Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Peter Harrington Rare Books (UK)

Women's Work: women in Economics, Politics and Philosophy | New blog from Peter Harrington

Virginia Woolf’s words about Mary Wollstonecraft – “we hear her voice and trace her influence even now among the living” – are as applicable today as they were in 1932. Often considered to be the mother of modern feminism, Mary Wollstonecraft was a philosopher, war reporter, political and social activist and an educational reformist. A Vindication of the Rights of Men was the first in a series of retaliatory pamphlets sparked by the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). In the form of a letter addressed to Burke, Wollstonecraft utilised Burke’s own style and language to point out the inconsistencies of his arguments, to attack his insistence on the importance of rank and privilege and object to his description of ordinary people as the “swinish multitude”. Many of the arguments which find fuller expression in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794) have their basis in this text. Her argument that many of Britain’s problems are rooted in the unequal distribution of property still rings particularly true.

The copy is interestingly bound with the reaction of another female writer, Catherine Macaulay, to Burke’s Reflections. An accomplished and celebrated historian, and the first Englishwoman to become so, Macaulay’s objections to Burke’s assessment of the French Revolution were as impassioned as Wollstonecrafts, and lead to a brief correspondence between the two women.

Later known as the Female Society for Birmingham, this album is an early example of using shock tactics for the purpose of fundraising. It was intended to “waken attention, circulate information, and introduce to the notice of the affluent and influential classes… acknowledge of the real state of suffering and humiliation under which British Slaves yet groan” (Annual Report 1825). Donations collected were sent to anti-slavery groups in Britain or overseas.

Unlike the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (or the Anti-Slavery Society) (established 1783), headed, amongst other leaders, by William Wilberforce, many women’s anti-slavery movements called for the immediate emancipation of all slaves, as opposed to the gradual phasing out of the trade. Women were denied membership to the Society for fear that they would push for a more radical action against slavery than many of the male leaders considered prudent. However, fundraising efforts of women’s groups such as those achieved by a publicity album such as this meant that over a fifth of the organisation’s financial support came from women. Despite this, women continued to be excluded from leadership roles of prominent anti-slavery organisations into the 1800s and the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves was set up in response to this. Elizabeth Heyrick was one of its founding members. In 1824 she published a pamphlet entitled Immediate not Gradual Abolition which set out the case for the total outlawing of slavery, rather than simply a gradual shift towards discontinuing the trade. She addressed the root of the problem which was that “The West Indian planters, have occupied much too prominent a place in the discussion of this great question. The abolitionists have shown a great deal too much politeness and accommodation towards these gentlemen.” Wilberforce’s society attempted to suppress this pamphlet and Society leaders were instructed not to speak at the meetings of women’s groups.

In 1830, the Birmingham Society submitted a formal call to the Anti-Slavery Society to begin campaigning for the immediate abolition of slavery, threatening to withdraw its funding if the male leadership ignored their demands. The Society eventually agreed to drop the words “gradual abolition” from their aims.

Heyrick never lived to see the passing of the Abolition of Slavery Act in 1833 and women continued to be excluded from the conversation about international slavery. In 1840, an attempt to keep women delegates from appearing at the World Anti-Slavery Convention led abolitionist Anne Knight to begin campaigning for women’s rights. In 1847 she produced what is believed to be the first work for women’s suffrage.

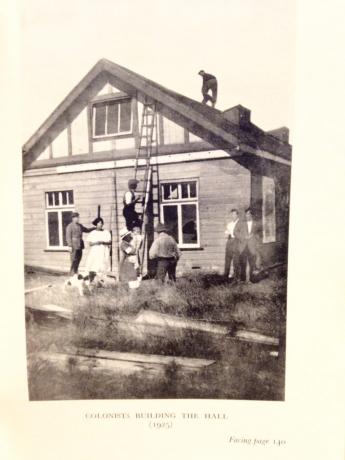

Nellie Shaw, an anarchist feminist seamstress from Penge in Bromley, is a figure ripe for recovery from relative anonymity. She was one of the founding members of the Whiteway colony, a utopian community of free-thinkers established in 1898 in the Cotswolds. Their values were based on socialism, vegetarianism, self-sufficiency and a rejection of property laws. The deeds to the 41 acres of land originally bought by the colonists were burned on the end of a pitch fork as a symbolic gesture.

A member of the Fabian Society and the Independent Labour party, Shaw founded Whiteway with a group of friends after abandoning a previous communal living project in which she had encountered problems with its classist and sexist values. Whiteway was conceived as a community which would adhere to the values of gender equality and relative sexual freedom. Shaw’s account of the community’s early days is told with humour and tolerance, noting the various imperfections and absurdities of its initial members and detailing some of the problems of communal life.

The colony’s experimental style of life was greeted with suspicion and speculation from outsiders. It was rumoured to be a nudist colony, and sightseers would often arrive to try and ascertain whether this was true. In the 1920s, rumours of ‘free love’ and of the colony being home to dangerous “free thinkers and refugees” lead to it being seen as a national security risk. The police engaged a husband a wife to go undercover in the colony and report back on the lifestyles of these undesirables, but, although they couple alleged they had witnessed “promiscuous fornication”, no evidence could be produced.

Nellie Shaw remained at Whiteway for the rest of her life, writing her account of it thirty years after she first arrived. Although marriage was in no way prohibited amongst colonists, Nellie chose to exist in what she called a ‘free union’ with her partner Francis Sedlak, who was described in his obituary as “rebel Czech” and “Hegelian philosopher”. The decision of a number of its members to do likewise fuelled further prejudice about the community, leading to one woman being accused of adultery for taking another partner after her first relationship was ended by mutual agreement. Problems also arose at Whiteway in the domestic arrangements: Shaw relates that, while “The women do exactly the same kind of work as the men, and do not find it too tiring”, the washing and cleaning was left to the women alone.

While the deal seems inevitably to have been slightly harder on the female members of the community, Shaw’s vision of equality, shared labour and life lived for the benefit of the group is inspiring and instructive. Whiteway contains the text of a she gave to a young women’s group in Croydon shortly after the founding of the colony. She paints a romantic picture of the colony’s rural setting – its “delightful valleys and well-wooded hills” – she does not obfuscate the challenges of community living:

Of course, there is another side to all this. Wet days, especially wet washing days, are very trying. Endeavouring to make old trousers into new knickerbockers, darning impossible socks, running out of some necessary item of food … but worst of all … finding in ourselves unexpected weak places, being impatient of other people’s failings, forgetting our own…

“But”, she tells us, “we must have patience and learn.” The colony at Whiteway survives to the present day.

This article was published on 26 October 2016 by Peter Harrington Antiquarian Booksellers and is presented here by permission of the author, Rachel Chanter.