Actualités Associazione Librai Antiquari d'Italia Govi Alberto Libreria di Fabrizio Govi

Rare Books Worldwide - A Short History of the Book and Bibliophily in Italy

By Fabrizio Govi

In a series of articles antiquarian booksellers and rare book collectors from all parts of the world write about bookselling and collecting in their country. Part 1, written by rare book expert Fabrizio Govi is dedicated to the history of the book in Italy.

In 1464, the German monks Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz arrived at the Benedictine monastery of Subiaco with their precious cargo of metal punches and matrices for casting movable type. They had been apprentices of the Mainz workshop of Peter Schöffer. With their arrival the extraordinary adventure of printing in Italy began.

From Subiaco the two moved to Rome, where they established their press in the house of the noble Piero and Francesco de’ Massimi, and began collaborating with Giovanni Andrea Bussi, the first humanist to realize the extraordinary cultural relevance of the new invention.

In Italy the new media flourished like nowhere else in Europe. In a few decades, Italy, thanks to its extensive sales network and the presence of numerous and prestigious universities, became a great center of evolution of the press and eventually surpassed Germany itself: 4157 editions were printed in Italy from 1465 to 1550, as apposed to the 3232 issued in Germany, 998 in France and 395 in the UK. Considering an average press run of about 400 copies, ranging from the 200 at the very beginning to the over thousand copies of the end of the century, we may calculate that over 15.000.000 books were produced in the peninsula during that period of time.

The press found in Italy fertile ground for many cultural and economic reasons. As a matter of fact, the humanist movement quickly understood the importance of the new technology for the transmission of the classical texts, as well as for the propagation of their new ideals.

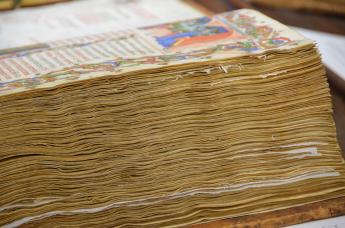

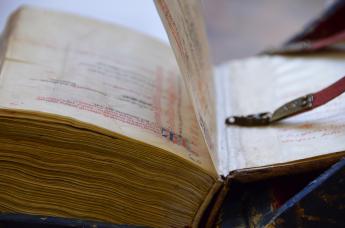

This cultural revolution, however, had began much earlier, in the mid 14th century through the figures of Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374) and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), who can be considered the first two bibliophiles of the modern era. They were the first who really realized the significance of recovering the works of classical authors and started gathering and copying manuscripts with the purpose of establishing a new kind of library, not only based on the Holy Scriptures and on the Church Fathers. Petrarch’s library can be considered the first modern library. From then on, for around a century, philology and book collecting went together, to aid in finding and copying the most faithful manuscripts of the ancient texts.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the goal of gathering together classic texts passed from Petrarca and Boccaccio to the first humanists, who travelled throughout Europe searching for new texts to discover or more reliable copies of known texts. Two events, in particular, turned out to be crucial for the development of humanism and its spread outside of Italy: the Council of Constance (1414-1418) and the almost contemporary Councils of Basle and of Florence (1431-1445).

On those occasions, humanists like Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459) not only made landmark discoveries in the monasteries of Northern Europe, but also contributed greatly in widely spreading the new humanistic ideals beyond the Alps. Moreover, Florence was then the meeting place of Western and Byzantine culture, permitting through the activity of key figures like Cardinal Basilios Bessarion (1408-1472) the promotion of the study of the Greek and the formation of the first significant Greek library in Western Europe: the manuscripts that Bessarion had gathered and brought to Venice, saving them from the destruction of Constantinople (1453), and which were in fact given to the city and formed the first core of the Marciana Library.

In Florence, the great bibliophile and philologist Niccolò Niccoli (1363-1437) was very active in copying and finding ‘codices’ for his personal collection, the most remarkable private library of his time, and for Cosimo de’ Medici (1389-1464), whose family library, together with the collection of the monastery of San Marco, formed the Biblioteca Mediceo-Laurenziana.

But the prototype of the Italian bibliophile and book collector of the time was Pope Nicholas V (1397-1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, whose amazing collection of manuscripts (mainly bought from the Florentine bookseller Vespasiano da Bisticci, 1421-1498), formed the Vatican Library, which was formally established a few years later, in 1475.

In those years almost every Italian duchy gathered an important collection of books, initially formed as the Duke’s private library and then become public. This is the case for instance of the Este library, which in 1598 was moved from Ferrara to Modena.

Italy continued to maintain the primacy of book production in Europe until at least the middle of the 16th century, when the restrictive reforms of the Council of Trent were imposed throughout the country, exacerbating the slow but inexorable process of decline that the most acute contemporary observers had already begun to perceive and had reported since the descent of Charles VIII, king of France, in 1494. This event gave start to the ruinous wars of conquest and to the foreign occupation of a large part of the country, which lasted unbroken until 1861.

From the mid 16th century the primacy of bibliophily left Italy and settled in France. The key figure that best expresses this transition is Jean Grolier (1490-1565), the great French bibliophile who lived for many years in Milan, who maintained contact with many of the major Italian humanists and collectors of the time.

But, since every radical mutation takes place gradually, in Cinquecento’s Italy we can still trace some very important figures in the history of bibliophily and book collecting, like Tommaso Maioli (also known as Thomas Mahieu, ca. 1500-1565), Demetrio Canevari (1559-1625), and Gian Vincenzo Pinelli (1538-1601), whose amazing library partly ended up in the bottom of the sea upon the sinking of the ship that transported it from Naples to Genoa.

In the 17th century a special mention is deserved for the libraries gathered by Cardinal Federico Borromeo (1564-1631), the founder of the Bibliotheca Ambrosiana of Milan, and Antonio Magliabechi (1633-1714), one of the most learned men of his time. Besides, the Accademia della Crusca, whose vocabulary, the first scientific dictionary of any modern language, was first published in 1612, set up a new standard for the Italian tongue and established a literary canon of Italian authors that had great influence on the development of the Italian language, literature and book collecting until the end of the 19th century.

In the Settecento Italy’s economic decadence was an impediment to the growth of the modern book trade that countries like England or France were developing. The accumulation of important libraries, like that of Cardinal Domenico Passionei (1682-1761), was sporadic and linked to the initiative of single individuals. After a long period of decay, the Venice press enjoyed a revival during the century, which was however mainly due to the export towards foreign markets.

In the late 18th and early 19th century Bodoni revived the quality of book production, setting up new standards, that however in Italy were followed only many decades later, after the country reunification, which undoubtedly improved significantly the economic condition of the country.

In the 20th century the flourishing of book production and of the book trade coincided with the development of a eventually unified market, with the improvement of education and literacy, as well as with the birth of avantgarde movements like Futurism.

After the Second World War, the Italian book trade, which had been brought to an international level by Leo Olshki and other booksellers at the beginning of the century, was taken over by ALAI, the first and only professional association of the country and an affiliate of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers since its foundation in 1948.

Generally speaking about the market today, the strongest elements of the Italian book trade have always been the Renaissance book (manuscripts, incunables and early printed books), the scientific book of the 17th century (Galileo, Torricelli, and so on), and some important works from the Italian Enlightenment of the 18th century on economics and politics. The Italian literature of the post-Renaissance period does not enjoy the international allure that the Renaissance and late-Medieval authors continue to have, because of their deep and long-lasting influence on the national literatures of so many European countries. The market today reflects in the value of the books the loss of influence of Italian literature after the golden age, with of course many exceptions. Even the best authors of the 19th and 20th centuries (Nobel Prize winners included) are mainly confined to the national market.

This is true also for the travel book, a field in which Italy lost primacy in the mid-16th century (almost all the major geographical and travel accounts of the early period are written by Italians and/or printed in Italy), as a consequence of the isolation in which the country found itself when the center of the European maritime traffic moved from East to West and from the Mediterranean sea to the Atlantic Ocean. The strategic geographical position of the peninsula, that has been for centuries a natural departure point for traveling towards the East (just think about the Crusades and the Venetian domination before the Turks), became a disadvantage when the main trade of goods and money shifted to the Americas. This was of course reflected in the production of travel books in Italy from the end of the 16th century, with of course the exception of reports from missionaries coming from all over the world.

The market today, in many ways, also mirrors the cultural habits of the past. There is no way to find collections of English books from the 19th century (just to give an example) in historical private libraries in Italy, because nobody at that time read English novels in their original versions. On the contrary it is not impossible to find French books, especially from the 18th and 19th century, as a proof and a consequence of the deep influence of the French language and culture on Italy during those centuries. One final point, the antiquarian book trade in Italy is deeply affected by the most severe legislation in all Europe, which imposes an export license for every book older than fifty years, no matter its commercial value, and obliges the booksellers to keep records in a special book, called a Public Security Book, of all items and all customers whom they deal with (the registration includes not only customer’s full name and address, but also his identity card number and tax code).

In particular, the export license obligation for practically every book hinders the on line trade of low end books and the almost automatic denial of export for all early manuscripts, unaccompanied by the purchase order that should be issued by an institution, is inevitably driving this trade out of the country.

***

Published in the Magazine du Bibliophile.