Actualités Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Books Tell You Why, Inc.

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Famous Literary Hoaxes (Part One)

By Joachim Koch

Literary critics frequently argue that literature is full of frauds; there are plenty of authors, after all, whose work offers little substance or artistry. But the world of letters also has its share of true frauds: cheats, liars, and forgers. In some cases, these individuals were merely mischievous pranksters, but in others they hoped to profit from their malevolent handiwork. Here's a look at some of the biggest literary hoaxes of all time.

A Forgery of Epic Proportions

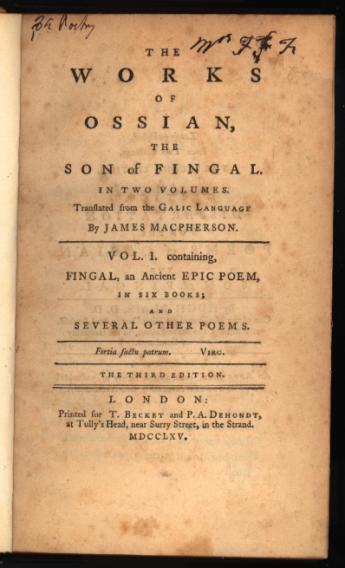

In 1760, Scottish poet James MacPherson came forward with a magificent work: a series of epic poems he'd collected from ancient sources. The works, now commonly called the Ossian poems, were an instant international success. They also sparked considerable controversy. Irish nationalists claimed that MacPherson's sources had been Irish, rather than Scottish. And the work's authenticity was impossible to determine. Samuel Johnson, never afraid to share his opinions, vociferously argued that MacPherson was "a mountebank, a liar, and a fraud." He went on to insult the poems' quality, calling them "as gross an imposition as ever the world has been troubled with." Hugh Blair refuted Johnson's allegations in A Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian (1763). Starting in 1765, his essay was included in editions of the poems to lend credibility. Great thinkers like Thomas Jefferson and Diderot praised the work, while Voltaire satirized it.

Three years later Gaelic scholar and Irish antiquarian Charles O'Conor backed up Johnson, ruling the poems forgeries. He later expanded the theory into a book. The Committee of the Highland Society made an inquiry into the matter, but reached no definitive conclusion; the debate persisted into the nineteenth century. It wasn't until 1952 that Scottish poet Derick Thomson concluded that MacPherson had indeed collected Gaelic ballads - but he'd also made substantial changes to the original works and added many of his own verses and poems. Though the Ossian poems are no longer accepted as ancient Gaelic epic, they are still studied as a magnificent work of imagination by MacPherson.

Bogus Manuscript at the British Museum

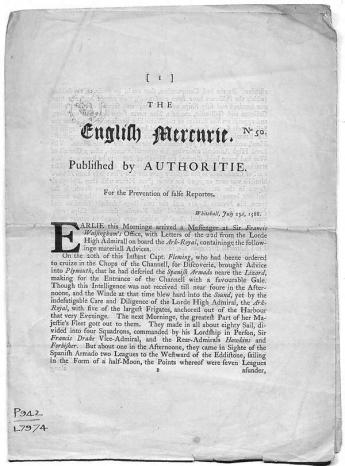

Mercurius Gallobelgicus was published in Cologne, Germany in 1594. It's long been accepted as the first newspaper. But in 1766, Dr. Thomas Birch shook scholars' conviction in that fact by donating an unusual set of documents to the British Museum without any explanation of their origin. He'd bequeathed a manuscript and two printed copies of The English Mercurie , dated July 23, 1588. The newspaper detailed the English battle with the Spanish Armada. The typeset, spelling, and other factors led people to accept the document as real; Scottish antiquarian and political writer George Chalmers even cited The English Mercurie in his 1794 book The Life of Thomas Ruddiman.

The authenticity of The English Mercurie remained unchallenged for almost fifty years. Then in 1839, Thomas Watts stumbled upon the original manuscript in the archives of the British Museum. He compared it to other examples of Birch's correspondence - and realized that the handwriting precisely matched that of Birch's friend Philip Yorke, second Earl of Hardwick. The two had apparently created The English Mercurie as a literary game. Though the work is widely known to be fake, it's still mistakenly taken for a factual account on occasion.

A Questionable Use of Genius

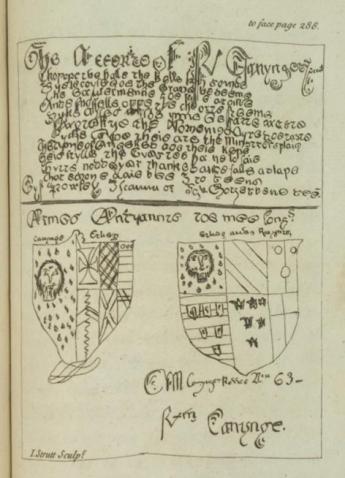

Thomas Chatterton revealed great literary promise from a young age: the Bristol-born lad was writing poetry by age eleven and was apprenticed to a lawyer at age fourteen. Contemporary writers were surprised and delighted by his talent. Chatterton also happened to have access to a chest of historical documents for his parish - which meant a ready supply of ancient parchment. He soon hatched a plan to use these paper scraps for his own entertainment and ends. Chatterton produced a few manuscript poems, claiming they were the work of fifteenth-century monk and poet Thomas Rowley. Local antiquarians were thrilled to learn of a previously undiscovered literary hero. Young Chatterton took the deception a step further, submitting a few Rowley poems along with his own to Town and Country Magazine. Only one Rowley poem was published there during Chatterton's lifetime, in May 1769.

He also saw the poems as a means to gain the patronage of Horace Walpole, whose wildly successful Castle of Otranto (1765) had supposedly been translated from a "found" manuscript." Walpole initially encouraged Chatterton, but he soon changed his tune. He pronounced the Rowley poems to be forgeries, publicly humiliating Chatterton. Not everyone took Walpole's side, however, and Chatterton still had plenty of fans. But plagued by depression, health problems, and poverty, Chatterton poisoned himself in August 1770. He was seventeen years old. Seven years later, a collection of Rowley poems was published, meeting both enthusiasm and skepticism. In 1778, Thomas Wharton authoritatively ruled the poems forgeries in History of English Poetry. But it wasn't until the nineteenth century that the Rowley poems were accepted as Chatterton's own work. By that time, Chatterton had become an icon of the Romantic movement. John Keats dedicated "Endymion" to Chatterton's memory, and William Wordsworth called Chatterton "the marvelous boy."

Stay tuned for the next two installments of Famous Literary Hoaxes!

(Posted on Books Tell You Why, presented here by permission of the author.)