Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Tavistock Books

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Charles Dickens Debt to Henry Fielding

By Vic Zoschak

When Charles Dickens’ sixth son was born on January 16, 1849, the boy was named for one of Dickens’ favorite authors. Supposedly Dickens had first thought to name the boy after Oliver Goldsmith, but he feared the child would be ridiculed as “Oliver always asking for more.” Instead he named his son Henry Fielding Dickens, after legendary 18th-century author Henry Fielding. Though Dickens was born too late to meet Fielding, his predecessor had a profound impact on Dickens’ work.

A Father of the Novel

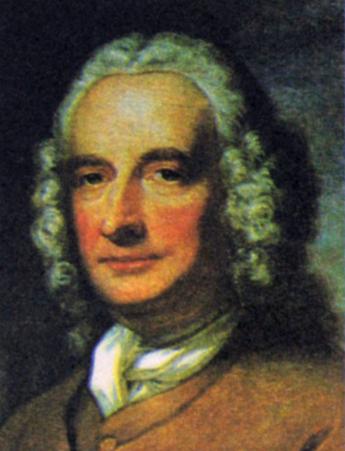

Henry Fielding (April 22, 1707-Oct 8, 1754) began his literary career due to financial distress. At the time writing plays could be quite lucrative, so Fielding turned his attention to drama. His first play, Love in Several Masques (1728), was an immediate success, and over the next several years Fielding would write at least 25 more plays. Most of these had little literary merit. In 1736, Fielding wrote Pasquin, a Dramatic Satire of the Times, which was performed 60 times in only three months. The play attacked the administration of Sir Robert Walpole, portraying the government as rife with corruption.

Fielding followed with The Historical Register for the Year 1736 (1737), which was even more critical of Sir Walpole’s administration. The play was so overtly critical that it caused worry among government officials. Sir Walpole seized the opportunity to pass the License Act of 1737, turning over control of the theatre to Lord Chamberlain. After that, it was virtually impossible to produce a satirical play, and Fielding found his career as a dramatist at an abrupt end. Though Fielding turned back to the law to make his money, he soon found himself facing financial trouble. He began editing the anti-Walpole The Champion, or British Mercury (1739-1741), writing under the pseudonym Captain Hercules Vinegar.

Then Samuel Richardson published the first two volumes of Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded in 1740. Fielding found Richardson’s tone so self-serving and moralistic, he was moved to pen a scathing satire of Richardson’s novel. An Apology for the LIfe of Mrs. Shamela Andrews (1741) was published anonymously, but is accepted as Fielding’s work. He followed up with the comic romance of Pamela’s brother in The History and Adventures of Joseph Andrews (1742). Both novels were quite successful.

Fielding, as many know, also had a very successful career as magistrate, being, for example, co-founder of London’s first police force, the Bow Street Runners. But he never stopped writing. He was a prolific writer of political pamphlets. Vehemently anti-Stuart, Fielding wrote for the burlesque Jacobite Journal (1747-1748) as a response to the Jacobite uprising of 1745. That event would later serve as the backdrop for The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749). It was with this novel that Fielding made his greatest contribution to literature: this picaresque tale blends elements of the mock epic and comic romance, but it also introduces the omniscient narrator.

Meanwhile the novel’s protagonist, Tom Jones, is an ordinary person, a sort of modern-day everyman. With the figure of Tom Jones, Fielding made the novel accessible and interesting to a whole new middle-class reading public. It’s no surprise, then, that a copy of Tom Jones found its way to the bookshelf of the poor Dickens household when Charles was a boy.

Fielding’s Impact on the Victorian Novel

While Richardson is credited with originating the psychological realism so prevalent today, Fielding was the inventor of a new narrative voice that vastly influenced Victorian writers from William Makepeace Thackeray to Charles Dickens. Indeed, Dickens owes quite a debt to Fielding. Dickens’ first several novels were picaresques (novels of short episodes), a style he’d picked up from the books of his childhood–namely Arabian Nights, Don Quixote, and Tom Jones. Dickens would also incorporate elements of the mock epic and the comic romance in his stories.

Dickens also followed in Fielding’s footsteps by using fiction to openly address political and social issues. Fielding made literature more egalitarian; while the novel had previously focused on members of the upper classes and their lives, Fielding opened up the genre. Dickens furthered that work with tales like Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol.

Fielding’s novels surely left a lasting impression, influencing Dickens for a lifetime. It’s no wonder that Dickens chose to name a child after Fielding.

Where else do you see Fielding’s influence on Dickens’ writing? And which writer would you choose for a child’s namesake?

(Posted on the Tavistock Books Blog, presented here by permission of Vic Zoschak.)