What a 19th-century sex guide tells us about the evolution, stasis of Western norms

By Kristin Masters

On Valentine’s Day we celebrate a holiday of love, commitment, chocolate… and 19th-century norms on reproduction and dating?

Yes, the 1800s: A reminder that sex wasn’t always fun or accurate.

And there’s no better antiquarian book to savor on Valentine’s Day than ‘Physiological Mysteries and Revelations in Love, Courtship, and Marriage; An Infallible Guide-Book for Married and Single Persons in Matters of the Utmost Importance to the Human Race’ (1842).

Now say that three times fast.

Commonly referred to as “Becklard’s Physiology,” by French physiologist Eugene Becklard, the self-help guide for Victorians tackles topics such as sexual frustration or disfunction, and offers a quaint, enlightening, and often hilarious glimpse into the era’s knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and sexuality. Becklard delves into all the controversies of his day, illustrating not only his own wide reading, but also the shortcomings of medical knowledge well into the mid 1800s.

Little is known about Becklard, save what he says about himself in his book. He notes in the preface that, “I can scarcely be called an officious or upstart medler (sic) in the mysteries of physiology, insomuch as I have studied it with unremitting attention for nearly thirty years.”

A hint of innuendo, perhaps? Becklard also promotes his extensive experience at a “lying-in [maternity] hospital,” that he believes gives him additional authority to write about issues of conception, pregnancy, and childbirth. Like his contemporaries and centuries of scientists before him, Becklard grappled with the mechanics of the Problem of Conception. The woman’s role in conception seemed nebulous, as scientists had no external evidence of ova, as they did of spermatozoa; Leewenhoek, the “father of microbiology” had discovered sperm in 1677, a discovery that challenged the concept of spontaneous generation held so dear in Christian doctrine. Becklard acknowledges that finding and notes that

“It has been denied by many able physicians that the female secretes any seminal fluid, which if true, would give her but little to do with the business of reproduction….In fact it has been ascertained beyond question that the female does indeed secrete a prolific fluid (and) there is nothing more certain than that each [parent] has to furnish about equal parts of the embryo” (p 107-8).

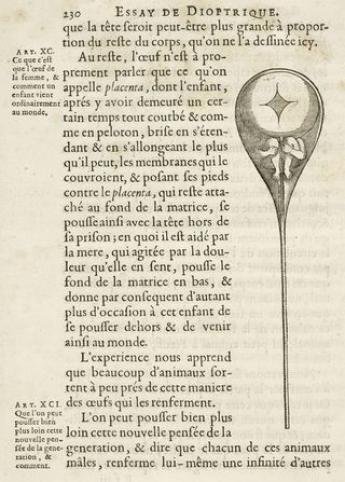

A progressive stance indeed - one that Becklard soon undoes. He brings up the theory of homunculus (Latin for “little man”), the idea that the male sperm contains a preformed human being simply waiting to be implanted into the woman’s womb and grow into a person. Though the concept had existed for centuries, the term “homunculus” was first used by Paracelsus, a sixteenth-century alchemist, in his ‘De natura rerum’ (1537). Né Phillip von Hohenheim, Paraclesus claimed to have created a homunculus from sperm alone, and he describes the process: “Let the semen of a man putrefy by itself in a sealed cucurbite with the highest putrefaction of venter equinus for forty days, or until it begins at last to live, move, and be agitated, which can easily be seen.” The homunculus then must be carefully fed “the arcanum of human blood” and nurtured for forty weeks, like a real fetus (p 175).Jan Swammerdam summarily discounted the preformation theory back in 1669, when he demonstrated the epigenesis of insects in ‘Historia Insectorum Generalis.’ The theory had since gained steam, but not enough to debunk the homunculus for good; Becklard observes that the concept that “the embryo was a perfect living being furnished exclusively by the male parent, has never been set aside by proofs to the contrary. In fact, it cannot be denied that animalculae [sperm] formed like tadpoles exist in the prolific fluid, which it seems possible may be human beings in utero” (p 116).

By Becklard’s day, the homunculus had come back into fashion–in the world of fiction. Laurence Sterne famously satirized “homunculists” in ‘The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman’ (9 vols; 1759-1767). In the eighteenth century, medical professionals searched for a means of baptizing babies in utero, so that stillborn children could still go to heaven, an absurd proposition, but one that truly concerned parents. Tristram Shandy “begs to know, whether after the ceremony of marriage and before the time of consummation, the baptizing of all Homunculi at once, slapdash, by injection, would not be a shorter and safer cut still” (p 63). Shandy slips into the more delicate French to explain the procedure, which he suggests could be performed “par le moyen d’une petite canulle, and sans fair aucune torte au père” (p 64).

The homunculus also reemerged in Gothic literature, most notably in ‘Faust’ (1832) and ‘Frankenstein’ (1878). In ‘Faust, Part 2,’ Goethe features an alchemically created homunculus that represents a perfect soul ready to be born. It’s the ideal foil to Faust himself, who longs to escape his physical body to become a clean soul. Frankenstein’s monster is born from a homunculus, and Mary Shelley likely drew inspiration for Victor Frankenstein’s character from the figure of Johann Conrad Dippel, an alchemist who was born in Castle Frankenstein and reputedly stole corpses for medical experiments.

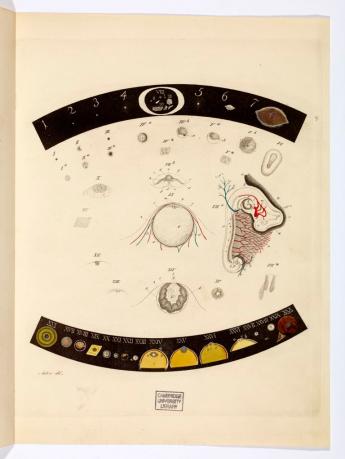

So perhaps we can excuse Becklard’s subscription to the homunculus theory. But there’s one caveat: the mammalian egg had been discovered in 1827–almost two decades before Becklard wrote his Physiology. Karl Ernst von Baer offered detailed (and quite beautiful) sketches in ‘De ovi mammalium.’ Baer presents not only the human egg, but also the eggs and embryos of other animals for comparison. Becklard’s own indecisiveness shows, however, that he’s not entirely unwilling to weigh scientific evidence; he is truly a man caught in the middle, struggling to reconcile his own observations with new discoveries that he cannot necessarily replicate or witness on his own. We can choose to interpret Becklard as a fool…or as a healthy skeptic.

The length of Becklard’s career at the time of publication gives the reader an idea of when he went to medical school. He likely would have finished medical school relatively early in the nineteenth century–before many innovations of the century. Indeed many of his perspectives seem decidedly “old school,” as if he has chosen to ignore emerging research and innovation. That said, Becklard was obviously quite well read. He consistently alludes to numerous great thinkers both contemporary and ancient, from George Sand, Dominque Jean Larrey, and Thomas Malmud, to Jan Swammerdam, Anton van Leewenhoek, and Dioscorides.

Lest we dismiss Becklard as both quack and hack, we must consider the context of his work. Charles Darwin had yet to write ‘Origin of the Species’ (1859), a work that would revolutionize the way scientists viewed humans as organisms. In Becklard’s day, people were seen as distinct than and superior to other animals because they possessed an immortal soul. Darwin’s work turned that notion on its head, and it was only then that scientists really began to see humans as objects of scientific observation.

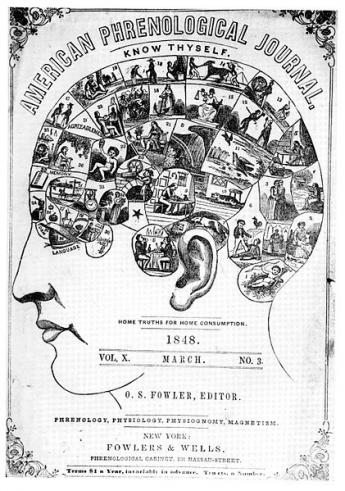

Meanwhile, phrenology was all the rage. Numerous reputable scientists promulgated the theory that the shape of one’s cranium indicated one’s personality, aptitude, and even morality. Doctors still subscribed to the concept of the four humors and used techniques like blood letting and placing hot cups on the body to balance the bodily fluids. Thus, though Becklard lived in a time of great discovery, he also lived in a period where scientists and medical professionals still had plenty to learn. Hence we can’t completely blame Becklard when he make statements like

“it is necessary to beauty that a woman’s pelvis be well developed; and it will be well for the man who marries a woman with a contracted one to be diminutively organized in his corresponding functions” (p 105).

Nor can we too harshly criticize Becklard’s proclivity for offering one panacea for virtually all sexual ailments. His drug of choice, Lucina Cordial, was more formally known as “Dr. Magnin’s Lucina Cordial, or the Elixir of Love.” Becklard wholeheartedly recommends this formula: “Within range of my own practice, I could cite at least one hundred cases, in which the Lucina Cordial has been administered to the most eminent success, and a number of my medical friends bear equally decisive evidence of its worth” (p 28). Becklard never reveals the cordial’s ingredients, but he does recommend it for every ailment from impotence to lack of libido.

Glimmers of Progressivism

Becklard puts forth plenty of antiquated views (the purpose of a sex drive, he says, is “supplying other worlds with spiritual inhabitants”), but he also takes multiple risks by setting forth several progressive ideas (p 18). The very existence of his book is revolutionary, especially as Becklard strongly urges parents to share it with their children age ten and older. Although Victorians weren’t frigid regarding sex, they also didn’t talk about it. The character of Mrs. Grundy in Thomas Morton’s play ‘Speed the Plough’ (1798) even came to personify the censorship of the era. Becklard, therefore, shows himself a bit of a rogue, shamelessly extolling the medical benefits of sexual education.

More fascinating is Becklard’s endorsement of divorce in cases of sexual incompatibility.

“After all, it’s not to be expected that much [conjugal] happiness can attend the union of a lymphatic man with a sanguine woman, and vice versa” (p 66).

Alas, few copies of the book survive–it’s not the kind of book that readers would have striven to preserve, as most people probably read it in secret and disposed of it the way modern readers do with ‘Fifty Shades of Grey.’ But several institutions have copies in their holdings. Rutgers University in New Jersey has a copy dated 1850, indicating that the book enjoyed enough popularity to warrant multiple printings. Fortunately for us, Google has made the title available in a free ebook.

Be sure to peruse its worn pages if you’re looking for a little perspective (and a sigh of relief) about sex, dating, and courtship today.

Sources

Becklard, Eugene. Physiological Mysteries and Revelations in Love, Courtship, and Marriage; An Infallible Guide-Book for Married and Single Persons in Matters of the Utmost Importance to the Human Race. Trans. Philip M. Howard. New York: Holland and Grover, 1842 (© 1844, misprint)

“Books and Babies: Communicating Reproduction.” Cambridge University Library. 7 July-23 December 2011. http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/exhibitions/Babies/index.html (12 Feb 2013)

Paracletus. De natura rerum. From: Paracletus: Essential Readings. 1537. Trans. Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1999.

Sterne, Laurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. 1759-1767. London: W. Wilbur Head, 1803.

Special thanks to Vic Zoschak of Tavistock Books for his insightful guidance on this article.

(Posted on berlinSCI, presented here by permission of the author. Kristin Masters specialises in marketing for the rare and antiquarian book trade. Her literary interests include 18th century British literature, antiquarian scientific texts, and modern first editions. Kristin Masters holds a degree in English from the University of Florida, where she conducted research and edited the Scriblerian and the Kit-Kats (Smollett, Sterne, and Pope) under the supervision of Dr. Melvyn New, editor of the Florida Edition of ‘The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.’)