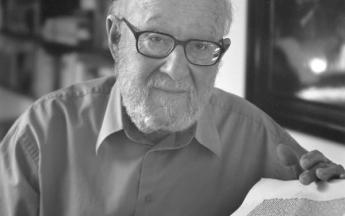

Bernard Rosenthal

By Ian Jackson, Berkeley

Bernard Rosenthal died in Oakland after a week’s illness on January 14th, 2017, at the age of 96. He was a Bavarian Tuscan who carried his spiritual home with him and found in California a snug harbor. His Florentine mother compensated for the German birth of her children by addressing them always in Italian. It was the language Rosenthal reverted to on his deathbed. Like his grandfather Jacques, the great Munich antiquarian bookseller, he wore his Jewishness lightly, although it was the key factor that brought him to Berkeley in 1939. It was here that he shed the H in Bernhard and soon became “Barney,” the nickname by which he was ever after universally known.

Barney was born in Munich on May 5th, 1920 to Erwin Rosenthal (1889-1981) and Margherita Olschki (1892-1979), daughter of the leading Italian antiquarian of his day, Leo S. Olschki (1861-1940). The Rosenthals were a legendary family of booksellers. Barney’s grandfather Jacques (1854-1937) and great-uncle Ludwig (1840-1928) were the leading German dealers of their day. His father traded as L’Art Ancien in Zürich, specializing in illustrated incunabula and Old Master prints. All three sons also dealt in books: Albi (1914-2004), the world’s preeminent dealer in antiquarian music books and manuscripts for over 50 years, Felix (1917-2009), who managed L’Art Ancien in Erwin’s old age, and Barney.

It is just possible to be born a Rosenthal and not become a bookseller — Barney’s nephew Jim, the British sportscaster, is a celebrated example of the contrarian spirit. But the escape hatch is difficult to find. Fortunately the Rosenthal family had an exit strategy from Hitler in 1933 (via Italy) and then from Mussolini in 1938. Barney’s route was via Paris and then New York. Barely a month after arrival, he moved on to Berkeley — an Italian friend of his had “made it sound as though there was no other university anywhere.” Warned by his father that all the good books were gone, he majored in chemistry and considered becoming a farmer. But the lure of the book-trade was too strong. Barney studied paleography in Zürich while apprenticed to his father, returning to America to catalogue for Parke-Bernet.

He ventured out on his own in 1953, trading from an office in New York City, specializing in early printed books and text manuscripts, and benefitting from the European connections of the family. Albi consigned medieval manuscripts, Rosenthal cousins in Holland (heirs of Ludwig) supplied bibliographical works, while Erwin sent over not only books but one of his employees, Ruth Schwab. Barney married her in 1969 and they transferred the business to San Francisco the next year, with a shop on Post Street. Over the years, in a leisurely series of contractions, Barney returned to Berkeley and reduced his scale of operations. His final office had been designed to hold a psychiatrist’s couch, but was perfectly proportioned for an elderly bookseller with a tiny stock.

It was only a year or two ago that he actually “retired.” When Barney first broached the subject in his early 70s, Albi told him “Nonsense, Barney! You’re far too old to retire!” His last two moves were made possible only by the sale of his large reference library, which tended to be at least ten times as extensive as his stock. Barney would often say that the book business existed to support the library. He attributed his fit and agile old age not just to a lifelong love of hiking in the mountains but to the strategic positioning of his office furniture, which obliged him to cross the room hundreds of times a day to consult his reference books. The Oxford Latin Dictionary, in constant use, was kept far from his desk, on a free-standing lectern — Barney was a great believer in upright learning.

A small stock, in turn, allowed him time for patient examination and interesting discoveries in almost every old book he touched. His masterpiece in this vein was to have been his Catalogue 34 of books, chiefly before 1600, with marginal notes by contemporary readers. He had been setting them aside for years. Yale, however, bought the books before publication, and published the catalogue as The Rosenthal Collection of Printed Books with Manuscript Annotations (1997). A small income, in turn, dictated that he would attract little commercial envy from his colleagues. Barney dealt in medieval text manuscripts, with few if any pretty pictures, leaving the glitz of illumination to others.

Not all of Barney’s publications were commercial. Three delightful if slender volumes mingle the personal with the historical: Cartel, Clan or Dynasty? The Olschkis and the Rosenthals (1977), The Gentle Invasion: Continental Emigré Booksellers of the Thirties and Forties and their Impact on the Antiquarian Booktrade in the United States (1987), and his own Autobiography and Autobibliography (2010).

Barney had a sunny temperament, on principle, and a smile for all that radiated an understated sense of joie de vivre. He realized that he was fortunate to have been born a Rosenthal. He also had a rare genius for friendship, with humans as well as cats. It was a reticent and elusive friendship perhaps, with behavioral elements of the gypsy and the will o’ the wisp, for he could seduce by keeping his distance. Barney was a master of what the Italians call cordialità protettiva — protective cordiality. His method of not suffering fools gladly was to avoid their company.

Though his charm was indefinable, and perhaps ever-changing, his fellow booksellers were drawn to it like moths to a flame. He was accessible to all, Hail Fellow Well Met around the world. How could one be intimidated by a man, so obviously learned, who seasoned his conversation with émigré and army slang from the 1940s — with such words as “creep” or “goofy”? As one of the last polyglots in the American book trade, he might raise an eyebrow at a solecism in your French or Latin or at some character flaw in a colleague, but he would then shrug his shoulders, and say, “Well, after all, at least we have books in common.” No bookseller more perfectly embodied the spirit of the motto Amor librorum nos unit — A love of books unites us.

Bene Vale.

Bernard is survived by his wife Ruth, son David and granddaughter Oriane.

This obituary by Ian Jackson was also published in the San Francisco Chronicle on 23 Jan, 2017.

Ian Jackson, Berkeley

ianjacksonbooks.com

To read a wonderful article by John Windle about the ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Booksellers) bookseller Barney Rosenthal, which was first published in ABAA Newsletter in Spring 2010, please click here:

Bernard M. Rosenthal Turns 90 - A Life for Rare Books and Manuscripts