Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America

"Proof" Prints

Chris Lane

What exactly does it mean when one says a print is a "proof"? While the connotation of this term is clearly positive, it is not always clear what specifically it means. In the world of fine art prints the expression has a quite clear meaning. A proof is an impression of a print pulled prior to the regular, published edition of the print. Within this category there are a couple of sub-categories.

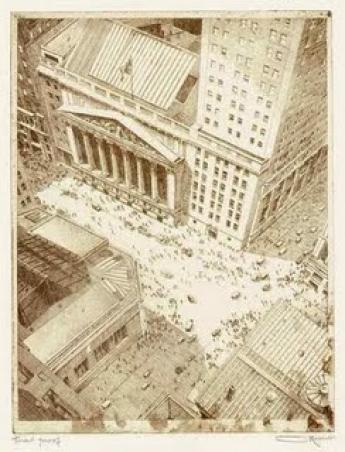

A trial or working proof is one taken before the design on the matrix (plate, lithographic stone or wood block) is finished. These proofs are pulled so that the artist can see what work still needs to be done to the matrix. The Otto Kuhler print above is a trail proof. Once a printed image meets the artist's expectations, this becomes a bon á trirer ("good to pull") proof, meaning that the artist has ok’d the matrix for printing.. This proof is often signed by the artist to indicate his approval and is used for comparison purposes by the printer.

An artist's proof is an impression issued extra to the regular numbered edition and reserved for the artist's own use. Artist's proofs are usually signed and are sometimes marked "A.P." (artist’s proof), "E.A." (Épreuve d'Artiste) or "H.C." (“Hors Commerce,” meaning outside the regular commercial run).

All this is well established, for with fine art prints there is usually a concern that the prints be run off exactly as the artist wants them and that the number of impressions be limited. In contrast, the meaning of “proof” is not nearly so clear for commercial prints. Commercial publishers realized that the positive connotation of the term meant that there was a financial advantage to offering so-called “proofs” for sale. Thus commercial publishers developed other types of proofs to offer to purchasers, generally at higher prices.

A proof before letters (Avant les lettres) is an impression of a print pulled before the title is added below the image. A scratched letter proof is an impression in which the title is lightly etched below the image. A signed proof is one where either the engraver or artist or both signed the print in the margin (that is, with a manuscript signature, not a printed one). The print of Lady Washington's Reception above is a signed proof before letters, with pencil signatures by both the artist and engraver. These are different ways in which publishers created "special" impressions of their prints, ones that were limited in number and so, in theory, worth more.

This is all fairly clear and there are examples of all these types of prints from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, the term “proof” ended up in the nineteenth century being used in a manner which essentially made it meaningless. One can find the term "Proof" on hundreds of examples of some prints, especially for the larger, steel engraved prints from the mid to late nineteenth-century. Indeed, for some of these prints we have found no examples without “Proof” engraved at the bottom. The print of Washington and Family above is one we always find with "Proof" printed in the bottom margin.

One assumes that the publishers of these prints did mean something by engraving “Proof” on these prints, but we have never figured out exactly what. It is obvious that the appearance of this label on the prints was meant as a sales tool, for the term has always been associated with limited numbers and higher value. However, so many prints have this term printed on them that “Proof” does not mean anything like the original meaning described above. It may be that these prints were intended to be “special” impressions issued in “limited” numbers, but certainly the numbers were not that limited nor are the prints really in any obvious way more "special" than the regular edition impressions (assuming there even was a regular edition).

So what does it mean when you find “Proof” in the margin of a mid to late nineteenth-century print? We get a queries about this all the time. The answer we have to give is “not much of anything.” We don't know what specific meaning this term was intended to have by the publishers (if anyone has ever seen anything from a publisher explaining their use of this term, I’d love to hear about it..), and it really doesn’t make any difference at all in price of these prints. I guess if there were two copies available of a print, one with "Proof" and one without, I'd pick the one with "Proof" on it if everything else was the same. However, if there were even a small difference in condition, I'd choose the print in better shape whether a "Proof" or not.

The article was published by Chris Lane on antiqueprintsblog.blogspot.com and is presented here by permission of the author. Thank you very much.