Actualités

UK's Times deputy literary editor, James Marriott, confesses "Bibliomania"

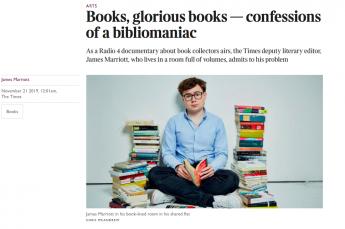

Extract from The Times, 21 Nov 2019:

I have hundreds of books; I’ve been buying them ever since I had pocket money. My first haunt was Keel Row Books in North Shields. It is one of the world’s perfect places. I still dream about being 16 again, spending the summer holiday perched on top of the wooden stepladder in the shop’s upstairs room with the warm sun spilling through the window and the sound of the breeze in the horse chestnut trees in the churchyard opposite.

...

But why am I getting so emotional? I don’t feel dreamy and nostalgic thinking about where I bought a DVD or my iPhone. Why do books make me feel this way? And why do I own so many? The “disease” of bibliomania was most famously diagnosed by the book collector Thomas Frognall Dibdin in Bibliomania; or Book Madness. Dibdin provided case studies. Consider poor Richard Heber, an 18th-century gentleman who filled eight houses with his collection. “No confirmed drunkard, no incurable opium-eater had less self-control,” Dibdin noted sadly. With characteristic insanity Heber once remarked that “no gentleman can be without three copies of a book: one for show, one for use and one for borrowers”, but Heber got off lightly compared with the Tudor scholar Roger Ascham, who, Dibdin says, “died in the vigour of life . . . I suspect, in consequence of the Bibliomania”.

I’m lucky (or cursed, perhaps) to know many modern bibliomaniacs thanks to the years I spent working for Bernard Quaritch, a firm of antiquarian book dealers. Our offices in a salmon-pink Mayfair townhouse were the stuff of bibliomaniacal daydreams: teetering piles of 17th-century verse, small landslides of radical pamphlets, locked cupboards of illuminated manuscript fragments. One of our most important clients was the American lawyer Robert Pirie, who, as a young man on military service in Germany, once drove 15 miles in an army Jeep to secure a copy of John Donne’s Devotions. Later in life Pirie would pay $150,000 for a single letter by Donne. The auction of his books after his death was so dramatic that we live-streamed it in the front room at Quaritch, drinking champagne as we watched his books sell for fantastic sums (the collection fetched almost $15 million).

...

I think any of the rare book collectors I know would disagree with that statement, but there may be some truth in it. “Books were the easiest and cheapest way to get close to antiquity,” explains an old Quaritch colleague, Andrea Mazzocchi, 37, who is not only one of his generation’s most skilled rare book dealers, but also the owner of 20,000 books (quite a feat for someone living in a small flat in London). Incidentally he attributes his obsession to watching Roman Polanski’s film The Ninth Gate (about a rare book dealer seeking out demonic texts) as a boy — “I was just in rapture,” he remembers. His enthusiasms are different to mine: the “beautiful bindings” of 16th-century Italian books “are simply fantastic”, he says. He loves typography and annotated editions and bookplates.

To access the full article, please follow this link