Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Omega Bookshop

Printed Matters: or why own books?

By Angus O'Neill

“Books? Why would I want to own a book? They take up space and gather dust, they're a pain to carry if I move; oh, and I can always get the text from the Internet ...”

Well, at the moment, you often can; but it may not always work like that.

If you buy a printed book, then you own an object. There are likely to be conditions attached, such as a prohibition on rebinding and reselling a paperback; and, of course, you don't normally acquire any copyright over the text, so don't even think of running off a few hundred copies for your friends: but you do now own a physical object, and only under exceptional conditions can anyone legally deprive you of it. Electronic "books" are a different matter. Just because it's on your computer (and we will use this word very loosely to include any of the devices that store electronic text), it doesn't mean it's yours. If you “buy” a book for your computer - the suppliers always use the word "buy", it's so reassuring - what you have is not a book, it's a licence.

This can lead to trouble. First, of course, many of us like to own things; that excellent organization, the Private Libraries’ Association, promotes “the simple pleasures of reading and ownership”. If they'd said “the simple pleasures of reading and licenseeship”, it wouldn't have quite the same force. The thrill of owning and handling an original piece of printed or manuscript material is an experience with which most visitors to this site will be familiar. But there's more to it than that.

As buyers of an electronic text found recently, if the licensor has a change of heart, they can just press a few keys, and next time you open your computer, whoosh, and the text is gone. (The book, with exquisite irony, was Nineteen Eighty-Four ...) In this instance, the vendors dealt with the problem straightforwardly, and refunded the buyers' - sorry, licensees' - money. But one doesn't have to be a conspiracy theorist to see how things could go much more badly wrong.

Rewriting history has appealed to dictators throughout the ages. Even relatively open governments have fallen, are indeed falling, prey to its temptations. How easy it would be just to correct Professor X‘s interpretation of that peace treaty; he didn‘t have all the information to hand, he was getting on a bit, his politics weren't perhaps as dispassionate as those of our own in-house historians, such as the good Doctors Y and Z, who are all of course beyond reproach; and it's all for the public good, anyway. Well, Stalin would have agreed. Oh, yes, and our National Museum of Enviable Objects has just digitized its entire archive, making it accessible to everyone, not just a bow-tied elite; terrific. Just one snag, though: that nice man who paid for the digitization has thrown in a few extra references to slightly dodgy pieces in his own collection; what a shame we can't sort out what's what any longer, now that the original records have gone up in smoke. (Something approaching this happened with archives at the Tate and the V&A, and only the efforts of a few brave, dedicated and stubborn individuals brought it to light.) How convenient if all our classical writers could be tidied up to conform to the prejudices of the day; the good Dr Bowdler made a start, but now his task would be so much easier, and the outcome so much more thorough!

Paper is another matter. It has its enemies, but in the mass it is awkwardly durable. Think of the publications of the early nineteenth-century “Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge”; described by Wikipedia as “Whiggish”, it nonetheless managed to do exactly what it claimed, and spread a lot of valuable information, to the point where it couldn't be recalled and destroyed with a couple of mouse clicks. Every printed book that leaves the warehouse is part of that diffusion of knowledge. Even the ones we (in our superior wisdom) despise can still tell future generations a lot about our own taste and values; and the books that matter, when they are diffused all over the world in a format which resists invisible tampering as few others, will (to paraphrase Hugh Latimer) light such a candle as shall never be put out.

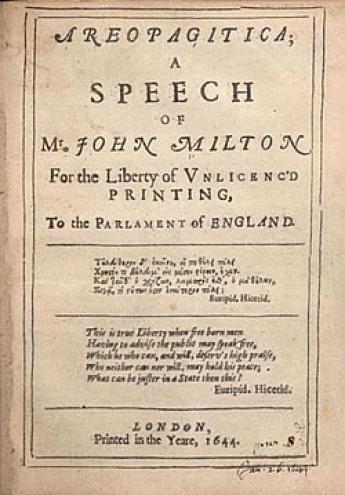

The Internet is a wonderful thing, and we should remember that its detractors are the spiritual heirs of Gutenberg's enemies. But freedom of information can become chargeable, and it can also be taken away: short of circulating our personal versions of Areopagitica, perhaps the most responsible thing we can do is just to carry on diffusing the printed word.

(Published on the website of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association (ABA), presented here by permission of the ABA.)