Tip Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc.

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions: Poe and Rafinesque in Philadelphia

By Ken Giese

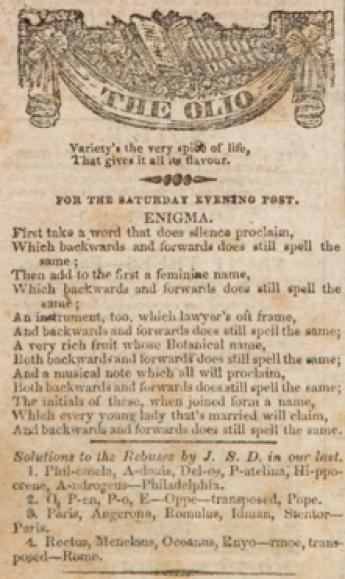

It is not often that one discovers the work of an overlooked or forgotten genius, or a previously-unknown work of an established master. This is, of course, the hope which moves us to carefully examine all sorts of periodical publications and ephemera. So when Tom Congalton asked me to catalog two large folio volumes of the Philadelphia-based Saturday Evening Post, from 1827 and 1828, I was pleased to find the puzzle poem “Enigma” attributed to Edgar Allan Poe, and “Psalm 139th” by his brother Henry Poe. Perhaps the most interesting contributions to these volumes are not the Poeiana, but rather a whole series of botanical sketches and other contributions by an eccentric genius with the evocative name Rafinesque. More on him further down. Here is the unsigned “Enigma,” from the March 10 issue of 1827 (see the picture).

By all accounts, Henry Poe might well have entered our collective-unconscious on the heels of his brother, had he not died at the age of 24 from tuberculosis and alcoholism. His collected poems were first published by Mabbott and Hervey Allen in 1926.

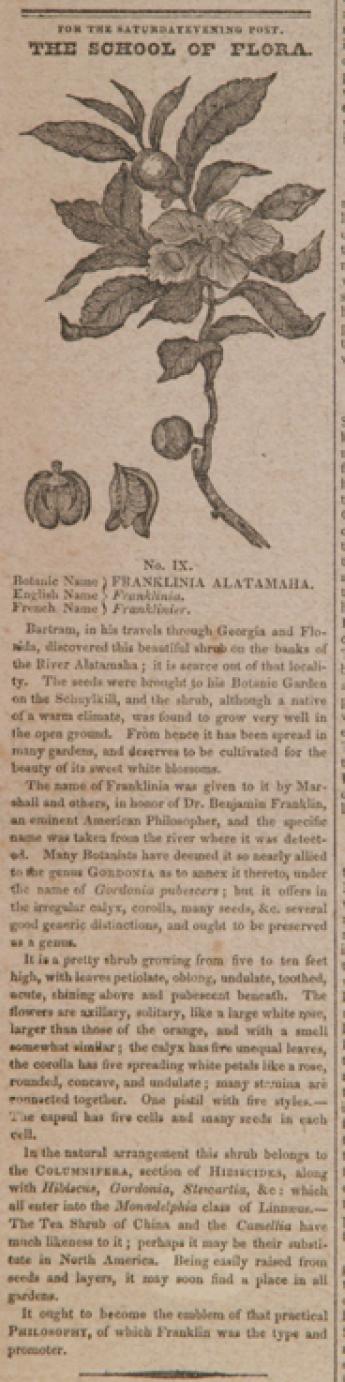

Each included a scientific description and a discussion of the species, which ended with the moral emblem, either adapted from an established “Language of Flowers,” or improvised by the anonymous author. Forty-two of these floral sketches were published throughout 1827, and a new series commenced in the January 19th issue of 1828, with an additional 22 sketches published throughout 1828. All were published anonymously, per the convention at the time, “For the Saturday Evening Post,” except the first sketch, printed in the first (January 6th) issue of 1827, which was signed “C.S.R.,” thus identifying the author as one Constantine Samuel Rafinesque. Here was a name that stirred my imagination, as did the beautifully-engraved flowers and their descriptions. This is sketch No. 9, “Franklinia Alatamaha,” named in honor of Philadelphia’s “great-souled” Benjamin Franklin, from the March 3rd issue, (published the week before an “Enigma”).

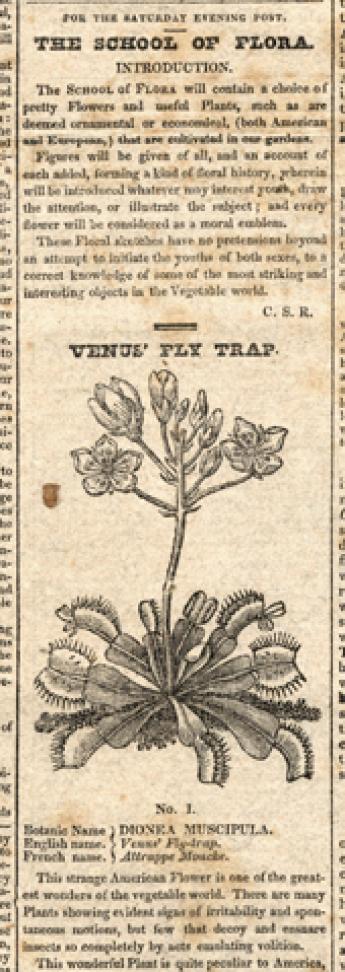

Discovered in 1765 by John Bartram, Philadelphia’s famous naturalist, on the banks of the River Alatamaha in Georgia, “this beautiful shrub,” writes Rafinesque, “deserves to be cultivated for the beauty of its sweet white blossoms.” After providing a concise, detailed history and description of this new species (not seen in the wild since 1802, but still flourishing today at Bartam’s Garden on the Schuylkill River), Rafinesque says “it ought to become the emblem of practical Philosophy, of which Franklin was the type and promoter.” It is likely that Rafinesque, a capable draftsman, designed the illustrated figures in the series, but I have not been able to identify the wood-engraver. Here is sketch No. 1, “Venus’ Fly Trap,” from January 1827, which includes an introduction to the series.

“This strange American Flower,” he writes, “is one of the greatest wonders of the vegetable world. There are many Plants showing evident signs of irritability and spontaneous motions, but few that decoy and ensnare insects so completely by acts emulating volition. …It has only been found wild in the swamps of North Carolina… [and] may be considered as a true emblem of Caution, teaching us to beware of deceitful attractions and the concealed snares of the world.”

Like Poe, Rafinesque was recognized by his peers as a genius. He made important contributions to botany, natural history, and philology. Born in Istanbul to a French father and German mother, Rafinesque lived throughout Europe, and first traveled to Philadelphia and Washington in 1802 at the age of nineteen, where he was received, respectively, by two of America’s founding fathers, Benjamin Rush and Thomas Jefferson. He traveled throughout Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia collecting botanical specimens, and also meeting with Indian tribes to study their languages. He developed a close relationship with Jefferson, partly in the unfulfilled hope of joining the Lewis & Clark expedition, before returning to Europe in 1805 with trunk-loads of specimens.

For the next ten years Rafinesque lived in Sicily, where he successfully pursued his scientific and business interests, and began publishing some botanical works. He eventually had two children, but could not legally marry their Italian Roman Catholic mother (Rafinesque being a Protestant). Nor perhaps was it likely he would have chosen to do so, as she was indifferent to his work. When she also proved to be unfaithful, Sicily thereafter became for Rafinesque a land of “perfidious men, deceitful women.” After their second child died in infancy, he resolved to return to the United States, and arrived in 1815 “naked and penniless,” his ship having been wrecked in Long Island Sound. All of his books and specimen collections from Europe and America were lost.

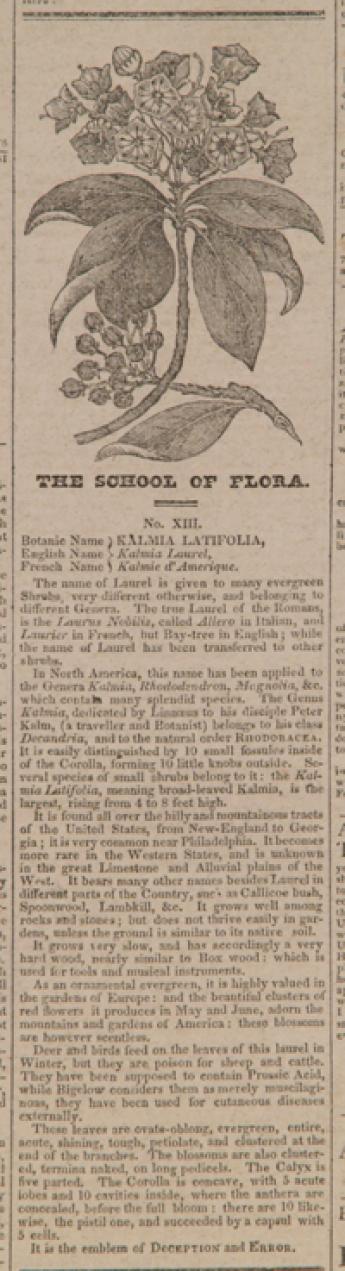

Back in Philadelphia, without formal employment, Rafinesque thus began publishing “The School of Flora.” It is perhaps not surprising that he chose to begin the series with “Venus’ Fly Trap,” as his wife (in all but name), after learning of his shipwreck in 1815, “promptly married a comic actor.” In fact, many of the sketches feature flowers of deceit. This is No. 13, “Kalmia Latifolia,” the emblem of “Deception and Error”.

In addition to the 64 botanical sketches published in 1827-28, Rafinesque contributed numerous other articles and short essays to the Saturday Evening Post, especially in 1828, which is the likely reason why he published fewer School of Flora sketches in that year. An excellent example of his pioneering work in Native American and Mesoamerican history and philology are his “Four Letters on American History. By Prof. Rafinesque, to J.H. M’Culloh, of Baltimore,” published in the June 7th, 21st, July 19th and September 6th issues of 1828. In this series of letters Rafinesque argues against the popular, pre-Darwinian belief that God had created the human races separately: “All the various systems and theories of monks and philosophers on the origin, climate, inhabitants, languages, &c. of America, have been repeatedly destroyed by facts… and yet they find many believers… To this day they speak of the Red men of America… while there is not a Red man, (nor never was) in this continent.”

Despite his many achievements - he published more than 6,700 binomial names of plants, and his theories of the gradual evolution of differing plant species through minute changes in response to environmental stimuli were acknowledged by Darwin - Rafinesque never did secure formal employment in his last fourteen years in Philadelphia. Like Poe, his last years were spent in poverty and ill-health, and he died “in a miserable garret” in 1840. His extensive unpublished manuscripts and large specimen collections were either destroyed or dispersed. His numerous published works have always been very scarce, since most were published in small editions at his own expense or with the help of friends.

According to a publisher’s blurb for the most recent biographical study of Rafinesque by Leonard Warren (2004), “Rafinesque displayed unique extravagance in his behavior, his imagination, and his lightning intelligence.” The blurb also recounts this telling anecdote: “Half a century after the death of Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1840, a small number of researchers, biographers, and historians of natural science suggested that the famed botanist’s last name should become the newest adjective in the English lexicon. Had they succeeded, ‘rafinesque’ would have forever been a literary tool to describe those poor souls, occasionally reaching but always aspiring to lofty heights, who brought chronic calamity and defeat upon themselves through grandiose, narcissistic visions of their own importance.”