Tom Congalton

By Barbara van Benthem

How many books do you have?

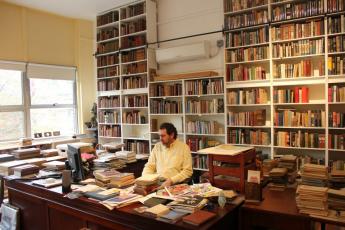

Currently I have just short of 250,000 books catalogued and offered for sale. Of these perhaps 25,000 of them would be considered more or less collectible. The rest tend to be just good used books. Aside from that, I have perhaps 100,000 books that have yet to be catalogued.

Why so many?

I was hoping that you could tell me! In truth, like many booksellers I have dealt in a wide range of material for many years, including used and not-particularly-valuable books. While most of my income derives from my more expensive books, having a large inventory does allow us to “mine” the material for large subject catalogs. We have occasionally managed to engage collectors with less expensive books, only to find out that they were also willing to buy more expensive material. Also, dealing in large numbers of books provides us with the infrastructure and flexibility to acquire large libraries that might seem overwhelming to other booksellers. There is seldom much competition for truly large libraries, which can result in advantages when we buy.

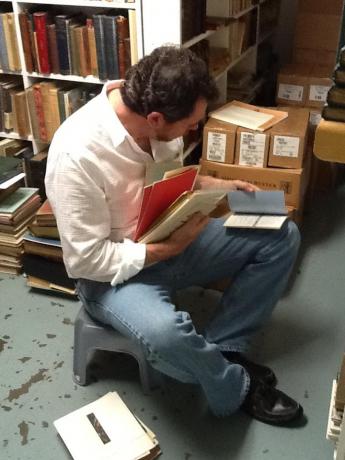

Back to the beginnings. How did you become involved in the rare book business?

I was a collector since I was 16 years old. I was also reasonably omnivorous, so would buy books in a wide variety of categories, and early on started quoting books to dealers through the mail. When I was in my early 20s I started a cabinetmaking company – I was a pretty uninspired cabinetmaker, frankly – but continued to accumulate books and continued to sell to or trade with dealers to enhance my own collections. I started to get serious about it in my mid-20s, but didn’t classify myself as a fulltime bookseller until I was about 32.

In the late 1970s I met Chandler Gordon of the Captain’s Bookshelf in Asheville, North Carolina, who had a general antiquarian shop with a specialty in American Southern literary first editions – probably one of the reasons that I sort of have a residual specialty in that subject. We did a lot of business when I was in my scouting phase. Through him I learned about other first edition dealers including Quill and Brush, Ken Lopez (who I later became an unofficial partner with and we remain friends – often sharing booths at book fairs), and many others. Over the years I’ve become friends and often partnered on books and libraries with many other booksellers. One irony is that as time goes by, I’ve tried to learn new tricks from the different and innovative paths developed by some younger booksellers, and while it might be a stretch to call them mentors, my evolving business model has sometimes been influenced by booksellers who are barely in their 30s or 40s.

I started as a general bookseller, but eventually became a specialist in American and English literary first editions, mostly because dealers in that specialty were the dealers that I first interacted with. While I still have a very strong inventory in that subject, I have sort of come full circle. I’ll deal in any interesting books that come my way. In the course of this journey, I’ve developed specialties or sub-specialties in African-American history and literature, sporting books, particularly baseball, drama and plays, genre fiction such as detective fiction and science fiction, early 20th century romance novels in dust jackets, and music and counterculture.

As befitting my category as a dealer in modern books, I’m particularly interested in dust jackets – something many of my European colleagues often seem less interested in. In pursuing that interest I have compiled what I believe is the largest private collection of 19th century books in original printed dust jackets.

Do you remember the most extraordinary book you ever sold or bought?

I’ve sold many wonderful books, manuscripts, and archives, but frankly, I’m always more interested in the next one that I’m going to sell. That’s what so great about being a dealer. My job is buy rare books every day, while collectors have to be more careful of their resources.

And the most extraordinary book you ever missed?

The most extraordinary book I ever missed wasn’t a book. I attended an auction in Pittsburgh and ended up bidding on two daguerreotypes – one of Frederick Douglass, another mis-identified as an obscure Philadelphia author but that turned out to be of John Brown. I thought I’d buy them easily as I was willing to far exceed the estimates of a few hundred dollars each. One went for about $12,000 and the other around $24,000, and I stayed on them nearly all the way but didn’t get them. It turned out that within a year, one sold for around $200,000 and the other sold for $129,000. Oh, well!

What about your first catalog?

My first catalog is ironically now something of a rarity. I typed it on a cheap dot-matrix typewriter, gave it to a fledgling local “quick” printer, and it came back virtually unreadable. I sent one copy to Chandler Gordon who sent it back with comments, one of which was “I’d never send anything so ugly out with my name on it”. I had hand addressed about five copies – with my typical forethought, I didn’t actually have a mailing list to send the catalogs to. When I received Chandler’s critique, I threw the five copies in my desk, and put the rest into a storage shed until I could think about it. The shed promptly burned down, making the five copies in my desk the only existing copies. I hope that the catalog wasn’t so bad that it caused spontaneous combustion, but it’s a possibility. I was too depressed to do another catalog for about a year, at which time I had finally declared myself a fulltime bookseller.

One of my most interesting and successful catalogs was my first catalogue of early to mid 20th century romance novels in original dust jackets. These were novels, mostly “women’s fiction”, that were probably considered below the threshold of literary excellence that most libraries thought worth preserving, and thus were objectively very scarce. There were about 500 books in it, and two different institutions bought over 100 books each. A third just called and said something on the order of “just pick out a hundred and send them along”! While it wasn’t my most successful catalog from a financial standpoint, it might have been the most gratifying.

Your biggest failure?

I can think of a couple. I once did a full color catalog of pre-WWII American western cowboy novels in dust jackets, thinking that institutions would want to fill in what is arguably one of the only true “American” genres, but I received very few orders. Curiously one regular collector, mostly of serious Russian fiction, ordered item number 1 in the catalog because he had never read a western novel before and thought he might try them. A week later, he ordered number 2, and then number 3, and then number 4. When he got to number 5, I made some facetious remark about hoping that he would read his way through the whole catalog. I think he took offensive at my levity, and he never bothered to order number 6 or any other westerns. Note to self: “don’t make smart remarks when people are buying your books.”

On another occasion I found a website that listed the names and addresses of every individual who had given the maximum amount of money allowable in the American Presidential election in 2004, I think it was. I thought, “if these people have enough disposable income to give the maximum amount of money to a political campaign, at least some of them must care enough about books and ideas to buy some books”. We created an elaborate full-color catalog with a wide variety of material, mostly more expensive books. We sent out something like 10,000 copies and received exactly one order: and it turned out to be from one of our regular customers who just thought it was one of our regular catalogs. Happily, it was a big order and more than covered the costs, but it still wasn’t my brightest idea.

Book fairs?

Book fairs are hard work for dealers, and they can be tedious, but there is nothing like the opportunity to be able actually compare and handle rare books in person.

Book collecting can be a two dimensional activity when pursued online, but it’s in person where it becomes exciting. Plus being exposed to the odd and sometimes wonderful personalities and characters in the book world – dealers, collectors, and librarians, can be worth the price of admission itself.

What is the secret of your success?

The secret of my success is never thinking I’m successful. I’m always trying to motivate myself to look for new material or better yet, new types of material to sell. I want to try to expand the boundaries of what the collectors and libraries I deal with are looking for, and hopefully to do it before someone else does it.

We’ve had a number of shops over the years, and while they have been reasonably successful, they don’t allow me to concentrate on my core of collectors – private collectors and librarians who are not in easy geographic proximity to me. For the time being our shop presence is limited to exhibiting books in cooperative shops in Newcastle, Delaware and Tokyo, Japan.

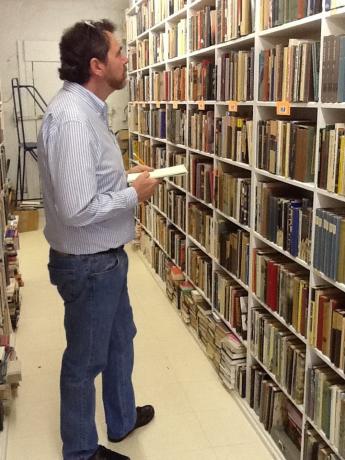

We issue catalogues very aggressively, probably at least one full-scale catalog per month, plus dozens of “mini-catalogues” devoted to individual subjects or authors that we prepare in advance and include with orders. These mini-catalogs often result in follow-up sales, and hopefully, to a continuing relationship with collectors. We have nearly a quarter of a million books online and sell a large volume of books that way every day, including occasionally, very expensive books. However, we view the internet as a passive way to sell books – we throw the books out there and wait for someone to buy them. Our catalogs are a more aggressive method of selling books. When you get a catalog you have to move fast or risk losing what might be unique item.

Obviously the internet has affected our definition of what is scarce or rare – books that enjoyed a modest regional scarcity might have been saleable at a premium to a local collector, but now all of those “local rarities” are probably all on the internet together and don’t look so rare. This has caused something of a disconnect between used booksellers with open shops and “antiquarian” booksellers. These used booksellers were a traditional source for rare books, when they would occasionally find a scarce or rare book in their shops and feed it into the antiquarian market to a specialist dealer. As open shops closed this traditional source has dried up. However, the internet has reinforced that some books are indeed rare, and it has also expanded the potential market for those books exponentially. Every day we sell dozens of books overseas – a market we’d have had very little chance to engage with before.

Obviously information technology has changed very quickly, and will continue to do so. I’m not sure I’d “blame” the internet for changes in the rare book trade. The Internet giveth and the Internet taketh away. The booksellers who aren’t too busy complaining about the Internet are finding ways to use it to their own advantage.

You have been involved in the activities of the ABAA, ILAB, Rare Book School and other organizations of the rare book trade for a long time. When did you start?

The Rare Book School experience is pretty wonderful, and I suggest if one wants to get deeply immersed in one or another of the many aspects of rare books, it’s worth the trip. I’ve co-taught a course with Katherine Reagan, the Curator of Rare Books at Cornell, at Rare Book School in Charlottesville for the past five years. Then director Terry Belanger, noticed that there were no booksellers on the faculty – mostly librarians and academics, and solicited Katherine’s opinion for a dealer to help with a new course. Even though I had only met Katherine twice, for brief periods of time, we shared enough of a common aesthetic that, after some initial fumbling around, we’ve managed to create what seems like a successful course. This year, not content with success, we’re developing a new course with a third instructor – a donor/collector – and we will attempt to examine and navigate the interaction of rare materials in the trade between dealers, collectors, and librarians.

Soon after I joined the ABAA there were some problems with the success or failure, or even possibly the continuation of the New York Antiquarian Book Fair. The number of exhibitors was languishing around 100 and there were some doubts about the future of the fair. Because I was in some proximity to New York, I was asked by the Board of Governors to become the co-chairmen of the fair. The national book fair chairperson Priscilla Juvelis, had recently hired a different promoter, Sanford Smith, and I’ve worked with Sandy for almost 20 years now on the fair. For the past several years we’ve been sold out with a waiting list, and over 200 dealers participating. After that I was elected to the Board and successively became Secretary, Vice President, and from 2000 to 2002, President.

As ABAA President I had attended a couple of ILAB Presidents’ Meetings and attended some Congresses. When Bob Fleck’s term as ILAB President ended, he recommended me as a potential member of the Committee, and I was elected to the Committee in 2006. In 2010, I was voted as Vice President. First, I was editor of the Newsletter, and was and still remain head of the Internet Committee.

My participation has reinforced to me how important it is to take advantage of the international contacts and collegiality that can result from these contacts. I believe that ILAB Congresses and international contacts have always been valued in a world where the means of communication were expensive and infrequent – expensive travel, expensive telephone calls, etc. Obviously, with email and cheaper travel, we see or communicate with each other much more frequently now. The Congresses, which used to be the only real way to get together with international colleagues in a social setting (outside of the slow hours of book fairs) have been seen as an anachronism by some. I think that while that’s understandable, it is also short sighted. I think in an “industry” that is evolving as quickly as ours these face-to-face contacts are valuable for the frank exchange of information that doesn’t always result from emails. Those who have attended multiple congresses generally tend to agree.

Amor Librorum Nos Unit – our motto – “the love of books unites us” pretty much says it all. It’s a revelation to travel half way around the world to meet with others who face the same challenges that I do on a daily basis. The rare book world is relatively small and highly idiosyncratic. I think that what we do – the aggressive preservation of culture that has an effect that greatly transcends the size of our industry, is enhanced by these contacts. One practical example is the networks we have created to track and recover stolen books. Our small and modestly funded organization can do as much to contribute in this area as much larger international law enforcement agencies.

Why would you never miss an ILAB Congress?

I missed one when I broke my arm playing basketball, effectively ending my basketball career – not that anyone noticed. Other than that I’d make every effort.

One of the wonderful things about Congresses is that you never really know what is going to interest you. In Scotland, bagpipers and drummers emerging from the mist late at night after a long dinner provided some unexpected magic to the event. In Madrid, a maybe too-late dinner at a flamenco restaurant – an entertainment I thought I had less than no interest in, turned out to be unforgettable. In Lucerne, taking a coach up to a mountain church - really, another church? – sounded dull, but the setting and musical presentation were fantastic and not to be missed; and that doesn’t even include the dinner in a cave tucked behind a waterfall.

What do you think about the future of our business?

Everyday I meet people, both young and old, who are fascinated by what we do for a living. Rare book collectors have always been a very narrow slice of the population. I think the Internet has broadened our market and that market will develop greatly over the next decade or two. Booksellers will have to learn new tricks, develop new specialties, and utilize technology to broaden their markets. Collectors will develop as they always have – perhaps encountering a random book or object that attracts their attention, looking into it further, and eventually pursuing the objects of their desire – in some cases objects that they hadn’t even known existed.

I’m really very optimistic over the future of book collecting, although those who want it to function in the exact same way that has in the past couple centuries are probably going to be disappointed.

Here, ILAB can do a lot. We can continue to preserve the ethics and professionalism of our members – the things that make us the obvious portals for objects of rarity to collectors, libraries, and scholars. We can encourage the collegiality that allows our members to network with each other in order to help build collections that enhance our knowledge of both the past and the future. We can challenge ourselves and our collectors to use our imaginations to expand the boundaries of traditional book collecting. Some of my colleagues are selling archives of authors and scholars that consist almost entirely of computer data!

The more things change, the more they remain the same.