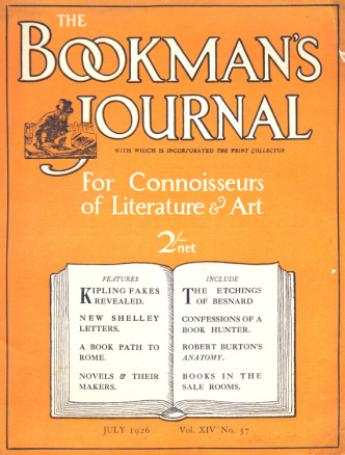

Actualités

The Confessions of a Book-Hunter â 1926

So far, so good – the opening paragraph of an article headed The Confessions of a Book-Hunter, which appeared in the July 1926 issue of The Bookman’s Journal. But as I read on, I began to have my doubts – this didn’t really sound as if it had been written by someone familiar with, or wholly at ease, with the language of books. The sticking-point came with the author’s tale of his having discovered “some years ago” that black tulip among books, a copy of Shelley’s anonymous “lost” first book, written with his sister, Elizabeth – Original Poetry, by Victor and Cazire (1810) – in a “particularly dirty bookshop, small, dark and dusty” in the backwaters of Hastings. He had come out without any money on him, but having hurried home to get some, returned to find that the book been sold for threepence to the book-collector Mr Nicholls [sic] of Barnesbury [sic]. After the death of this collector, the book was subsequently sold at Sotheby’s for £600.

This story cannot possibly be true. Fake news from 1926. The book-collector Adolphus Frederick Nichols (1811-1902) of 25 Arundel Square, Barnsbury, is thought to have acquired his copy of Original Poetry, by Victor and Cazire for sixpence (almost certainly without realising it was by Shelley and his sister) on November 23rd 1876 (before he lived in Barnsbury). Nichols died on 19th February 1902. This book was then indeed sold at Sotheby’s – on November 2nd 1903, and indeed for £600 – then a record price for any nineteenth-century book – but the author of these fake Confessions was at that time only five years old. And the book had in any case ceased to be a “lost” one even earlier – before the author of these Confessions was even born – a copy inscribed by Shelley to his cousin and fiancée, Harriet Grove, was discovered in the hands of her niece in Dorchester in late 1897 or early 1898 – the first to surface of I think just four copies now known – one in the Ransom Center (the Harriet Grove copy), one in the Huntington (the Nichols copy), one in the British Library (the Wellesley copy discovered in 1903, soon after the sale of the Nichols copy), and one in the Pforzheimer – this last acquired as recently as 2014 (such things still happen) – see A Black Tulip Comes to the Pforzheimer Collection. There is a good account of the discovery of the first three copies in the Burlington Gazette (the supplement to the Burlington Magazine) for December 1903, pp.2-4.

The author of these Confessions was one Edward J. Lavell, a journalist by profession (with all that this implies in terms of veracity) – and I’m certain that it is nothing more than an entertaining piece of journalistic fiction, stitched together from various sources. It is by no means impossible that he did own some of the books he lists amongst his triumphant discoveries – but I beg leave to doubt it. On the other hand, I have by now become interested in Lavell. He was born Joseph Edward Lavell on 27th August 1898 at Wallasey in Cheshire, later in life transposing his forenames. He was the only child of the Irish financial journalist Mathias Lavelle (usually spelt with a final ‘e’) and his wife Mary Croshaw, who had married in 1897.

By 1921 Edward J. Lavell was working as a journalist in Ramsgate, joining the freemasons in that year, while the 1933 edition of Who’s Who in Literature and other similar interwar works of reference fill in some further background. He had contributed not just to The Bookman’s Journal, but also The Bolton Journal; The Bolton Evening Chronicle; The Kent Argus; The Irish Independent; The Anglo-Scottish Press; The Fascisti Bulletin; Pitman’s Journal; The Liverpool Evening Express, on which he was sub-editor from 1929, and the Manchester Evening Chronicle. He was currently living in Manchester (later in Southport) and was the editor of Home Topics, published by the New Catholic Press, a magazine begun in 1923 on the back on an earlier publication called The Catholic Home Journal, which had commenced publication in 1905. His chief recreation was listed as travel – and records survive of voyages to Cherbourg and Santander in 1925 and 1926.

He married Lucie Cottingham (1906-1991) at Wallasey in 1938 and the couple were living, with his wife’s elderly mother, on Caithness Drive in Wallasey the following year. Lavell’s occupation on the emergency 1939 Register is mostly illegible, but the words “war correspondent”, “Spain” and “Albania”, seem clear enough.

During the Second World War he contributed a number of occasional articles to the Liverpool Echo – an entertaining and morale-raising piece on the Droll Fellows from Albion: The Strange Englishman; “says little, grouses and deprecates, but sees things through”; a very good article on the pernicious influence of the “cockney” received pronunciation being so heavily promulgated by the BBC; an amusing piece on a wartime bus-conductor’s opening gambit of “Any more for anywhere? Special cheap tickets for Utopia”; articles on Silesia, Czechoslovakia and Japan; on H. G. Wells and the Atomic Bomb; on post-war planning, and on the forthcoming 1945 election, etc., but unless a letter written from Tewkesbury to the Birmingham Daily Post in 1966 on the Rhodesia question is from the same hand, that would appear to have been the end of his journalistic career. His wife died at Wallasey in 1991, but I have been quite unable to discover when or where Lavell himself died.

His piece in The Bookman’s Journal ends on a slightly plaintive note: “There is a poetic justice in this world. A publishing firm has just accepted my first novel, and maybe when I am dead copies will find their way to some dusty bookstall, and there be spurned by the bibliophile”. This is intriguing. According to the various reference books, Lavell was the author of Treasure Trove and Other Stories (Thanet Publicity Agency, 1922); Memoirs of the Abbe Brouillard (Catholic Press, 1924); The Vision Beautiful (Anglo-Scottish Press, 1925); The Blue Danube (a serial), 1928; Mr Povy, A Seventeenth Century Panorama(short stories), and Italy, a musical drama.

There is a copy of the first of these in the British Library, but nowhere else, as far as I can tell. As for the rest, I can’t find a single copy or even a trace of them in any of the world’s major libraries, and certainly not in the market-place. I suppose this might make them technically rarer even than the Shelley book – although I suspect even a seasoned bibliophile might well still spurn them. But then again – he may simply have made these titles up along with everything else, to boost a rather slender C.V. Do let me know if you come across a copy of any of them.

I am extremely grateful to my friend and neighbour Gillian Neale, currently studying for a Masters in the History of the Book, for discovering this curious article and letting me have the loan of her copy.