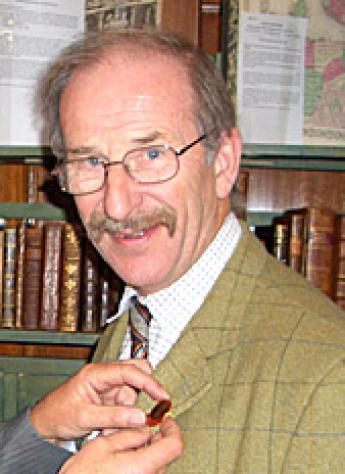

H. M. Fletcher

Keith Fletcher

I am a bookseller – a third generation bookseller and brought up on all kinds of old-fashioned ideas of Town and Gown, Gentlemen and Players, Society and Trade. Many years ago when we visited America regularly my father was invited to join that august New York Club, the Grolier. He declined on the grounds that it was not the right place for a tradesman. Consequently I feel that it is my duty tonight to present to you my credentials as a collector.

I see that I am billed to talk about my Motoring Collection. Well, I am sure that I have no need to explain to an audience such as you that a collecting instinct which runs deep can also spread wide. Be warned, I intend to deviate (I also hope to provide at least a little diversion!)

Before that though, it is necessary to begin; and I intend to begin with several “beginnings”. I am sure all of you at sometime or other have had to field questions about ‘how’, and ‘why’ you started collecting. Here are a few of my answers.

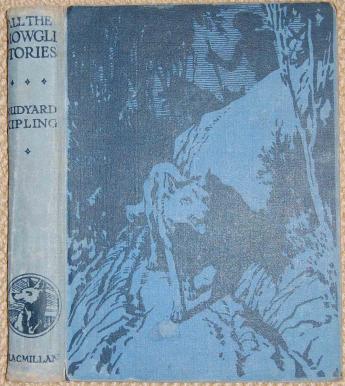

Whether this was my first book I do not know, but it is certainly the earliest to have survived. It is called All the Mowgli Stories in other words Kipling’s Jungle Book in a large-print children’s edition. I was brought up on these stories - my father used to read them to me in bed every night; but there was always a problem, he would insist on starting a new story each night even though we hadn’t finished the previous one. It was my mother who finally solved it. She came in one evening and said “What are you doing, still reading, can’t you see he’s fast asleep?” -“Yes I know” said my father “ but I wanted to finish the story.”

One of my principles in gathering books is to read a book perhaps in a paperback edition and having ‘assessed’ it, either put it back into stock, keep it on my shelves, find a hardback edition to replace it, or, ultimate accolade, find a first or fine edition. [André Gide summed it up when he said “Book collectors do not buy books to read - they buy books because they have read them]. Some twenty-five years ago in the Carnegie Bookshop in New York Dave Kirschenbaum showed us the finest pair of “Jungle Books” any of us had ever seen. Having bought them I said to my father - “You know where those are going don’t you? Home beside All The Mowgli Stories.” - And here is an interesting thing that serves to counter those who ask “Why spend money on a first edition when it is available in paperback?” When I sat down to read, in the original 19th century edition, the stories I knew almost by heart, they were suddenly given a fresh flavour - the flavour of 19th century India and the British Raj, simply through reading them in the original edition.

My father’s first book - I include him here because, as you will see later, we did much of our collecting in tandem - he would egg me on - I would egg him on [and that, I appreciate, is a luxury most collectors do not experience].

My father’s first book - at least the earliest book he is recorded as having brought home from the shop to keep is this one; Purcell’s Orpheus Britannicus 1706 in a beautiful contemporary red morocco. He brought it home because it was such a beautiful copy and in an excess of enthusiasm he had paid too much for it: He would never be able to get a profit. It is noted inside that he bought it on 24. May 1956 and paid £35. Of course eventually we could have got a profit but by that time we couldn’t part with an old friend - indeed we had started putting other fine bindings on the shelf beside it.

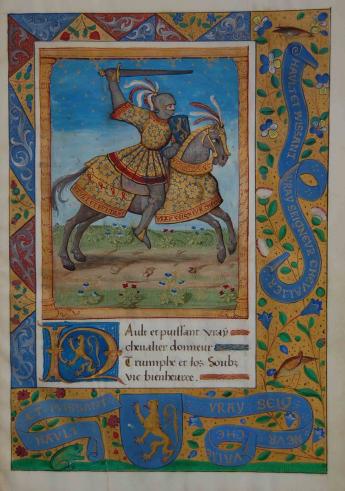

My father collected books about Bayard “Chevalier sans peur et sans reproche” and here is the book which started it. Le Vergier d’Honneur by St. Gelais, Paris n.d. but attributed to Jean Petit, c. 1496. It is a celebration of the military exploits of Charles 8th of France. But this copy is special - it has 4 leaves of vellum with a dedicatory poem beginning with this magnificent miniature of Bayard. It came to us in the following manner. In the late 1950’s The Motcomb Galleries, a storage warehouse in Belgravia, called us in to buy some books. These were, as usual, packed into tea-chests lined with newspaper, and as we emptied each chest we would give it a push across the polished concrete floor into the corner. One tea-chest that wasn’t pushed quite hard enough, stopped in the middle of the floor, and then went clunk! I walked across to see what it could have hit but there was nothing. I scratched my head, picked out all the loose newspapers that had been stuffed back into the chest, and there it was... by far the most exciting book in the whole lot - indeed the only book of any consequence in the lot. Naturally we (that is to say my father, with me doing the encouragement) began to collect everything we could find about Bayard. Here are first editions of the two main biographies of him; by Symphorien Champier 1525 and The Loyal Serviteur 1527. These two texts spawned innumerable editions, many of which we had collected before serious (but not certain) doubt was caste on the identity of our “Knight in Shining Armour” [Perhaps he is Louis de le Tremouille] I was going to say “You can’t win them all” but I don’t think a false start really invalidates our Bayard Collection (and it is still a pretty magnificent false start anyway!)

The beginning of our Rex Whistler Collection is also pretty magnificent. Indeed I was quite proud of the whole collection when I looked through the list of items that The Brighton Museum borrowed for their recent Rex Whistler Exhibition. Some of you may have seen it - I thought it was a fascinating display. In March 1970 my father and I were in New York and bought from Mike Papantonio at Seven Gables Bookshop Copy No. 2 (of 10 on vellum) of the Cresset Press Gulliver’s Travels illustrated by Rex Whistler. Later the same year we missed a second copy [No. 6] sold at Hodgson’s (at that time still in Chancery Lane!) but bought it a few days later from Sotherans. This copy belonged to Dennis Cohen, founder of the Cresset Press, and unlike the 7 Gables copy where the extra suite of plates were coloured and signed on the mounts by Rex, this copy had them left uncoloured. From that day to this I have been trying to locate another copy in an attempt to establish which state might be the norm. I thought I had succeeded a few years ago when I discovered that Paul Getty had a copy - but when I went to look at it I found his copy lacked the extra suite... So... if anyone out there can help.....!

Now I really think it is time I got around to The Motoring Collection. With this collection, I should point out, I was in the driving seat and my father the indulgent passenger. I stress the word indulgent for he was indeed; although on one occasion he did make a more significant contribution. He always said that he was a bookseller “by the seat of his pants - that he had a nose for a book and a little angel sitting on his shoulder.” Anyway he was exhibiting at a bookfair in California sometime in the late sixties where he was confronted with the booth of Graham Hardy, a bookseller from Carson City, Nevada. It was filled exclusively with early automobile catalogues. He had no idea which to select - so he took the lot!! As usual his guardian angel didn’t let him down.

While I was still at school in the 1950’s I used to dream about the £100 MG that I would buy when I was old enough to drive. Studying the For Sale adverts in the monthly magazine Motorsport I quickly realized that if I set my sights pre-war I could get a lot more car for my £100. But I needed to know which were the desirable makes and models; I wanted to read contemporary accounts of these cars. I began looking for books and the first that I came across, on the shelves at 27 Cecil Court, was Road Racing 1936 by Prince Chula of Siam. It was indeed a racy narrative and I devoured it almost at a sitting; and then, because it was a nicely produced book, printed for private circulation, I put it on my shelves and began adding to it. At first they were books about the cars of my dreams, but inevitably the rot set in [You know what I mean - How nice to have such an obviously sympathetic audience!] and I began collecting the books as documentation of the History of Motoring.

I should at this point take the opportunity to correct one false impression that I am sure is already forming in your minds. “Ah well!” you are saying “Its alright for him - he’s a dealer and even as a collector he will always win out over the amateur”. Well, I must admit being a collector and in the trade does leave me well-placed but it does also have its hazards. Very early on, before my ideas on documenting the History of Motoring had fully crystallized, I found, downstairs in our basement vols 1 to 9 of Motorsport marked in my grandfather’s hand 9 vols. 9 guineas. I thought they might possibly be interesting and that eventually I might take them home, but nine volumes was too heavy that night. Two days later a man came into the shop and said “Anything on early motoring?” - “Yes sir” I said, young and eager to please, “We have vols 1 to 9 of Motorsport”. He took one look at the price and couldn’t write his cheque fast enough. Fifty years later and I still haven’t got a complete set of Motorsport!

When I started -“Motoring” was an unusual subject for book collecting. There were plenty of people interested in Veteran and Vintage cars, but few of them ready to recognize the importance of, for example, Knight’s Notes on Motor Carriages, 1896, as one of the incunabula of the subject. The attitude was - “Well it doesn’t say much about the model I have”. The two exceptions to this were my fellow collectors, Jim Barron, whose collection of Automobile Art was magnificent [We did many deals together - the most momentous being my collection of French automobile posters exchanged for his collection of steam-carriage prints], and the late Peter Richley who knew more about both the books and the cars themselves than anyone I’ve ever met.

Of course I haven’t read all my books, who has? But as my collection grew I soon discovered that the general histories usually began with a chapter or two on the ancestors of the car - those monsters moved by crank and lever, cog and pedal, wind and steam and all striving to make the horse obsolete. These were machines of which even I could understand the mechanical workings and they began to intrigue me. Mrs. Beeton is supposed to have said “First catch your hare...” - I would say “First make sure you can identify a hare when you see it” and with that in mind I began to make a list of books I was looking for . The real breakthrough came when I discovered a series of articles by Rhys Jenkins, a member of the Newcomen Society, in issues of The Antiquary for 1896. Early Mechanical Carriages the series was called and although his references were not comprehensive, by the bibliographical standards of the day they were marvellous, leading me to all kinds of treasures. I don’t propose to bore you with a verbal catalogue of my collection but I would like to show you a few items, some of them showing the curious byways up which it has led me: To explain why a 16th century map of China and a first edition of Tristram Shandy should be included in a Motoring Collection.

Of what might be termed the ‘Incunabula of the Petrol Driven Motor Carriage’ the first three books were all published in 1896 (the same year as the repeal of the Red Flag Act and the first “Brighton Run” celebrating the fact). They were Farman. On Autocars : Sennett. Carriages Without Horses Shall Go (Mother Shipton in case you are wondering) : and Notes on Motor Carriages by John Henry Knight of Farnham (The first man in England to be prosecuted for speeding). No-one has ever established a priority among these three, but a few years ago I added to my collection a copy of Salomons. The Horseless Carriage. 1895 which settled the debate.

John Henry Knight also published Light Motor Cars and Voiturettes, 1902, of which I have here two seemingly identical copies. I am sure many of you have been tempted to buy another copy of a book that you know you already have. I offer the following anecdote as a good excuse by which to rationalize your extravagance. When I put the second copy on the shelf beside the first it seemed thicker. I checked title page, imprint etc. Finally the List of Contents revealed 2 chapters deleted and 3 chapters and a frontispiece added, and the adverts at the end had been reordered. Had they not be put together I would never have discovered two issues.

The Automobile Handbook 1904 is something of a milestone in that it is the first edition of the RAC Handbook and gives some delightful insights into the ‘mores’ of the early motorists. The following extract appears under the heading Armorial Bearings. - “Automobilists who desire to use armorial bearings on their cars have to pay a duty of £2. 2s.”

The Motor Show Catalogue 1903 comes from the first show sponsored by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders. This show is still held annually to this day. For most of its life it was at Earls Court but now at the Birmingham NEC. I have the first 29 years, uniformly bound in half green morocco. They came out of the loft of a small semidetached house in North London during a house clearance. I have no idea how they got there or who had them bound so extravagantly.

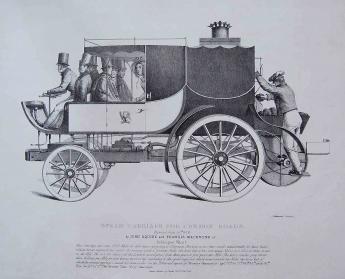

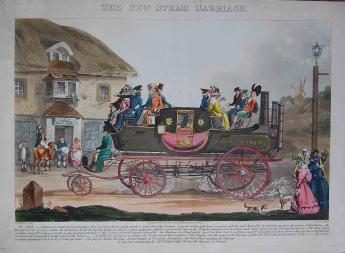

Proceeding in chronological reverse gear we arrive at the 19th century and the heyday of the steam carriage or perhaps more accurately the steam coach. Steam-driven versions of the stage coach for a time in the 1820’s and 30’s ran regular bus services in London as well as some well-publicised excursions further afield - Goldsworthy Gurney to Bath; Col. Maceroni to Watford; and the incredible Ogle and Summers trip from Southampton to Liverpool in 1832 for which I have a typed copy of a 14 thousand word manuscript account. The two most prominent builders of this time were Sir Goldsworthy Gurney and Walter Hancock. Hancock was a fine and inventive engineer whose series of vehicles ran a regular service for many months from Stratford to the City, all recorded in his Narrative of Twelve Years Experiments... 1830. Gurney was a well connected entrepreneur and obviously much better at publicity for although his carriages were no match for Hancock’s there are many more contemporary prints of his machines than any other. The New Steam Carriage is probably the finest of them and this aquatint spawned many copies.

Rudolph Ackermann, whom you all know as the leading publisher of colour-plate books of the nineteenth century, actually arrived from Germany in 1787, aged 23 as a trained carriage designer. In 1817 an old school friend, now coachbuilder to the king of Bavaria, sent him designs for a new steering system to stop coaches overrunning their wheels. If any of you, as I did [and had the inevitable accident], built a ‘soapbox cart’ with your old pram wheels, that is how coach steering originally worked. The new system put the wheels on stub axles and linked them with a bar so that they turned in parallel. Ackermann was requested to take out an English patent for it, but, as he explains in his preface to Observations on Ackermann’s Patent Axle 1819, unless the inventor appeared at the Patent Office in person then his agent was obliged to register the patent in his own name. Ironically it is still known as Ackermann’s Axle - poor old Georg Lankensperger is totally forgotten - and Ackermann’s Steering System is still used on the car you drive today.

So much for colour-plates - but some of you, I know, are more interested in typography. Here is a contemporary oil painting of Dr. William Church’s London to Birmingham Steam Coach although it is very doubtful if it ever moved satisfactorily more than a few hundred yards. Church was an American born in Vermont in 1779. He came to England in 1820; spent nearly forty years in Birmingham and returned to Vermont in 1859 where he died in 1863. His interest to me is obvious from this painting - but his wider interest to some of you is that, in 1822, he invented and patented the world’s first typesetting machine. The very idea so frightened the typesetters that reports of it were regularly regarded as a hoax. Huss: Dr. Church’s Hoax gives the whole story. I bought this painting from Mr. Gates at Ackermann’s while they were still in Bond Street, and he told me he bought it in America - which makes a nice circular story.

Earlier I mentioned Col. Maceroni’s trip to Watford; more precisely from Edgware to Bushey. Here is a copy of the large paper edition of Turner’s Annual Tour. This series is, I am sure, familiar to all of you who browse in old bookshops.

It is a ‘keepsake-type’ publication regarded mainly as a vehicle for Turner’s engravings. I am sure that most people who handle it do so only to extract the engravings. I was therefore quite excited to find, in the 1834 issue Leitch Ritchie’s Wanderings by the Seine, a 5-page eyewitness account of Maceroni’s trip to Bushey. In the words of Michael Caine “Not a lot of people know that”.

In May 1966 I was in Salcombe learning to sail my newly built dinghy and missed a sale (the other kind!) at Sotheby’s. To my dismay in it had been a copy of this book Pocock : The Aeropleustic Art 1827. But all was not lost - or so I thought - for it had been bought by Charles Harris Junior of Francis Edwards who could usually be relied upon to turn over their auction purchases on the SPQR principle [Small Profit Quick Return - a favourite of my father’s] However when I approached Charles he confessed that he had bought it for his own aeronautical collection. It was another 26 years before the next copy came up in Phillips and I had to pay ten times the price.

Pocock invented dirigible kites, with two lines, long before the modern stunt kite was ever thought of, and put them to various uses including the pulling of carriages -the ancestor of the modern kite-buggy that my son and his friend race across the beach on thinking it is the latest invention.

Sand yachts have an even longer history. Simon Stevin, military engineer to Prince Mauritz of Nassau, and, incidentally, the inventor of the decimal system, built this one for the Prince in 1600. The engraving shows the proud owner doing 20 miles an hour on the beach at Schreveningen. He had just beaten the Spanish invaders at the Battle of Nieuport and the captured Admiral Don Mendoza is among the passengers he is seeking to impress. So too is the 17-year old Hugo Grotius whose Collected Poems 1617 contain a number in praise of the Windtwagen , the “Currus Veliferus”. My copy is from the Duke of Devonshire’s library and has the author’s presentation inscription on the title-page. My purchase of this magnificent engraving, [215 x 53 cm] in 1967 began a chase which took me along some startlingly devious paths to some very diverse [and diverting] prizes.

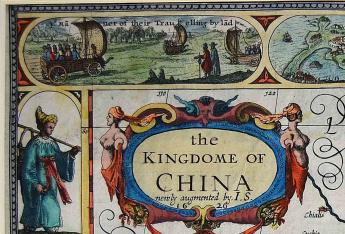

Early writers on China, Marco Polo for one - Giovanni Botero for another, mention that the Chinese used sailing carriages. In the light of this, 16th Century Dutch cartographers, looking for things to fill a country for which they had so little geographical detail, took to using little wagons looking like wild west prairie schooners but with a sail. After Stevin came along in 1600 they started using his Windtwagen as a model and then a few generations later scholars pointed to these maps and accused Stevin of plagiarism.

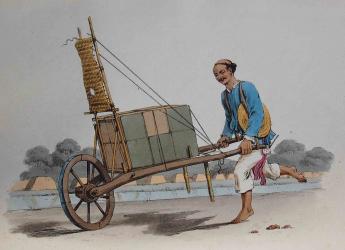

It is not until William Alexander, official artist to Lord McCartney’s Embassy to China, publishes his illustration of a sailing wheelbarrow in 1799 that Stevin is finally exonerated. Nicholas Fabri de Peiresc, a judge at the parliament of Aix, was one of the all-time great patrons of learning. He was an early disciple of Galileo; the first man to verify Harvey’s Theory of Circulation by experiment; his work on optics was used by Newton; and Grotius claimed that without his help and encouragement De Jure Belli would never have been written. His qualifications as a scientific observer can hardly be doubted, but in his description of his ride in the Windwagen (for which he made a special journey to Scheveningen) he waxes so lyrical about its speed which, I quote “... makes men which ran before seem to run backwards” that he communicates even to us of the 21st century who take speed for granted, the excitement of Stevin’s invention. Gassendi’s Life of Peiresc was first published in Paris in 1641. Here is the first English translation - by William Rand 1657. Rand dedicated it to John Evelyn whom he called “The English Peireskius”. My copy is from The Evelyn Sale with the “JE” label, but I don’t think that it can be claimed to be the Dedication Copy. I wonder what happened to that?

In Vol 2, Chapter 14, of Tristram Shandy, Uncle Toby and Dr. Slop discuss Peireskius’s feat of walking from Paris to Scheveningen to see the Windwagen. My first edition is fine in contemporary calf. I also have the first French translation.

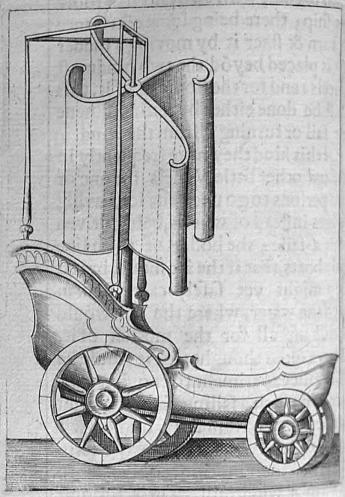

Lastly we have two learned clerics from opposite ends of the earth. Bishop John Wilkins was one of the Founders of the Royal Society and his book Mathematical Magic 1648 went through four editions by 1700 . It is the first English text-book on Mechanics and gives much information on Stevin’s Windtwagen, including the reference which led me to Gassendi and Peiresc. But not content with reporting the ideas of others he adds ingenious suggestion of his own; a vertical windmill geared to the wheels of a carriage: Like those signs one sees outside shops, it works whichever way the wind is blowing. (Fig.12.) For the other cleric we must again go to China where, in the mid-seventeenth century, a Belgian Jesuit called Father Ferdinand Verbiest was introducing the Emperor Cam -Hi to Western Science. In his book Astronomia Europaea 1687 he describes how, to entertain the Emperor, he built a carriage about two foot long, in the middle of which he put a vessel of live coals surmounted by an aeolipyle (A simple form of steam turbine first described by Hero of Alexandria in 1575) which drove the model round the palace yard. Although, admittedly, only a model, and not a mechanism which would have worked at full scale, this is the earliest account I have found of a mechanically-powered vehicle. I have dubbed him “The Father of the Automobile”.

Fillipo Morghen Viaggia Alla Luna 1768. This last piece of “Automobiliana” is pure fantasy. I fell in love with it the moment I saw it, but it was only after I had bought it that I realized that I had a perfectly legitimate excuse for adding it to my collection. It is illustrations of Giovanni Wilkins’ Voyage to the Moon (Yes! he of the Royal Society) and plate 3 is a sailing carriage - the original moon-buggy.

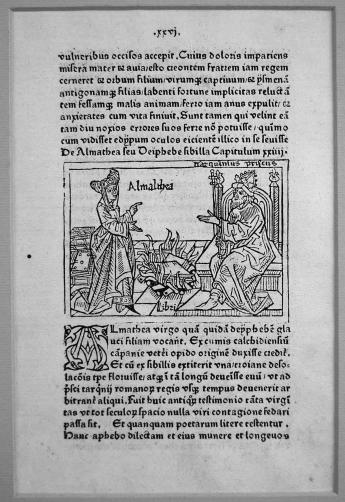

I have various pieces of “Printing Ephemera” framed on my walls that I inherited from my father - a Gutenberg Bible leaf ; a leaf from Higden’s Polychronicon printed by Caxton 1482 which carries the account of the Battle of Hastings ; and this leaf from Boccaccio’s De claris mulieribus. Ulm 1472 with, on the back, a label by my father headed “The First Lady Bookseller”. The lady is Almalthaea, one of the Sibylline oracles. She offers the nine Books of Wisdom to King Tarquin of Rome for a price which he finds too high. She throws 3 books on the fire and offers the remaining 6 for the same price. The King is indignant and refuses. She throws 3 more on the fire and offers the last 3 for the same price. The king finally has the good sense to buy them. Verb. sap!

The article is published on ILAB.org by permission of Keith Fletcher. Thank you very much.