Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Suffragist Literature and The Private Library

By L.D. Mitchell

On 14 July 1848, an obscure newspaper in upstate New York, the Seneca County Courier, ran a small ad that launched a movement:

WOMAN'S RIGHTS CONVENTION - A Convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women, will be held in the Wesleyan Chapel, at Seneca Falls, New York, on Wednesday and Thursday, the 19th and 20th of July, current; commencing at 10 o'clock A.M. During the first day the meeting will be exclusively for women, who are earnestly invited to attend. The public generally are invited to be present on the second day, when Lucretia Mott, of Philadelphia, and other ladies and gentlemen, will address the convention.

The women's suffrage movement that was launched at the Seneca Falls Convention did not occur in a vacuum. Suffrage (the right to vote) had been extended to women in various places and at various times throughout history. In fact, women's suffrage often preceeded universal suffrage, the effect being that only women of certain classes or races sometimes won the right to vote. (In medieval France, for example, voting for city and town assemblies was open only to heads of households, though gender was irrelevant. During Sweden's so-called age of liberty from 1718-1771, only women who were tax-paying guild members could vote.)

The U.S. movement would last for seven decades and produce an enormous body of literature. This literature is widely collected.

Histories

One of the most popular ways to collect this literature is to focus on histories of the movement. Arguably the most desirable of all such histories is The History of Woman Suffrage, published in six volumes over nearly half a century (1871-1922). The first three volumes were edited by Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Anthony was the instigator for the project, believing that if the movement's history was to be accurately recorded, the participants themselves would have to record it. As Sarah Baldwin has pointed out, when it became apparent that the venture could not succeed purely as a commercial endeavor, Anthony (who had tirelessly raised money for the project from a wide range of contributors), took over the copyrights and she and her assistant, Ida Husted Harper, continued to gather material for future volumes.

The U.S. movement was never monolithic (a fact keenly felt by many African-American women), and this is reflected in the six volumes under discussion. Anthony, Stanton and Gage (all of whom were members of the National Woman Suffrage Association) had solicited contributions for the volumes from Lucy Stone, a member of the more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association, but wound up publishing very little about the latter organization. Thus, the early history of the movement is skewed, a fact which later histories would take pains to correct.

The two organizations, which had organized independently in 1869 due to major differences over strategy, would merge decades later, in 1890, a merger that would cause the movement as a whole to become more conservative in later decades. This is notable in the final three volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage, as these feature a distinct "lack of fervor" compared to those edited by the early triumverate.

Biographies

The suffragist movement in the United States, like similar movements elsewhere (most notably in Great Britain), was organized, promoted and led by a wide range of women, as well as a number of men. Because the early suffragists in Great Britain did not produce their own history of the movement (as did Anthony, Stanton & Gage in the United States), it's not uncommon for folks collecting biographies and autobiographies of U.S. suffragists also to collect those of suffragists in other countries as well.

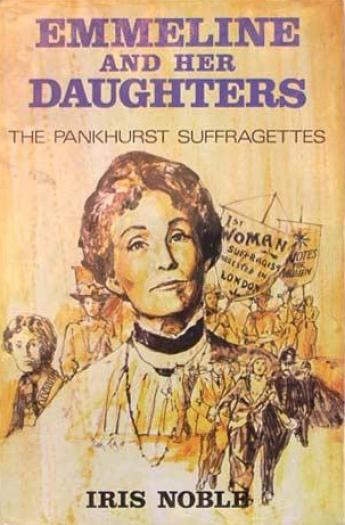

Emmeline Pankhurst and her followers in Great Britain preferred the term suffragette, not suffragist. As was the case in the United States, the movement in Great Britain was not monolithic. Pankhurst's organization, the Women's Social and Political Union, was very militant, more militant even than Anthony's National Women's Suffrage Association (NWSA). This militancy, which included prison hunger strikes and arson, among other tactics, eventually would lead two of Pankhurst's own daughters to resign from the organization. Among the many notable suffragettes who followed Pankhurst, one finds Frances Parker, niece of Lord Kitchener; Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton, whose paternal grandfather penned an immortal ode to nights "dark and stormy;" and the Scottish poet Helen Cruickshank.

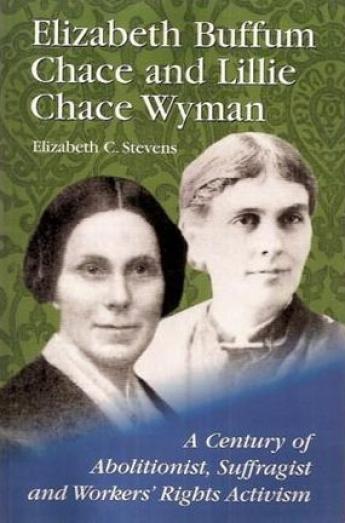

The suffragist movement in the United States produced a large number of notable biographies and autobiographies, especially for Anthony, Stanton and fellow NWSA members. Fortunately, in recent decades the less militant side of the U.S. movement has received an increasing amount of biographical attention.

Some of the more interesting biographies are collective rather than individual (one frequently encounters such collective biographies where several members of the same family engaged in similar types of activism).

Biographies and autobiographies of movement members, as well as histories of the movements themselves, are not the only types of books that collectors of this material seek for their shelves. The philosophies that underlie such movements also are important.

Philosophies

In addition to histories of the suffragist movement(s), and biographies of the movement's many leaders, supporters and (sometimes) detractors, most folks building a private library focused on such movement also add to their bookshelves a wide range of works regarding the philosophies that underpinned this movement.

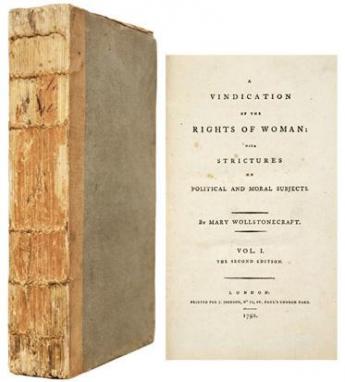

This title, by the mother of Mary Shelley (author of Frankenstein; or the Modern Prometheus), is arguably the most desirable of all such works of "philosophy," and is almost never found in anything approaching fine condition (in fact, the above image depicts the second edition).

Mary Wollstonecraft saw education as the key to the advancement of women's rights, a theme she had briefly foreshadowed in her first book, Thoughts on the education of daughters: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life, published in 1787. Her travels in France during the last decade of the 18th century significantly reinforced this belief.

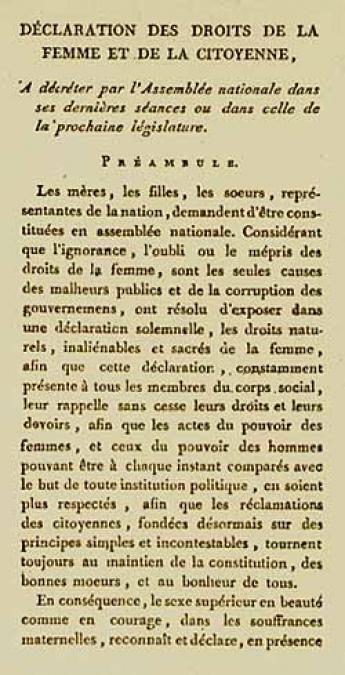

Folks often are surprised to discover that women's rights were broader in the Islamic world in the 7th century than they would be in Western Europe until the 19th century. The advent of the so-called Age of Enlightenment in 18th century Europe led the French playwright and political activist Olympe de Gouges to declare, in her 1791 work Declarations des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne(Declaration of the rights of woman and of the [female] citizen): [The French Revolution] will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society.

This important work is very difficult to come by, and it is only recently that de Gouges has been treated to a long overdue biography:

In the United States, other early philosophical underpinnings of the suffragist movement are found in works like Emma Willard's An Address to the Public; Particularly to the Members of the Legislature of New-York; Proposing a Plan for Improving Female Education (1818); Sarah Grimké's Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women (1st published in book form in 1838); and Margaret Fuller's Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1st published in book form in 1845).

Fiction

The philosophies underpinning the women's suffragist movement(s) often were more eloquently and poignantly stated in fiction rather than in essays.

As Sarah Baldwin has suggested, as early as 1868 fictional works like Louisa May Alcott's Little Women (or Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy) began to reflect the belief that women had talents and abilities they should pursue to become full, mature adults.

This view was presented with particular force in fictional works like Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House (1879), in which the protagonist eventually leaves her family in order to become "a real person: After making a great sacrifice on behalf of her husband, who (it turns out) is not the great and noble being that she had long imagined him to be, Nora realizes that

“... before all else I am a human being, just as much as you are - or, at least, I will try to become one. I know that most people agree with you, Torvald, and that they say so in books. But henceforth I can't be satisfied with what most people say, and what is in books. I must think things out for myself and try to get clear about them .... I had been living here these eight years with a strange man, and had borne him three children - Oh! I can't bear to think of it - I could tear myself to pieces! ... I can't spend the night in a strange man's house.”

To say that audiences of the day were shocked by a woman mouthing such words is a very considerable understatement.

Imagine their surprise, then, when just a few years later (1892) an African-American woman penned a groundbreaking novel that addressed not only the plight of women, but the insidious effects of racism as well.

Abolitionist and poet Frances Harper's seminal work addresses its multiple themes by focusing on a female protagonist of mixed race.

More such fiction followed in short order. Charlotte Perkins Gilman explored the previously taboo subject of post-partum depression in The Yellow Wallpaper (1st published in book form in 1899). Gilman, who first achieved fame with her 1898 work Women and Economics – A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution, is recognized - as are most of the women discussed in our three previous posts on this subject - by enshrinement in theNational Women's Hall of Fame.

An even more groundbreaking work also was published in 1899, a fictional work that had the temerity to suggest that sexuality might be important to a woman realizing her fullest potential as a human being. Such works continue to be published down to the present day, since the battle for women's rights, like the battle for other civil rights, is never fully won....

(Posted in four parts on The Private Library. Presented here by permission of the author.)

Suffragist Literature and The Private Library

>>> Part 1

>>> Part 2

>>> Part 3

>>> Part 4

You are interested in women’s liberation?