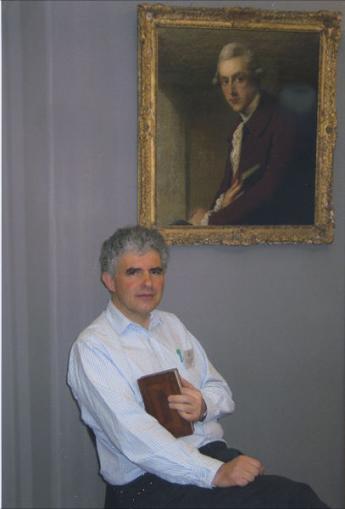

Michael Silverman

By Sheila Markham and Robert Bartfield

Michael Jeffrey Silverman, dealer in literary and historical manuscripts, was born on November 7, 1949. He died of a stroke on May 12, 2011, aged 61.

With the untimely death of Michael Silverman, the world of literary and historical manuscripts has lost one of its most respected dealers, and the antiquarian trade in general a much loved and popular colleague. Internationally acknowledged as a dealer of great integrity and expertise, Michael wore his knowledge lightly. He liked to affect an air of mild indifference to the exceptional material that often passed through his hands. His self-deprecating style, so far removed from that of the hustling businessman, was much appreciated by the many collectors, private and institutional, who responded to the good manners that informed his dealings as a whole. In 2008 Michael was justly proud to be elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. Earlier this year he was honoured to be invited by Michael Meredith to talk about manuscript-collecting to the boys at Eton, to whom he gave a characteristic piece of advice not to bother with Keats unless they had a lot of pocket money.

Regarded as a model of their kind, Michael’s catalogues contained fastidious descriptions of thoughtfully chosen material, meticulously researched, and beautifully presented. Published in 2010, Catalogue 28, entitled One hundred Select Manuscripts, was to be his last catalogue. Full of original and engaging material, it is a perfect illustration of his interests and expertise. The descriptions reveal his ability to evaluate the significance of a letter and to place it in its proper context – a skill which depended on the patient accumulation of biographical, historical and miscellaneous information, in order to arrive at an informed appreciation of the material. Michael combined formidable scholarship with a sound financial grasp which enabled him to strike the difficult balance between competing factors such as rarity, interest of contents, and the many other considerations that ultimately determine commercial value. Described by James Fergusson as ‘a catalogue to read and keep’, Catalogue 28 has been widely acknowledged as the high-point in his achievement as a dealer in literary and historical manuscripts.

Michael Silverman was born in Leeds in 1949, and grew up in the leafy suburb of Alwoodley. His father owned a wholesale cloth business in North Street. Michael was educated at Leeds Grammar School where he excelled academically. A considerable classical scholar, Michael was also a keen sportsman. He liked to play football wearing Pelé’s number 10 shirt, and cricket with his shirt carefully buttoned at the sleeve in imitation of his other sporting hero, Geoffrey Boycott.

To the intense pride of his parents, Michael went up to Oxford to read Law, which he disliked, and then to York where he studied Anglo-Saxon poetry, followed by an MA at Leeds. His student years were intermingled with many happy times as a star performer in the Jewish social scene in Leeds, where he resumed his cricketing career. Playing for the aptly-named Jesters, he never hit a boundary but was always able to ensure that the match continued until after tea. The Jesters competed in the Barkston Ash League and were famous for their consistent performance at the bottom of the lowest of the leagues, suffering notable defeats by the Inland Revenue ‘B’ Team and the equally dangerous Post Office ‘C’ team.

Well-educated, personable and with a striking resemblance to Bob Dylan, Michael finally embarked on an unconventional path to finding his vocation. While his childhood friends applied themselves to the traditional professions, Michael supervised a a Coca-Cola bottling plant, managed a roller-skating rink, put up tents for holidaymakers in the South of France, and sold encyclopaedias in Australia, with many a picaresque adventure along the way. There was also a short spell at Hambros, where he found the work boring but greatly enjoyed long City lunches.

Walking down Sackville Street one day in 1984, Michael’s eye was caught by the enticing window display of Sotheran’s. Although there was no situation vacant, Robert Kirkman immediately recognised Michael’s potential and took him on to develop an autograph letter department. Within a short time Michael had not only made a success of it, but also met his life-partner, Dorothy Lothian, who was running the print department.

In 1989 Michael left Sotheran’s to start his own business in literary and historical manuscripts, supported by his childhood friend Ian Montrose. Michael rapidly became a respected and hugely popular figure on the international stage with regular appearances at book fairs in Paris, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. He relished book fairs as social occasions as much as business opportunities, and was always ready to leave his stand for a cup of tea and a chat. As he would say, ‘we didn’t have wine in Leeds’. Michael adored his trips to the States where he felt very much at home and had many friends and family. He found New York particularly stimulating, and sometimes wondered if he could have moved his business there. He was a member of the Grolier Club and, in recent years, had formed an important friendship with Declan Kiely, head of literary and historical manuscripts at the Morgan Library.

In 1992 Michael joined the ABA and became a member of the General Committee in 1998. It was the start of his long association with and distinguished contribution to the work of the Committee where his gift for turning a heated debate into a shared experience of laughter was much appreciated. Within a year he became editor of the Newsletter, and of the Handbook, introducing the current format and producing seven editions of a publication which is widely regarded as a model of design and a pleasure to consult. He served as a member of the Export of Books and Manuscripts Committee from 1999, and Chairman of the Trustees of the ABA Educational Trust from its inception in 2010 until his death.

Although Michael made a success of running his own business, he was not temperamentally suited to the isolation of working from home. It might come as a surprise to those who only knew him from the sober prose of his catalogues that he was highly gregarious and a born entertainer. Almost every weekend he hosted a ‘gala night’ for his close friends at his home in Blackheath, when he would slip into his stage persona of Johnny Paris and sing (very badly) a medley of first lines – he could never remember the second line of any song. Stylistically Johnny Paris was somewhere between Frank Sinatra and the Black and White Minstrels.

Michael would have made a wonderful stand-up comedian, or possibly more of a sit-down one. He was not so much lazy as a martyr to chronic lethargy. He could quickly descend into a state of near-bedridden boredom from which, however, he would just as easily recover at the prospect of some slightly eccentric escapade. Few activities gave him more pleasure than ‘styling’ in town, when he would saunter along Jermyn Street admiring the window displays of quilted smoking jackets and brocade dressing gowns and other essential items of clothing which, to his frustration, he could never find in TK Maxx. Michael would love to have been a gentleman of leisure with sufficient private income to indulge his dilettanti interests and expensive tastes. Not long ago he bought a pair of exquisite lemon-yellow chamois-leather gloves, of the kind that Horace Walpole might have owned. He was not at all pleased to discover a few days later that Halfords sold an almost identical pair at a fraction of the cost for shampooing the car.

Born in the wrong age, Michael identified closely with the eponymous hero of Ivan Goncharov’s tragicomic masterpiece Oblomov, which was one of his favourite nineteenth-century novels. The description of Oblomov’s daily struggle to get out of bed is worth quoting* as it could equally have been written of Michael:

As soon as he woke he made up his mind to get up, wash, and, after he had had breakfast, think things over thoroughly, come to some sort of decision, put it down on paper, and, generally, make a good job of it. He lay for half an hour, tormented by this decision; but afterwards it occurred to him that he would have plenty of time to do it after breakfast, which he could have in bed as usual, particularly as there was nothing to prevent him from thinking while lying down.

‘That was what he did. After breakfast he sat up and nearly got out of bed; glancing at his slippers, he even lowered one foot from the bed, but immediately put it back again. It struck half-past nine. Oblomov gave a start.

‘What am I doing?’ he said aloud in a vexed voice. ‘This is awful! I must set to work!

When the decision had finally been made, Michael would apply himself to his work with great mental stamina and, like Oblomov, make a good job of it. He took an equally determined approach to his leisure pursuits which included classical Chinese, Albanian and chess. He collected celadon ware and had become quite knowledgeable about Chinese ceramics, attending handling sessions at the British Museum – no doubt stressful occasions for the curators as Michael was notoriously clumsy, frequently smashing more than one utensil at a time in Dorothy’s kitchen. His interest in Albanian was inspired by Lord Byron’s travels, and by his admiration for the work of Ismail Kadare, the Albanian novelist and first international Booker Prize winner. Kadare was born in Gjirokastra, the UNESCO World Heritage site in Southern Albania, where Michael was seriously thinking of buying property. In preparation for this somewhat fanciful move to Gjirokastra, Michael attended an Albanian evening class at Morley College. After a term of hard work and much homework, he had strung together enough vocabulary to compose a violent short story on the theme of Balkan blood feuds. Hoping perhaps to have left all this behind her, the Kosovo-born tutor gave Michael a respectable mark before disappearing on mysterious sick leave. And so ended Michael’s Albanian experiment, and with it the dream of spending his retirement, smoking a delicious Turkish cigarette within the ancient walls of a beautiful Ottoman town, dressed in Byron’s famous Albanian costume or as close an approximation to it as could be achieved from TK Maxx Tirana.

In reality Silverman belonged to Leeds. It was his spiritual home to which he made regular visits. Many of his closest friends live there, and he had recently taken enormous pleasure in becoming a surrogate father to Lucy, the teenage daughter of his life-long friend, Alan Brown, who died in 2007. Michael was fortunate to have his sister, Louise, living closer to home in London, and he was a devoted uncle to her son, Charles.

Michael Silverman is survived by Dorothy Lothian who enabled him with quiet devotion over many years to keep his unique show on the road. He died rich in friendships and leaves a legacy of wonderful memories.

A memorial event in honor of Michael Silverman will be held on September 12, 2011 at 5 pm at The Grolier Club (47 East 60th Street, New York).

The quotation is taken from: Ivan Goncharov, Oblomov, translated by David Magarshack, Penguin, London, 1954, p.16. The obituary was published in the ABA Newsletter 363. It is presented here by permission of Sheila Markham.