Collecting - The Clark Nova Express: Horror Fanzines, the Mimeo Revolution and William Burroughs

By Jed Birmingham

One of the perks about working on Reality Studio is the opportunity to get in contact with some very interesting people. Johnny Strike, Gary-Lee Nova, Jim and Roy Pennington. All have amazing stories and fantastic tales to tell. And then there is Graham Rae - a polarizing figure for some as a look back at old forum posts proves. Yet all polarizing figures have one thing in common: energy. Graham has chutzpah in spades. I am firmly in Graham’s camp because I recognize and admire a follow obsessive. He wears his passions on his sleeve and his enthusiasm is contagious. In addition, he consistently brings interesting items to the Big Table, or Reality Studio, as the case may be.

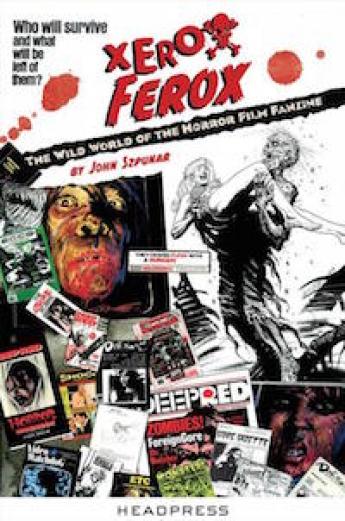

As just one recent example, Graham posted on the forum about Xerox Ferox, a collection of interviews with publishers of and contributors to horror fanzines. This is an intimate, close-knit world full of larger-than-life figures and an ecosystem that Graham was a part of in the late 1980s and early 1990s, while writing for legendary horror zines like Deep Red. As Graham mentioned on the forum, he is interviewed in the book. Well, I finally got around to getting a copy and let me assure you it is full of hellraising tales. The book exceeded my wildest expectations and I highly recommend it (...)

Before reading Xerox Ferox, I was totally unaware of almost all of the zines described therein, such as Gore Gazette, Deep Red, Sleazoid Express, and Trashola. To say nothing of the related world of grindhouses, drive-ins, independent bookstores, distributors, and mail-order businesses that inspired and supported horror zine culture. But unknowingly, I had trespassed into this all-hallowed underground. Merely as a tourist mind you. I just casually dipped my toes into the chilling waters of the Black Lagoon. I was never baptized. I was not as Chas. Balun, a horror zine legend, labelled horror fanatics, a true believer. I was never born again, or, should I say, was never undead.

Yet around the time Bill Landis and Will McDonough documented the exotica of 42nd Street in the early 1980s within the pages of Sleazoid Express, I was doing my own walk on the wild side on a smaller and safer scale. See, my brother and I visited my father in Connecticut several times a year and we would get on the Bieber bus in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, and meet up with him at Port Authority in New York City. In the days before the internet, cell phones and text messaging, it was something of an act of faith that when we got off the bus that my father would be there to greet us and whisk us away from the dangers of the bus station. If my father was late, we had to fend for ourselves, which meant fending off the local wildlife. As we got older, let’s say when I turned thirteen, my brother and I made the transfer at Port Authority ourselves and got on to another bus to take us up to Connecticut or back to Pennsylvania. That meant a layover.

Now, I know nothing of the Deuce as Landis and McDonough as experienced it, but I can assure you that for a young teenager Port Authority in the mid-1980s was a horror show. Scary yet utterly fascinating. Zombies and vampires roamed wild throughout the dark passages of the station. My brother and I would cram together for safety in a bathroom stall and take turns doing our business. And to be sure, business was being conducted in the stall next door. I remember a young hustler with pinpricks for eyes frantically running up to a bored policeman screaming “He’s gonna kill me!” and then scurrying off terrified. Just minutes later, a hulking man shuffled by in pursuit, much like Frankenstein’s monster, mumbling curses to himself. The policeman merely laughed and directed the zombie toward his prey.

Without a doubt, Port Authority made an impression on me. I have never forgotten the handful of hours I spent there. Do not get me wrong, there was no saison en enfer such as Landis describes; but it was a little taste (and smell) of what was cooking in Hell’s Kitchen. Years later in the post-Giuliani Era, I toured the bars around Port Authority with my future wife and brother-in-law. The glory days of the Deuce and its walking dead was fading into twilight but there were still flashes of local color. Siberia, Howard Johnson’s, Rudy’s, Holland Bar. At some point during the hours we spent in the Holland Bar, I realized I wanted to spend the rest of my life with this woman. Amongst all that loneliness and despair a relationship dawned.

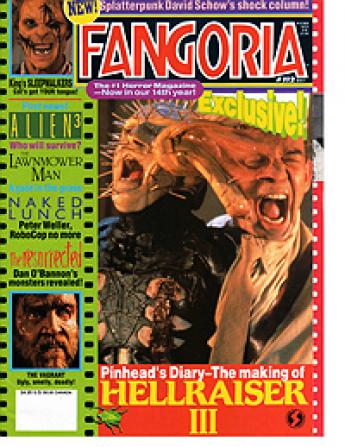

As a teenager back home in suburban Pennsylvania in the safe confines of the shopping mall and my parents’ furnished basement, I again edged the abyss described within the pages of Xerox Ferox. I spent hours browsing within Waldenbooks, looking, but never buying. I was incredibly tight with a dollar and a good portion of my money was pumped into the slots of Rampage and Xenophobe in the arcade on the second floor. But I was a dedicated flâneur of the mall bookstore and I camped out in the photography section hoping to catch a glimpse of some soft-focus softcore in the how-to photography books. In the magazine section, I loitered with the mainstream porno mags, hoping to get my hands on an issue of Penthouse with Vanessa Williams (as well as an underage Traci Lords). I also flipped through the mainstream gore mags, like Fangoria and Cinefantastique, and related periodicals, like Femme Fatale.

From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, I watched scores of horror movies. Alien and John Carpenter’s The Thing were, and still are, favorites, but I also rummaged through the local video stores and got my hands on more ghastly and underground delicacies, like Bad Taste, Peter Jackson’s Meet the Feebles and Dead Alive, Blood Feast, Blood Sucking Freaks, I Spit on Your Grave, Susperia, Demons, Zombie, and Cannibal Holocaust. Surrounded by wood paneling, I scoured the pay channels for anything left of the remote control. I watched all the Emmanuelle films and the occasional Mitchell Brothers film, like Insatiable; I saw quite a few Troma movies; I dug Spaghetti Westerns; I would thrill to B-movies, like Gator Bait, and was always on the lookout for femme fatales, like Playboy Playmate of the Year Claudia Jennings, who died in a car crash in 1979 on Highway One before reaching age 30. Nobody rocked a blue jean vest and daisy dukes like Claudia. God rest her soul. I loved Hollywood Shuffle and I’m Gonna Get You Sucka, which led to Shaft, Blacula and other Blaxploitation flix.

Without a conscious plan of attack or goal in mind, I was rapidly immersing myself and getting an education in exploitation film. But I never really schooled myself on the subject. This was with one exception a largely solitary pursuit. It never occurred to me that there was a community of likeminded individuals out there sharing their discoveries and obsessions. The curiosity that ran wild with William Burroughs, and found room to roam at RealityStudio, had yet to fully develop. I was an intellectual loner, not because I was a rebel or outsider, but because I was too self-conscious to bring any attention to myself or my ideas. I was worried about looking stupid or making a mistake. It took years to realize that the only way you learn anything is by sharing your ideas with others and having those ideas put under scrutiny and challenge. Making mistakes is a crucial part of learning anything. This post is an attempt to learn more about horror zines so I hope all interested and knowledgeable parties hit the comment section hard with additions and corrections.

Anyway, long story short, I never flipped through the back pages of Fangoria and ordered what was on offer there. Reading through Xerox Ferox two decades later, I realize this was clearly my loss. Horror fanzines were not something I grew out of, like many people, but something that I matured into much too late. In my forties, I now document and pursue my obsessions through self-publication in a way I never even considered in my youth. Like Burroughs and Bukowski, I was a late bloomer.

Even if it is in some ways too late to participate in any meaningful fashion in the world of horror fanzines, I am still ready for Xerox Ferox now. This is par for the course with me. I never fully appreciate anything in the heat of the moment. A happening does not happen until it has happened. I never take the opportunity to experience anything directly but choose to immerse myself in an experience after the fact. I feel comfortable as a historian but awkward as a participant or eyewitness. It is only after the passage of time and the application of a patina of history that I can appreciate anything. I hate this about myself but that is the way it is.

As such, Xerox Ferox is one of the most exciting books I have read in some time. As an obsessive compulsive with a touch of paranoia, Xerox Ferox plugs into what everything in my life relates to: William Burroughs and little magazines. Just as little mags provided an outlet for non-academic and, in some cases, outlaw writing, horror fanzines provided an outlet for commentary on outlaw cinema beyond the considerations of accepted taste and, in fact, glorying in bad taste.

Underlying Xerox Ferox is a theme of community and technology. The book wonderfully documents the changes in film technology from 8mm, 16mm and 35mm film to VHS and beta to DVD to mpeg and how these technology shifts altered the nature of the horror fanzine community. Moving from the Video Revolution to the Mimeo Revolution, the various interviews also thoroughly cover how alternative communities were built through changing print and digital technologies: hectograph, mimeograph, offset, xerox, laser printers, desktop publishing. Xerox Ferox is a must-read for anybody seeking to learn more about the printing technologies that got the Mimeo Revolution spinning.

For example, here are the thoughts of Steve Bissette on mimeography from the opening interview:

“Now, I don’t know how many of the terms I’m about to use will make sense to your readers, but most of [the EC comic fanzines] were either done as carbon copies or with mimeographs. That was an early form of printing were you’d actually have to type onto these stencils. And if you wanted to draw on the stencils, you’d have to use cutting tools that were specifically designed for them. I used those in grade school and a little bit in high school. At the time, schools were still using mimeo for papers. I did get to play with trying to do a comic on a mimeo. It was hard. You couldn’t draw the way you’d normally draw; you couldn’t use a pencil or paper. You had to draw on this opaque blue-black surface that was sort of like a messy sheet of carbon paper. You’d have to carve into that to leave an impression on the mimeo master. And that’s what you’d run your copies from. It had this specific smell to it – I can smell it right now, as we’re talking.

That kind of thing, seen today, is beyond archaic. You just can’t picture the process of what mimeography was about. But that’s how most of the early fanzines were done. The cost of printing was expensive. You didn’t have photocopiers; they didn’t exist yet. That kind of technology didn’t emerge until the late sixties. You certainly didn’t have the equivalent of a photocopy shop in every town the way you do today. And typesetting was still done the old way where you actually set the type in these large flatbeds. The type was metal slugs. All of that was beyond the reach of any kid. You’d have to be a really devoted adult fan to do something like that. So the first fanzines that I actually saw printed were in the late to mid-sixties.”

Other interviews provide similar details about offset, xerox, and desktop publishing. Xerox Ferox tells the history of the changing landscape of printing technology and provides case studies of how that technology affected zine production and distribution as well as how it shaped the philosophy of horror zine culture.

The challenges facing horror zine and Mimeo Revolution publishers are in many cases eerily similar. Reading Xerox Ferox the general consensus is “If it is easy to do it is not worth doing.” Or more importantly, not as much fun. The horror zine scene reached its creative apex with limited financial means and technical materials at their disposal. The cut-and-paste aesthetic, a hallmark of the zines, came out of necessity as much as any attempt to make a design statement. Lack of cash and lack of access to high-end printing equipment required zine publishers to do more, and do more interesting things, with less. It was also a challenge in terms of time and effort. If you wanted to make a zine, you really had to want it. Michael Gingold of Scareaphanalia states:

“Well, I always say that the great thing about the internet is that it gives everybody a voice, and the bad thing about the internet is that it gives everybody a voice. Back when we were doing fanzines, you really had to have the enthusiasm to make the effort to type them up and lay them out, copy them and send them. You really had to have a commitment to the genre and an interest in communicating. Nowadays, anyone can go on a message board and throw their comments up.”

Furthermore, horror zines were labors of love, not money. They were never thought of as an investment towards some future pot of gold down the road. The zines were made because the publishers felt compelled to scream into the void and see if there was an echo.

In my opinion this definitely holds true with best mimeo mags as well. One of the primary reasons little mags of the 1960s are superior to the 1970s is because self-publishing was more difficult to do a decade earlier. There was little to no organized support or distribution system. Little mag editors were on their own to find an audience and pay printing and distribution costs. This was before government grants and the development of a literary bureaucracy. Only after the perseverance and eventual success of the mimeo pioneers did such a structured environment develop.

Surely the early days were difficult and frustrating but such barriers required the first responders to be supremely motivated, i.e. obsessed, and the limitations of the medium paradoxically allowed more freedom and ultimately more creativity in production and distribution. It is no surprise that when money, however minimal, seeped into the mimeo ecosystem, the publishers left the mimeograph behind for offset, which was easier and “more professional.” This is also to say that things became more routine (and boring), not just in terms of regular publishing schedules (such as printing monthly or quarterly), but also in terms of content.

Xerox Ferox makes clear that the golden age of zine production was pre-Internet. Eventually the print zine declined with the ease of publishing online. Yet most zinesters agree that blogs lack the energy and attitude of the hardcopy originators. Zines exploded precisely because information was so difficult to come by. The ability to find any factoid on the internet made the creation and distribution of print zines unnecessary. But again ease came at the expense of fun and passion. Dennis Daniel states of zines like Deep Red:

“It’s an era that’s gone, but that’s OK. Things are supposed to go. Things are supposed to evolve and change. And now, everything you’d ever want to know (right up to when Rick Baker’s taking a shit) can be found on the internet. . . . But that’s what makes those magazines so coveted today. That’s what makes them mean so much. And if you live long enough, you have the opportunity to look back and say, “Oh my God . . . it’s not like that anymore. But, boy am I glad to have been a part of it.”

If something is easy to do, lazy people, and thus, lazy minds, will be drawn to it. Pre-internet, to create a filmography or to document the history of a particular underground film took real skill and effort in terms of research. This difficulty meant that only the most persistent, dedicated and obsessed individuals would take the time and effort to attempt it. The result was a better, more spirited, more individualized publication.

Similarly in the world of book collecting, there is much talk about the decline of the hobby in the information age. One primary reason for this is that the internet made book collecting easier to do. The search engines do all the legwork. Currently the driving force in book collecting is not the search or the quest, which can be accomplished in seconds, but economics. Can you afford the book? Unfortunately, the internet has also standardized prices so there is little to no difference in pricing on a particular book. The days of walking onto a bookstore and finding a rare, unusual, undervalued book are over. The internet has democratized knowledge and standardized pricing to the detriment of book collecting as a hobby.

What is the extent of the crossover between little mags and horror zines in general? Xerox Ferox makes clear that punk culture was a major influence on horror zines, but what about the spirit of the Mimeo Revolution? For example, Stephen King early in his career published a poem entitled “Brooklyn August” in the Baseball Issue of Io Magazine, alongside Mimeo Revolution stalwarts such as Jack Spicer, Stan Persky, Paul Blackburn, Robert Duncan, Ed Dorn, and Charles Olson: “below, the old men and off duty taxi drivers/drinking big cups of Schlitz in the 75¢ seats,/this Flatbush as real as velvet Harlem streets.” A skeleton in King’s closet later exposed to the light of day in the odds and sods collection, Nightmares & Dreamscapes. Not surprisingly, horror zine publishers and contributors list Beat writers as major influences on their worldview if not their writing. In what other ways were the literary counterculture and the horror zinesters blood brothers?

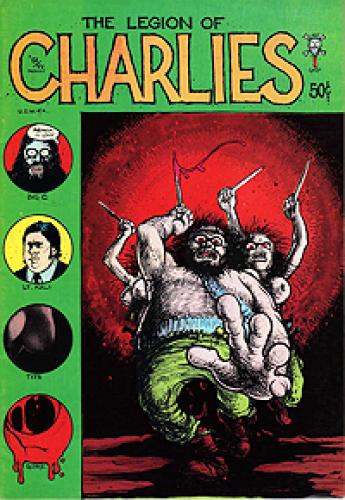

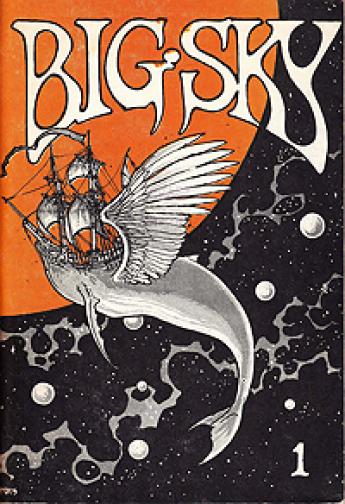

Tom Veitch jumps to mind. Veitch is a poet who got his start with Ted Berrigan’s C Press, which published Veitch’s Literary Daysin 1964. C Press was also involved in issuing C Comics #1 & 2, which featured comic illustrations by Joe Brainard accompanying text supplied by various poets. Brainard took his cue from Pop artists, such as Warhol and Lichtenstein, who appropriated comic strip characters in their artwork. Brainard made a name for himself by co-opting Nancy. Siglio Press celebrated Brainard’s work in this regard in its popular The Nancy Book. Brainard merged comics, pornographic innuendo, and camp creating a more literary form of Tijuana Bible but Tom Veitch, post-C Press, drew on the rich tradition of horror comics. Tom’s brother, Rick, is a well-known and well-regarded illustrator with credits including the legendary Swamp Thing, which he illustrated along with Steve Bissette, the mentor figure of Xerox Ferox. In the early 1970s, Tom and Rick collaborated on an EC Comic parody entitled Two-Fisted Zombies. In addition Tom and comic illustrator Greg Irons collaborated on horror inspired comics such as Deviant Slice #1, The Legion of Charlies, and Skull #6. The Veitch/Irons team also appeared in little mags, notably Bill Berkson’s Big Sky #1, which featured their eco-minded and horror inspired comic The Creature from the Bolinas Lagoon. Irons provided covers for various Big Sky publications including a cover for Big Sky #1 that enters the realm of the fantastic.

As I have written before, Tom Veitch was obsessed with William Burroughs. El Hombre Invisible is a ghostly presence in Veitch’s horror comics, if not an overt one, as proven by The Legion of Charlies. The comic opens with a mock newspaper, The San Francisco Chiclet, which is identical in format to Veitch’s The Naked Express that appeared in Aram Saroyan’s Lines and as a standalone piece of ephemera. I have written about The Naked Express and its link to Burroughs. The San Francisco Chiclet slyly references Hassan I Sabbah and the back pages of Charlies contains an advertisement for a comic rendition of The Nova Formula, a “theory which shows that history will spiral into disaster” that also grapples with the “evolutionary goal [to] travel to the stars.” Veitch relies the Burroughsian routine in developing the Charlies storyline, which involves power hungry President Nixon and Vice President Agnew joining forces and eventually being consumed by zombie Manson family members along with convert Lt. William Calley of My Lai infamy. “The Conversion of President Nixnerk” that ends Charlies is pure routine in form and content. “Roosevelt After Inauguration” comes to mind. A routine that could be spun as a great horror comic by the way. Purple-assed baboons run amok craving the flesh of Supreme Court Justices!!

Does a taste for Burroughs make one predisposed for a fascination with horror? Burroughs was clearly an influence on science fiction and thus sci-fi zines. For example there was a sci-fi zine named Nova Express. This further suggests that after Naked Lunch, Burroughs’ most influential novel is probably Nova Express, at least in terms of influencing other writers. There has always been a horror element to Burroughs, who was no doubt a writer of shock and special effects. The Burroughsian universe is a horrific underworld and Burroughs graphically revels in its blood, guts and seminal fluid.

Xerox Ferox makes clear that there is a close affinity between the avant garde and the exploitation genre. Both are created with limited means by highly motivated individuals pursuing an extremely personal and highly original, often unusual and transgressive, vision. Greg Goodsell states:

“Independent filmmakers don’t have any money; they use their friends as actors, etcetera. It’s like when I was working at small newspapers and large newspapers – if you’re small, you can do what you please. You can bring neuroses, likes and dislikes to a project. You can bring your own quirk and personality to it and no one is in the front office saying “You can’t do that.” So yeah, that’s the appeal about no-budget independent filmmaking.

Q: The art film and the down-and-dirty exploitation film don’t differ much, in that respect.

Goodsell: The bigger a project is, the more people you have with vested interests in it. They say, “You can’t do that, you can’t step on these toes, and you have to use this actor.” It’s just artistic freedom. The art film offers artistic freedom, and the low budget exploitation movie (which is ostensibly made to make money) offers the same sort of freedom.”

Let not forget, what is for me, the most important lines Burroughs ever wrote:

“That’s the sex that passes the censor, squeezes through between the bureaus, because there is always a space between, in popular songs and Grade B movies, giving away the basic American rottenness spurting out like breaking boils, throwing out gobs of that un-D.T. to fall anywhere and grow into some degenerate cancerous life-form, reproducing a hideous random image.”

Not surprisingly, Antony Balch, who directed Burroughs’ cut-up films, was an exploitation director. When you think of it, Towers Open Fire is a sci-fi exploitation flick. Burroughs is likewise an exploitation writer. Junkie is after all pulp fiction as is Naked Lunch. The late trilogy is genre fiction. Burroughs, the cut-up writer, is a crazed, i.e., obsessed, slasher, like Jason Voorhees, wielding a scissors or Stanley blade instead of a machete. Burroughs sought to rip all rational thought to shreds, not nubile co-eds. And think of Burroughs as Benway in Brookner’s documentary standing over a corpse in an operating room splattered with blood. Balch’s Horror Hospital indeed. In addition, Burroughs narrated Haxan, a documentary on witchcraft as well as Poe’s horror classic The Masque of the Read Death. The cut-up might be Burroughs’ greatest affinity with the horror zine. The cut-and-paste aesthetic of horror zines comes from many sources, such as Dada and Punk, but Burroughs fits in there prominently as well. Perhaps nowhere are Burroughs’ ties to horror and fantasy more evident than in his collaborations with Malcolm Mc Neill in Ah Puch Is Here and in Cyclopsmagazine in the 1970s. I wonder to what extent the publishers of the horror zine boom of the 1980s were aware of Burroughs’ work with Mc Neill. It is possible. After all, Screw published a glimpse of the full project in 1977, the dawn of the horror zine boom.

Thinking of Nova Express, Bill Landis’ Sleazoid Express, by all accounts one of the highspots of the horror zine in terms of writing style and world view, comes to mind. Is the “Express” a nod to Burroughs as well as a nod to tabloid journalism? In Landis’ case, the connection would be to Junkiemore than Nova Express or Ah Puch. Landis walked the walk and talked the talk. His writing is gonzo in nature and, like Burroughs and Thompson, he was an outlaw writer. Heroin played a large role in the Landis aesthetic. In Sleazoid Express, Landis documented the dying culture of Times Square sleaze, funk and grit before it was washed away by Giuliani and turned into a Big Apple Disneyland. InJunkie, Burroughs captures a dying Times Square subculture that came under assault by post-WWII moralists. Likewise Burroughs cherished the lost worlds of rural and pre-WWI sleaze as captured by Jack Black in You Can’t Win. To what extent was Landis intimately familiar with that book as well as the work of Burroughs?

The real common ground between Landis and Burroughs - and what makes their visions so unique and personal - was less their personal experiences with junk and junk culture, but the fact that they were awash with nostalgia: a longing for a bygone or rapidly dying era of decadence. The entire horror zine world is one of nostalgia. Few writers document the power and allure of nostalgia as well as Burroughs. Nostalgia is the opiate of the artist.

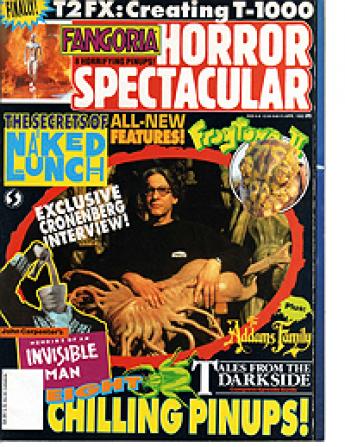

If Bill Landis was not directly influenced by Burroughs, horror auteur David Cronenberg most definitely was and is. Rabid,Scanners, Videodrome, The Fly. These films and others are clearly Burroughsian. Cronenberg’s fascination with Burroughs is well documented, whether it be in Jack Sargent’s Naked Lens, Beat Cinema or freely discussed by Cronenberg himself in Cronenberg on Cronenberg as well as in numerous interviews. Cronenberg got his start in the horror/exploitation genre, which he injected with a Burroughsian worldview of viruses, paranoia, addiction, and information overload. His movies were hotly discussed in horror zines, and Naked Lunch with its special effect creatures, like the Mugwump, was no exception.

I was studying abroad in London in early 1992 as the hype for Cronenberg’s adaptation hit a fever pitch. I distinctly remember picking up a copy of Cinefantastique along with a copy of Viz, and an issue of Club and Penthouse International in an underground newsstand. I still have the Club and the Penthouse, but seem to have misplaced the others. Priorities!!! Cinefantastique featured the latest Star Trek retread on the cover; a movie I thought was incredibly stupid and unnecessary. Yet I did not feel the same about the latest Hellraiser opus, which was splattered all over the horror zines of that Spring. I was in a Clive Barker phase at the time and had eagerly looked forward to Nightbreed, which starred Cronenberg in a decidedly nasty turn as Dr. Decker. Cronenberg wrote the script to Naked Lunch during his acting gig. Perhaps he channeled Dr. Benway.

Much of the press about Naked Lunch centered on how Cronenberg managed to capture what for years had been considered impossible to memorialize on film. Cronenberg made a point not to rely on computer generated effects to re-create the look and characters of Interzone. Flipping through the pages of Fangoria, it is clear that the tide was changing and that Naked Lunch was the end of an era in filmmaking. The film version of The Lawnmower Man represented the future in more ways than one. The adaption of King’s short story was dominated by blue screens and generated by programs crunching a series of ones and zeros. Terminator 2 was yet another example that computers were the future of the horror and action movie and the puppet-based effects of the past were facing their Judgment Day. In this changing FX landscape, the Mugwumps and mutant typewriters of Naked Lunch were physical objects created by hand by the masters at CWI. The actors could touch them, hear them speak. They could violate the actors’ space or even violate the actors physically. Peter Weller states, “Naked Lunch was very easy to do as far as special effects were concerned, because most of them were done live on the set. When I was doing Of Unknown Origin, for example, I never saw a rat for the entire shooting! I was obliged to try and imagine it. For Naked Lunch, everything was before me, and I could talk to it as if it were another actor.” Cronenberg strove to give his creatures a sense of depth as well as a degree of humanity. They were mobile, speaking characters in the film. The Clark Nova and the Mugwump become Lee’s buddies.

Looking back on some of those articles now, I see a relationship between the special effects ofNaked Lunch and the printing technologies of the Mimeograph Revolution and horror zines. Both are old school and time-consuming and require a degree of physical interaction with the materials. Manipulating a mimeograph forced one to get intimate with the machine and get one’s hands dirty. The cutting and pasting of copy for xeroxing is another example. Hands sticky with rubber cement and newsprint. The images of Lee frigging off his mutant typewriter come to mind. In addition, receiving a constructed object in the mail creates a physical and intellectual intimacy, a bond, which the internet and email cannot match. E-zines and blogging permit greater speed of production and ease of distribution but sacrifice the depth and humanity that Cronenberg and Weller speak so passionately of.

All this reminds me that an interesting archive could be gathered by focusing on Burroughs and film. Just thinking off the top of my head, it could include Burroughs books, such as The Last Words of Dutch Schultz, or his script for Towers Open Fire in Film #35. Digging deeper and spending a bit more money would lead to the aborted scripts for Naked Lunch and Junkie from the 1970s. Also included would be reviews or advertisements dealing with the cut-up films, the Burroughs documentaries, or films such as Beat, Kill My Darlings, or On the Road. To say nothing of the movies Twister, Wax or Drugstore Cowboy in which Burroughs starred as an actor. Movie ephemera, like posters and press kits for all these films, fit in nicely as well. The coverage of Naked Lunch in horror fanzines would form a secret torture chamber within this larger, possibly limitless, library. For example in the spring of 1992, the Naked Lunch movie was featured at least four times in Fangoria and Cinefantastique. There are no doubt others. For example Wet Paint #34 presented an article on Naked Lunch along with an image of a Mugwump on its cover. I have been unable to locate a copy quickly. All this begs the question to what extent was Burroughs featured in horror zines both before and after Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch? Anybody out there know of any horror zines that mention William Burroughs? What horror zines can be called Burroughsian? Raw Virus? What else can be dug up from the grave? What Famous Monsters lurk in your attic, closet or basement? Let me hear you scream.

***

Posted on Reality Studio, presented here by the author. Pictures: Reality Studio.