Tip Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc.

Why Are Some Dustjackets Clipped but Not Price-Clipped?

By Dan Gregory

While browsing through Ralph Sipper‘s booth at this past weekend’s Los Angeles Antiquarian Book Fair, I came upon an interesting copy of book that at first seemed a little out of place at the fair: John Sanford’s Every Island Fled Away. It’s a 1964 novel that, these days, is typically a $30 – $40 book in collectible condition, and not that much more when signed or inscribed. Usually the booths at the three fairs sponsored by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America (there’s also a New York show in April and a Boston show in November) are full of the best antiquarian books for sale in the country and the world (read highest quality, and consequently highest priced). Dealers usually trot out their top material, and Ralph’s booth was full of many stunning copies of notable literary first editions. Some of them, like his beautiful copy of William Faulkner’s first novel, Soldiers’ Pay, are genuinely rare in such condition. By comparison, the John Sanford book seemed to be a grade schooler lost at the senior prom.

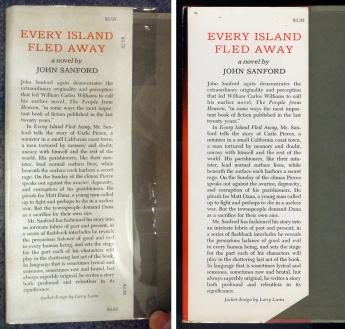

But as soon as I took the book off the shelf and had a look at it, I began to see why Ralph may have brought it. This copy, fine in fine dustwrapper, came from the author’s library and was inscribed by him to one of his publishers. But beyond that, this copy had four different prices on the front flap (clockwise from the top they were $3.95, $3.75, $4.50, and $4.95). By printing four prices in such a manner, the publisher, W.W. Norton, could leave the decision of the final retail price until later in the publication process. After the books were printed, and just before the printed jackets were to be folded onto the bound books, two or three cuts to a stack of printed jacket sheets could quickly eliminate the unused prices. It also allowed the publisher, if he were so inclined, to market the book at different retail values in different areas. And finally, it might have allowed the publisher to retail the book in Canada while compensating for exchange rates between the Canadian and American dollars. Given the inscription, and the uncut state of the jacket, it is reasonable to assume this was a pre-publication copy that was never offered for sale in bookstores in 1964, when the book was new.

I’ve seen uncut examples of four-priced flaps before, usually on books published by Macmillan – most notably on a very nice first edition of James Michener’s Tales of the South Pacific that we had many years ago. But uncut jackets such as this are uncommon and I didn’t think we had a photograph of an example in our archive (of course, we have a couple hundred thousand rare book photos in our archive, so it’s a little hard to tell). Joachim Koch of Books Tell You Why was a few booths down from Ralph Sipper at the fair, and kindly took this photo for me using his smartphone.

When I returned to the office I found that we also had a copy of the first edition, clipped along the bottom of the front flap, but not price-clipped and with a printed price of $3.95 at the top of the front flap. I assume all trade copies of the first edition (that is, copies sold in new bookstores in 1964) are clipped this way. And if you look for it, every once in a while you will find other books which similarly have multiple prices arranged so that they can be easily clipped away. Booksellers sometimes use the term “machine clipped” to indicate cuts on the jacket corners that were done mechanically to a stack of jackets during publication, rather than when an individual owner of the book clips the price away with scissors (either to give it as a gift or to resell it at a higher price).

So if you come upon a book whose jacket is clipped but not price-clipped, now you know at least one reason this may be the case.

John Sanford, by the way, is a rather interesting literary figure – he was a novelist and screenwriter who began publishing in the 1930s. Some consider him one of the best “neglected” American novelists. Called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, he and his wife, the screenwriter Marguerite Roberts, refused to name names and their professional output trickled to a stop for many years. Eventually their careers bounced back (among her many screen credits, Marguerite wrote the screenplay for the John Wayne version ofTrue Grit). Late in life Sanford seemed to make up for lost time – approximately half of his two dozen books were written and published after he turned 80, and reportedly he was writing right up to his death in 2003 at age 98.

Posted in the Between the Covers Blog, presented here by permission of the author.