Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Oak Knoll Books

Online Bookselling before the Internet

By Ed Johnson

In the fall of 1986, Karen Preslock, a librarian at the Smithsonian Institute, called me with an idea for a new business that would help book dealers, collectors, and researchers find and acquire books. At the time I was working in the Smithsonian rare book library, but prior to that, I had been a rare book dealer, which is why Karen approached me. She had thought of this idea through her many frustrating experiences trying to obtain out-of-print books for her researchers. She had tried using AB Bookman - a weekly book trade publication - but with no luck. And looking through the book catalogues of all the individual sellers was too time-consuming.

She asked if I thought book dealers would be willing to put their inventories into a searchable computer database. At that time the public was just starting to buy computers and the Internet did not really exist as it does currently - there were only companies like Prodigy and Compuserve who provided limited networked services like news and weather. I thought there was a real need for such a database in the book industry.

Over the next several months, Karen and I spent our lunch hours in the Smithsonian cafeteria thrashing out a business plan. In the end we decided to create a database to which book dealers would add their inventories and libraries would add lists of the books they needed - the computer would then match them. We concluded that we needed $ 50,000 to start the business.

In the spring of 1987, I left the Smithsonian in order to concentrate on raising money for the business. This fundraising ended up taking almost two years. During this time we brought Clark Easter onboard because his business background would make our company more appealing to potential investors. The business plan was revised many times and in the end our start-up costs grew to $750,000 - fortunately, that was still small change to a venture capitalist.

After attending a number of venture capital conferences and meeting with several potential investors, we finally chose Faxon, a company that supplied journals to libraries, to finance us. We thought Faxon seemed like a great match given their connections to libraries all around the world. In 1989, we signed a deal with Faxon which gave them 80% ownership of the company and split the remainder between Karen, Clark, and myself - and thus Abacis was born.

Abacis started with five or six employees, which quickly grew to more than ten, six of whom were devoted to library and dealer sales. I worked in dealer sales and within six months I got over 200 dealers to sign up. However, many dealers said they would never get a computer or that they were happy with AB Bookman. Many told us that our idea would never work.

Selling to libraries also ended up being more difficult than we had expected. Faxon was only a small help in convincing libraries to sign up, in part because their salespeople did not understand our aims. Therefore, we had to hire additional people to concentrate on sales to libraries. Over time we began receiving requests from the general public for access to the database; therein we saw an untapped market we could approach.

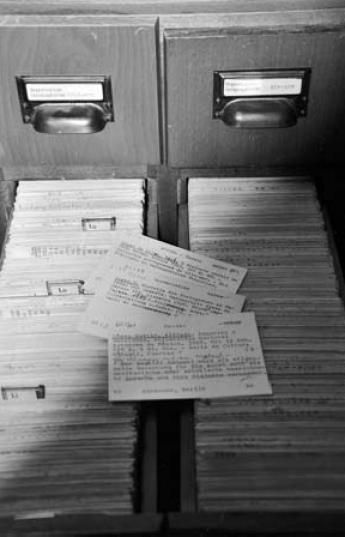

The database was set up on UNIX software so that, using an 800 number (still no Internet yet), people could dial in and either search it or get the matches that we found on a nightly basis. Because most dealers did not have computerized inventories, we had to do a lot of work to get the information about their books into our database. This was a problem, especially in the beginning when we needed to get the database started as soon as possible. The solution we came up with was to lease Xerox machines to use at the bookseller’s stores and to hire someone to photocopy the title pages of the books. The copies were then sent to India where the information was entered onto a disk. We uploaded the data from the disk when it was sent to us. It was a rather cumbersome process but worked relatively well.

Making uploading easy - both for dealers (to upload their inventories) and for libraries (to upload their wants) - was also a challenge. To do this, we had to develop our own software which had to be compatible with all the different computers and operating systems. Back then, there were many more options than Apple and Microsoft. There was also Bookmaster, probably the first dealer inventory program available, which was developed by Tom Sawyer. We struck a deal with him so that Bookmaster would be compatible with uploading to our database.

We had some successes such as selling a number of books to the Library of Congress that they had been looking for for many years. Dealers that used our database regularly found they liked it and saw their sales increase.

Competitors like AB Bookman vilified what we were doing, saying it would ruin the book business (though eventually they also tried using computers).

In 1993 Abacis went under. Looking back, I can see two main reasons Abacis failed. First we started too early. At the time, not enough dealers had computers and librarians were not willing to devote time to uploading their wants. Second, we expanded too fast, trying to do too much at once, and as a result, we spent much more money than our income could support. Our spending ballooned from the original, planned $750,000 to $1,500,000 in only a year and half.

As in any failed business there were, of course, internal problems. Karen was cut back to working only part-time because sales to the libraries were not going as well as expected. Clack Easter had been made president of the company because of his business background while Karen and I were made Vice Presidents. Both Karen and I had problems with how Clark Easter was running of the company, especially with his excessive spending. So we confronted him with our grievances; this did not go over well. Upon returning to the office after a sales trip to California in June of 1991, where I ran booths at several major book fairs, I was met by one of the vice presidents of Faxon. He told me I had ten minutes to clean out my desk and leave (this how corporate firings go). Clark had gone to Faxon behind my back and Faxon subsequently invoked a clause in our contract that said any of the owners (Clark, Karen or I) could be terminated without cause. Richard Weatherford was brought in to replace me.

Eventually, Abacis’s Maryland office was closed and all employees, except Richard Weatherford, were let go. The office was moved to Faxon’s headquarters in Massachusetts. Faxon had it own financial problems, which led to their eventual demise and to the closing of Abacis as well. After Faxon closed, Richard bought what was left and formed Interloc.

Interloc’s out-of-date computer system, high prices, and reluctance to allow the general public access to the database caused problems. Other database companies, such as ABE, eventually undercut Interloc. Interloc eventually changed its format to a website to remain competitive.

Convincing people to change over to new technology, no matter how useful, is always a struggle - Abacis’s failure is a prime example of that. Although it served a major need, book sellers and librarians alike were simply too reluctant to leave behind paper in favor of computer screens - they just weren’t ready for what we had to offer.

(Posted in the Oak Knoll Biblio Blog, published here by permission of Bob Fleck.)