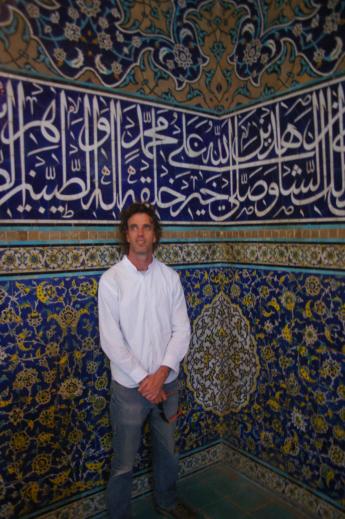

Hugh Myers in Iran

By Hugh Myers

Does anyone know of any antiquarian booksellers in Iran? Follow Hugh Myers, cataloguer and researcher at Hordern House (Sydney, Australia), on his amazing trip through the country.

I visited Iran for thirty days in May of this year, and have compiled a few notes on the rare book trade in this country – or more precisely the lack of it. Prior to departure I contacted a good number of well–informed dealers in the United Kingdom, Europe and North America for any leads, and nobody knew of any antiquarian booksellers operating in Iran. This seemed curious, and was largely confirmed by my experience on the ground. Nonetheless I did encounter some interesting rare books and manuscripts in museums and collections, including Armenian incunabula and medieval manuscripts.

My itinerary was typical of central Iran and the Caspian Sea hinterland: arriving in Shiraz, then Yazd, Esfahan, Kashan, Hamadan, Qazvin, Alamut and departing from Tehran. Travel is easy and comfortable, the people are consistently gracious and hospitable, and it was a pleasure start to finish. Although my Farsi is limited to simple greetings and essentials, it was still possible to communicate as some people have basic English and a few speak it well.

Throughout my time in Iran I asked a wide range of people about antiquarian booksellers and was unable to locate anybody who sold rare books and manuscripts exclusively. No doubt there is good material in private hands, but at this stage a distinct trade has not emerged from the general market in antiques and antiquities. I saw a few shabby manuscripts in shops selling old wares in the bazaar at Shiraz, and a small cluster of antique dealers on the periphery of Imam Square in Esfahan had some marginally better material. However, nothing was really old, the most impressive item being a nineteenth century Qajar Quran with a little gilding for US$500 (negotiable of course, as with everything here…)

In Kashan I had better luck, accompanied by a local businesswoman who was familiar with the antique dealers in the local bazaar. Nonetheless, only one man held good material, which included an eighteenth century astronomy text amongst a small number of interesting books. Most prominent was an early fifteenth century manuscript of Hafez with a dozen competent miniature leaves, executed in a Persian court in northern India and bound in nineteenth-century lacquered boards. The dealer wanted US$15,000, and insisted that a manuscript of similar age and quality written in Iran would be priced threefold. So no bargains here, but nonetheless it goes to show that with a local contact there are books to be found.

The lack of a rare book trade is most probably due to the simple fact that letterpress printing is relatively late in Iran, and that until modern times the population remained small and educational opportunities were limited. The historical conditions that facilitated large-scale production of books in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was not paralleled in Iran, and the manuscript tradition remained strong in religious instruction and pedagogy. There simply are not a lot of old books in circulation, and the manuscripts that have survived are treated as cultural treasures. Iranians are cautious of European expropriation of their cultural heritage following the arbitrary removal of ancient artefacts by European travellers during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and this reluctance to see historical material leaving the country obviously extends to books and manuscripts too.

It is possible that a market may develop for modern literature printed in Iran that was censored and destroyed en-masse during the early years of the revolution, but it is hard to assess this is an environment where the state continues to play a role in determining what is permissible reading and publishing. Certainly there are second-hand booksellers with modest shopfronts, street stalls and even wheelbarrows peddling their wares, a direct reflection of a literate and intellectual culture.

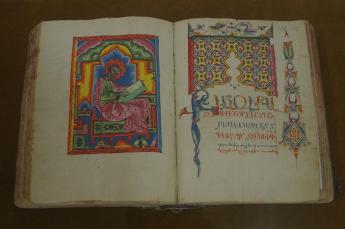

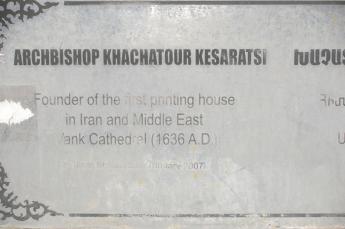

Any bibliophile in Iran must visit the Armenian enclave in Esfahan, long known as New Julfa and settled in the early seventeenth century onwards. In this sheltered Christian community the first letterpress printing in Iran took place - under the supervision of the prelate Khatchatur of Caesarea a handful of Armenian theological works were printed between 1638-1650. The prelate is today honoured with a monumental bronze where he is depicted proudly holding aloft a piece of type. The Valk Cathedral is the centrepiece of the enclave, and is annexed by a museum containing a few examples of the Armenian incunabula (now fabulous rarities) alongside a range of books printed in Amsterdam for this community from the seventeenth century onwards. An early box of type is exhibited along with printing equipment, but the highlight of this collection are the illuminated medieval manuscripts from Armenia proper, many of which are in their original bindings with metal-work covers and leather flaps protecting the edges. It is an opportunity to see the work of master illuminators of this tradition from the fourteenth century onwards, and a style of binding that incorporates European and Arabic elements in a distinctive manner.

Also in Esfahan is a museum of antiquities adjoining the parklands of Chehel Sotoun, the so-called Palace of Forty Columns. Aside from its excellent archaeological material, this collection contains first rate examples of calligraphy, miniatures and illuminated books from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, and showcases paradigm material from the Islamic manuscript tradition. Of special interest here are the bindings with lacquered boards, executed with an astonishing degree of skill and precision (lacquer, like miniatures, originated in China but later became a distinctly Persian craft). There is another good calligraphy museum at the Qajar palace in Qazvin that is well worth visiting, although the most impressive calligraphy I encountered was actually kufic lettering on tenth century ceramics in a temporary display at the mausoleum on Ali ibn Sina (Avicenna) at Hamadan.

In conclusion, I assume that top-end manuscript material leaving private hands is typically handled by the large European auctioneers, who have the market prominence to attract both buyers and sellers across disparate cultures. I am unsure if opportunities exist for the antiquarian book trade, as the language barrier and export restrictions will remain significant obstacles. However, given that a significant portion of the prosperous and educated middle classes left in the aftermath of the Revolution, it may well be that the best market for Iranian books is with expatriates in Europe, North America and the United Kingdom.

But books aside, go and visit Iran anyhow. The history, architecture and antiquities attracted me, but it is the people – so remarkable for their sincerity and gentle manner – that will make me return.

***

Text and pictures courtesy of Hugh Myers.