Buried Books - The Cairo Genizah

By Linda Hedrick

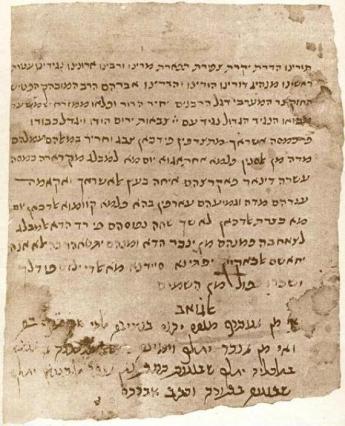

A genizah (plural genizot) is a storeroom or depository in a Jewish synagogue or cemetery specifically meant to hold worn-out books and documents in Hebrew before they are properly buried. Jewish law forbids throwing anything away that contains the name of God. Personal letters and legal contracts often opened with an invocation of God. A genizah may also contain secular writings in other languages that use the Hebrew alphabet. Many documents were written in Aramaic using the Hebrew alphabet.

Normal practice is to remove the contents of the genizah on a periodic basis and bury them in a cemetery. The most famous for both its size and contents is the Cairo Genizah. Almost 180,000 Jewish manuscript fragments were found in the genizah of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo. More fragments were found in the Basatin Cemetery east of Old Cairo, and some old documents were bought in Cairo in the late 19th century.

The first European to "discover" them was Simon van Geldern (an ancestor of Heinrich Heine, the 19th century poet) who visited the synagogue about 1752. Later European travelers explored the genizah, but not until they were brought to the attention of Solomon Schechter at Cambridge University did they receive proper scholarly attention. Schechter acquired many of the documents.

The whole body of documents, which includes books, letters, and legal documents, was written from circa 870 CE to as late as 1800. These writings are important in the reconstruction of the economic and social history of the area between 950 CE and 1250. The Judaic scholar Shelomo Dov Goitein, a famous ethnographer known for his research on Jewish life in the Islamic Middle Ages, made an index of the time period that the documents cover, and it included 35,000 everyday people, as well as prominent ones such as Maimonides (the 12th century Jewish scholar, philosopher, and physician) and his son Abraham. The documents mention professions, goods, and cities of trade and contact from Kiev to India.

Most primary documents extant are of momentous events and important people. These are related to ordinary people, which make them unique. Linguistically they also have great importance, as they illustrate the history and changes within various Arabic dialects.

Many unique Arab manuscripts were found, such as a pharmacological text of an 11th century doctor. A 10th century letter provided the earliest evidence of a Jewish community that existed in the Ukraine. There are also Yiddish letters and poems from the 13th to 15th centuries.

The collection is today dispersed among several universities. The Taylor-Schechter collection at Cambridge has almost 193,000 fragments. There are 31,000 pieces at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. The John Rylands University Library in Manchester has a collection of over 11,000 fragments that are being digitized for an online archive.

The continuing study of the documents offers rare opportunities to see life in those times in that area of the world. A window into the past, what new discoveries will be made from these promises to take the guesswork out of history?

The Taylor-Schechter Genizah Research Unit has an excellent site. The Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image has many of these fragments available online.

The article was published on Cerebral Boinkfest. It is presented here by permission of the author. (Images courtesy of the Cambridge University Library and Wikipedia)