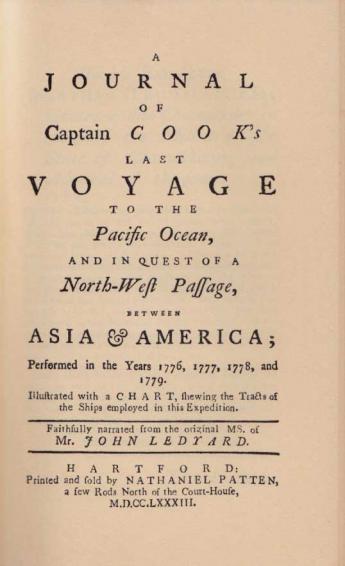

His body was never recovered, and his legend as “The American Traveler” probably would have dwindled and vanished - except for one thing. When he got back from his travels with Cook he wrote a book about his adventures, A Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean… Hartford. 1783.

It was the first American travel book. Before its release, Ledyard persuaded the Connecticut legislature to pass a law allowing him exclusive rights to its publication. This was the first copyright law passed in America.

For these reasons alone the book is historically significant. But it is also important as a controversial “alternative” report on Cook’s death, and as a publicity piece for, and prelude to, the American China trade. Despite its crudely set type and rudimentary route map, it radiates charisma. It is scarce in any state, but the very few copies published with the map are truly rare. Ledyard’s Journal has enormous cultural importance.

One day in 1994 I got a call from a gentleman in Los Angeles who wanted to sell his library. I’d only sold him a few books and had no idea of the stature of the collection he’d assembled. I asked him what he had and he named a few classics – Hakluyt, Cook, Vancouver, and books of that ilk. Very impressive! He also mentioned that he had a copy of Ledyard’s Journal. I asked him if it had the map. He said it did. I told him I’d be there in two days.

I was able to purchase that library, and I managed to sell the Ledyard for what I considered an excellent price. (I’d gladly pay twice that to have it back today.) Then I spent the better part of twenty years trying to figure out how write a book about this remarkable character and his oddly compelling life – which ended smack in its middle. Then, just this past summer, I realized how I’d do it.

To prepare for my proposed book I’ve been reading about Ledyard and his life. Somewhere in the course of my studies I learned that Laurence Sterne had been one of Ledyard’s favorite authors. So, when I tired of reading histories and biographies, I went to my shelves in search of Tristram Shandy. I first read Sterne’s book when I was in college and, like John Ledyard (this is probably the only thing I have in common with him) I fell in love with it.

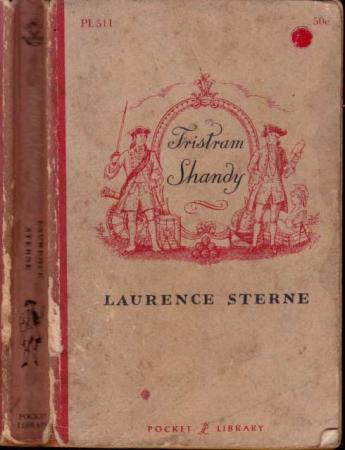

There on a dusty top shelf sat my copy, unopened in decades. It was a tanned and beat-up paperback, printed on cheap stock and set in minuscule type, inscribed in blue ink and dated by its owner, nineteen-year-old Gregory Gibson.

To my considerable surprise, that book turned out to be the key to a time machine. It only took a few lines for Sterne’s quirky voice to come back to me, transporting me to the May days of 1964 when I’d first read him, first held that book, squinted at that type, turned those flimsy pages. The soft air of the campus in springtime came back to me, and the voices of friends, and the faces of girls, and the love affairs, silly adventures, and precious relationships - all the excitement and confusion of those late-teenaged years filled me in a giddy rush, triggered as much by the sight and feel of that tired old paperback as by Sterne’s dotty, brilliant prose.

Thus the force of the book as physical object. Ledyard’s Journal, with the map, got me on a plane to LA and convinced me to put my house in hock one more time. And Tristram Shandy, inscribed by Gibson in 1964 made me nineteen again, for a few moments at least.

Two examples of the power of this obsolete analog information delivery system, whose attributes the Kindle and its descendants will never replace.

(Posted on Bookman’s Log, presented here by permission of the author.)