Antiquarian Booksellers' Association

Patrons of booksellers and how they paid them a century ago

By George Smith

Glancing at an old account book, ranging from 1835 to 1850, with a few entries in 1851, which in some way had come into the possession of my predecessors, I was struck by the occurrence of the names of book-collectors such as Ashburnham, Beaufoy, Beckford, Drury, Phillipps, Spencer, Vernon and numerous others - libraries which have been dispersed in my lifetime. It is concerned only with payments received, and though the sales of single books for cash are recorded they do not often amount to any considerable sum in total. Amongst these items Greek and Latin classics are often prominent with sundry entries which make us envy the unknown purchasers, viz: - Euclidis Elementa Latine. H. Walpole’s copy. 4/- Biblia Latina, folio. Jenson, 1479. £3.10.0 Boccace des Nobles Maleureux, Folio. Red. Mor. A. Verard, 1494. £3.13.6.

Other sales for cash included parts of the Heber auction catalogues, showing that the book auctioneers of London, as well as some on the Continent, were then engaged in the task of disposing of that remarkable time, now nearly sixty years ago, when I had ample opportunity of browsing over a set of these marked catalogues situated on a shelf adjacent to my desk. A greater interest than these cash sales is provided in the amounts paid in the discharge of accounts, although no special books are mentioned, because the names of those paying them are recorded, as is the method of payment, and often they are for substantial sum. Whilst William Beckford, Isaac Disraeli and the Rev. J. Mitford paid in cash, Sir Thomas Phillipps discharged his large obligations by bills, many of them not maturing for over three years; Monsieur Libri adopted a similar practice; a few others sometimes preferred bills also, but the majority of the customers favoured drafts on their bankers, and in most cases the bankers’ names are given; the task of counting the great number of these bankers would be tiresome, but those enumerated most often are first Hoares, followed in order by Coutts, Drummonds and Goslings.

A personal cheque from Mr. Sotheby on Prescotts make one realize how enduring the connection between banker and client sometimes is. Sir Robert Peel’s draft is on the Bank of England, but Lord Palmerston favoured Drummonds as did Henry Reeve of “The Times”, Lord Lindsey, and amongst others, but as might be expected for larger and more frequent amounts - Lord Ashburnham. Equally prominent though as a customer, was the Earl of Gosford who in the earlier years of the volume is known under his courtesy title of Viscount Acheson. His account was kept at Coutts, as were those of The Right Hon. T. Grenville, The Rev. Henry Wellesley, The Earl of Carlisle, Earl Cawdor, Mr. Lockhart and that fearsome terror of Eaton boys, the Rev. Dr. Keate, having in his retirement laid aside the rod ha had wielded so lustily as Headmaster of Eton. Dr. Hawtrey, who followed him at Eton, made his payments on Hoare’s Bank, as did Lord Ellenborough, the Hon. Sidney Herbert, Earl Guilford, Lord Lyttleton, Sir W. Oglander, the Rev. J. Hare, Lord Vernon, the Bishop of Salisbury, and a host of others. The Rev. Dr. Longley, headmaster of Harrow, paid amounts by draft on Hemmersleys of £262 and £223 in the years 1835 and 1836, and in January, 1837, when he had become Bishop of Ripon, £193; he was of course to receive further preferment in the Church and became successively Archbishop of York and Archbishop of Canterbury. Dr. Arnold, Headmaster of Rigby, paid by drafts on Smith Payne, as also did the Rev. Dr. Tait, many years afterwards to succeed Longley as Archbishop of Canterbury.

Very occasionally the receipt of Post Office orders is noted, and in more than one instance from the venerable President of Magdalen, Dr. Routh. Mr. MaCauley’s name occurs as making a small payment, as does that of Mr. Panizzi, then Keeper of Printed Books in the British Museum, but no doubt many of the purchases of the B.M. resulted from his recommendations. Of other institutions the Bodleian, Lincoln’s Inn Library, Sion College, the House of Commons (£750 and £823 in successive years) and Queen’s College whose purchases over several years totalled £3,700, are notable. Of the bookselling fraternity who appear are Bain, Boone, H. J. Bohn, Cadell, Longmans, John Murray, Nattali & Bond, Rodd, Rodwell, Simpkin, Thorpe, &c., &c. Foreign correspondents were Crozat and Techener.

No name of buyers from the USA has sprung to my attention, but it may be of American interest that Granville I. Penn, despite the fact that Pennsylvania Castle, Portland, had passed shortly before from the possession of the legitimate line of the Penns, paid on May 19, 1847, £2,000 by bills at 3 months on Barclays and £1,352 in cash in the ensuing February, showing at all events that he retained some portion of the family wealth.

The titles of the Dukes of Bedford, Buccleuch, Devonshire, Leeds, Newcastle, Somerset and Sutherland, and many marquises, earls and lesser nobles are sprinkled over the pages, accompanied by the Archbishops of Armagh and of Canterbury, and more than a dozen bishops, not to mention deans and archdeacons. Probably my readers will have guessed who the firm of booksellers were who were patronized by so dignified an notable a clientele. There was no indication of this beyond entries here and there of Payne & Foss’s Catalogue 4/- (3/- charged to the Trade). This use of the third person reminded me of Julius Ceasar’s Commentaries and induced me to look at a copy of their catalogue for 1848, where since the number and titles tallied with those of the sales of single books at that date in the MS books, the conclusion could not be resisted that the subject of these lines was a relic of the last years of Payne & Foss, who relinquished business in 1850.

Let us pause for a moment to read how Dr. T. F. Dibdin, so abhorred by the modern bibliographer, refers to this establishment in his “Bibliophobia: Remarks on the Present Languid and Depressed State of Literature and the Book Trade”, published by Henry Bohn in 1832:

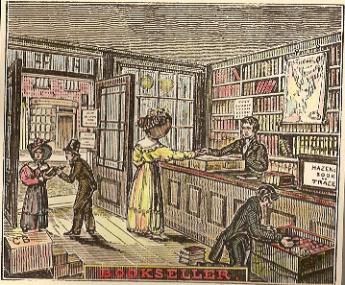

“I steadily paced on to the ‘Castor and Pollux’ of Pall Mall, and there entering a suite of backrooms in which in former times, I was wont to see, assembled some of the more eminent by the ‘literati’ of the day - archbishops, bishops, earls, Doctors in Divinity and Physics, academics renowned in either their University, senators, judges, lawyers, wits, poets and punsters - I gave myself up to profound reverie. Not a mouse was stirring…. Vellums, large papers, uncuts: - Jenson reposing here. Metelin slumbering soundly there. Azzoguidi and Aldus - Giunti and Giolito - Wynkyn de Worde and Wyer - all intertwined in somnolent embrace”. … ‘Where are your expected purchases, gentlemen?’ … ‘Alas, sir. .. All these lovely tomes are likely to become stickers’…

Perhaps booksellers, like the Romans, had had their day. Whenever we see cases of old books arrive from Milan or from Paris we absolutely lack the courage to open them. Not so in former times. The chisel and the hammer then went merrily to work - and ere you could say “Jack Robinson” the lovely book treasures, membranaceous or otherwise, were arranged in inviting order on the floor: within forty eight hours up started a tribe of intending purchasers - and the articles seemed to march off in double quick time as if set in motion by the tap of the drum. How long will it be ere we hear the sound of that tapping again?’”

From what we have already seen, by 1835 the revival in the book trade had come about, even more rapidly that it did after the corresponding slump a century later, again John Payne and his partner Henry Foss were hearing that tapping and welcoming once more the more eminent literati of the day. Quoting Dibdin again we find him stating in the supplement to the 1842 edition of his ‘Bibliomania’ (page 584) that the library of Richard Heber “was consigned to the care and direction of Messrs. Payne and Foss - booksellers of long established eminence and respectability.” So apparently it was they who arranged for its disposal in twelve parts spread over two years, distributing it amongst three book auctioneers, five to Sothebys, five to Evans and two to Wheatleys. No payments are recorded in the M, from these auctioneers in respect of the Heber sales, probably because any commission P. & F. might have been entitled to was swallowed up many times over by their own purchases, and information regarding this might have been stated in a corresponding book of ‘Payments made’, which for all I know may have been preserved somewhere.

John Payne represented the third generation of a famous family of booksellers. Those of the first generation were his grand-uncle Olive Payne, with whom John Nichols (ignoring the catalogues of booksellers in early Stuart times, such as Robert Martin and George Thomason) says the idea and practice of printing catalogues [meaning booksellers as opposed to auction catalogues] originated, and his grandfather Thomas, well known as “Honest Tom” Payne - the benefactor though not a relative of that attractive personality, the bookbinder Roger Payne. Thomas had his shop at Mews Gate, near by the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields; he took his son, also named Thomas, into partnership, and they carried on together for twenty years until 1790, when the father retired. In 1806 the son removed to Pall Mall and seven years later promoted his apprentice Henry Foss to partnership, the firm henceforth taking the style of ‘Payne and Foss’, banteringly transformed by Charles Lamb into ‘Pain and Fuss’. The mention of Charles Lamb brings to mind his friends the Burneys, and Sally Payne, sister of the younger Thomas who married Dr. Charles Burney’s sailor son, Admiral James Burney, whose ‘Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea’ is in its sphere as standard a work as that of his father’s ‘History of Music’. The Admiral’s daughter, also named Sally after his wife, married here cousin John Payne, who took his uncle Thomas’s place in the firm when the latter died in 1831. The manuscript volume provides no clue as to why in 1850 both partners retired and the business came to an end, but perhaps questions of health prevailed and John and Sally Payne, as Robert and Elisabeth Barrett Browning had been, were attracted to the sunny skies of Italy, for they took up their abode at Rome, where it is said they spent the remainder of their lives.

(Published in the ABA Newsletter No. 16, April 1951, posted on the website of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association. Presented here by permission of the ABA).