News & Updates

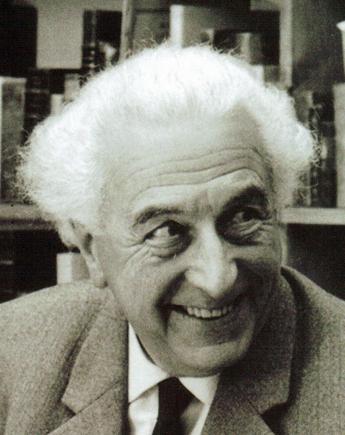

Menno Hertzberger

Vividly I do remember the origin of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, in 1947, although certain details become somewhat vague. From 1939-1945 war reigned in Europe. Five long years had put up extra barriers between several nations. There was no communication. This fact enforced extra chauvinism and worse, hatred. Was there a possibility to do something about interhuman relationship, to bring nations more together? This was my dream; but how could this be realised. Only on common ground, on mutual interests, and therefore, for an antiquarian bookseller, by his love, the Book. To give my idea a possible form I wrote in 1947 a letter to several national associations explaining what I had in mind, viz. to form a truly international organisation which might bring some better understanding between those exercising the same profession.

Immediately I received sympathetic letters from France and the Scandinavian countries. Great Britain was more difficult to join the idea, as they considered their Association as international. A visit to 39 Great Russell Street, then the seat of the A.B.A., gave me the success I hoped for.

I must admit that some of my fellow members of the Dutch Antiquarian Association did not see my aim at all, or at least they were indifferent. But in September 1947 our association could welcome colleagues from Denmark, France, Great Britain, Norway, and Sweden. At Amsterdam there were, obviously, different opinions voiced but after discussing problems and general lines to follow a mutual agreement was achieved.

The following year, in 1948, a second congress was held in Copenhagen. Present were, besides the countries which had accepted already the foundation of the I.L.A.B. in Amsterdam, Belgium, Finland, Switzerland. There, in the Hotel d'Angleterre we discussed, sometimes rather heatedly, in detail the object, rules, etc., thus putting the international association on a legal footing. It was decided that French and English would be the official languages.

In French the I.L.A.B. was to be baptised L(igue) I(nternational) L(ibraires) A(ntiquaires).

As its first president, after voting four times, as one of the “founding fathers” refused again and again to act as president, William Kundig from Geneva was elected. The members of this first committee were: André Poursin, Fernand de Nobele, Einar Grønholt-Pedersen, Percy Muir and myself.

Two months later, at Geneva, practical objects were at stake. One of the results was to produce a directory, followed a few years later, in 1956, by the publication of a dictionary in eight languages for the use of the Antiquarian Bock Trade. Minor, yet from a democratic point of view, major issues were discussed and at following committee meetings, such matters as financial aspects, division of votes for the countries affiliated, and other matters. The Committee met about three to four times each year.

It must be said that there were many obstacles to be overcome, some of them which threatened the further existence of the Ligue. But all these differences were finally conquered. It was contrary to “Semel emissum volat irrevocabile verbum” (Horace). Time progressing the “political” understanding between members of the committee remained more or less harmonious. This ensued automatically as the “fights” were always in view of the common ideal and how to establish this as firmly as possible. We were conscious that a small error at the beginning might become a great in the end, and we all felt our responsibilities. There were a couple of unpleasant affairs, as at the Congress, in 1950, at Paris. However, the discussions did not prevent the sphere of good will.

Now looking back after thirty years one may say that the League responds to its goal. Sixteen national associations are affiliated, including Japan, of which one member is at the Committee.

Business has certainly improved through this interconnection, but more important friendship between many members of different countries has been made, thus tearing down the walls between nations and consequently furthering human understanding. Whether the whole trend of our nice profession has altered for the better is another question.

If I may voice a personal note, it is unsatisfactory that in all countries, with the exception of Germany, anybody can call himself an antiquarian bookseller, and establish himself as such.

Certain repeated efforts from one of the members of the committee to start an international course for young assistants, which would include general culture as well, failed. In this respect I may say that the worst eye disease is to be short sighted. The German Association has at least a seminar, although not international. The N.V.v.A. (Nederlandsche ' Vereeniging van Antiquaren) had real courses for a couple of years, which were considered superfluous' as the Government did not require any diploma to set up as an antiquarian bookseller. To become a baker, or butcher, diplomas are demanded.

Is our trade, without falling into commonplace statements, only business or should we be aware that we handle material to further learning, which is culture?

Hertzberger’s article was published in Aus dem Antiquariat 9, 1977, and is presented here with thanks to the editor.