Actualités Antiquarian Booksellers' Association

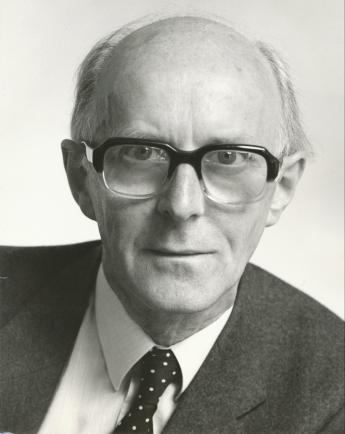

"New Trends in the International Antiquarian Book Trade" - Lecture given at the 30th ILAB Congress in Tokyo 1990 by Anthony Rota

Lecture given at the 30th ILAB Congress in Tokyo 1990 by Anthony Rota

The exact title of my talk this morning is unimportant, for no matter what subject you set an antiquarian bookseller, no matter what he is supposed to be speaking about, he will end up talking about books. It is in his nature: he cannot do otherwise. Nevertheless I do not propose to speak only about books, but also about bookshops and booksellers, the structure of the book trade and the very mechanics of bookselling. I do so in the hope that librarians and book collectors are not without interest in the way in which books reach them, and in the factors which influence the prices that those books command.

Most of what I have to say will necessarily be based on my experience of western books and, to a lesser extent, western markets, for that is where my experience (almost 40 years of it now) lies. Nevertheless the very first point that I want to make is that the bookselling community is now, more than ever before, an international one. Throw a stone into the bookselling pond while standing in New York and the ripples will spread out to Amsterdam. An increase in demand for a particular type of book here in Tokyo will be reflected in prices in the London auction rooms.

The reasons for this increasing interdependence of what used to be very separate geographical markets are really very basic: they are the developments which have made the world so much smaller a place than it seemed to us in 1940 or even in 1950…

Auctions

One trend which I personally do not welcome unreservedly is the growing prominence of the auction houses. Here I speak not so much of the firms which are part retail booksellers and part auctioneers, as is often the practice on the continent of Europe. Rather am l concerned with the multinational corporations whose growing power in the market seems to me to have dangerous implications for the long term health of the bookseller’s trade. The auction houses used to be primarily wholesalers. That is to say that they sold books in quite large lots, and most of their buyers were dealers who would divide the lots up and sell them to their own customers volume by volume.

Now the major auction houses and l speak particularly of Sotheby's and Christie's - employ powerful publicity and public relations machines to woo and court the private buyer. Their publicity campaigns have been so successful that there is now an alarming tendency for all the best libraries and collections to go for auction when the time comes for them to be sold, and fewer and fewer private collections are in consequence offered to the bookshops.

In their defence the auction houses tell us that they have created many new customers for us, and that they have moved prices upwards to everyone’s advantage. That they have found new markets may be good, but my fear is that the new prices run the risk of making book collecting a hobby that only the very rich can afford.

Geographical Movements

In October 1990 nobody in this room will need me to remind them that we live in a time of highly volatile exchange rates. What may not be remembered is that this was not always the case. Changes in the relationship between the pound and the dollar, between the Deutschmark and the yen, did take place of course, but they tended to be more gradual.

Certainly the strength of the dollar through the 1950s and 1960s meant that the trade across the Atlantic was almost entirely from east to west, from Europe to the United States. By the 1980s things changed a little and dealers from Great Britain and continental Europe were able to buy regularly and profitably in North America. Indeed one highly successful bookseller in Washington D.C. tells me that sales to visiting British booksellers now form an important part of his turnover.

Also in the 1980s we saw in increase in the flow of Western books from Europe and America into Japan, influenced no doubt by the relative strength of the yen against the dollar and the European currencies, particularly the pound. Latterly we have also seen the beginning of a keen demand from South Korea.

In addition to these stately flows of material following the long-term strengths of various currencies and economies, I have been amused to note various smaller eddies and flurries. For example if the pound fell five cents against the dollar we could count on an early visit from a certain California bookseller. If the Swiss franc strengthened by 10% a dealer from Geneva would arrive in London the next day. I little thought when I became a bookseller that I should have to pay such close attention to the financial pages of the newspapers!

Loss of City Centre Book Shops

Perhaps the trend which I most deplore is the marked diminution, in the Western world, in the number of traditional second-hand bookshops in city centres, particularly provincial town and city centres. From what I hear and see the situation is healthier here in Japan, but in Europe and North America good, old-fashioned, general second-hand and antiquarian bookshops are becoming quite scarce. Do not misunderstand me: the number of dealers is not diminishing, indeed it is growing; it is the medium-sized firm with a 'walk-in' bookshop which is disappearing. The reason of course is the high cost of operating in city centres. It seems that only airline offices, supermarkets and clothes boutiques can profitably occupy city centre sites today. As a result we have seen and are continuing to see two distinct and opposed movements in the pattern of antiquarian bookselling.

First there is the move towards one-man specialist firms. Such businesses usually operate from apartments in the residential quarter of the city, or from rooms in private houses in the country. I think of this as the 'cottage industry' style of bookselling. The other and contrary trend is for more and more business to pass into the hands of fewer and fewer large and powerful firms. The one-man specialist firms provide a very useful service. Their expertise and the degree of personal attention they give represent a great boon to the book-buying community at large - but there is a drawback. A librarian or book collector visiting a distant city, perhaps in another country, could easily visit its bookselling district, its Charing Cross Road, its Fourth Avenue or its Kanda. A number of shops could be seen in the course of the day. It is much harder to make a tour of the one-man business, some of which are located at remote addresses. Moreover the mere fact of having to telephone to make an appointment, and perhaps having to walk through a man's drawing room to reach the cases where he has his stock, creates an artificial atmosphere between buyer and seller. There is not the same freedom to roam the shelves and to buy or not entirely as one pleases.

Does it really matter? The answer has to be 'yes'. We are losing the base of the pyramid, the street-level, open access shop, where both young dealers and tyro-collectors are trained. Moreover booksellers operating from offices or from home do not enjoy the same buying opportunities as those in conventional shops.

It can be argued that the world's stock of rare books is divided into two parts: those that the world knows about and those that it hasn't discovered yet. The first kind sets us no problem, but the second kind is a cause for concern. Owners who are not themselves collectors of rare books, but who have perhaps inherited a small library from a husband, a father or an uncle, might well approach the bookseller in his familiar shop in their local High Street. Certainly most of us have bought many good books from just such a beginning. The seller I have in mind would be less likely to seek out a dealer in a remote cottage in rural England or rural New England for that matter.

Because the general open-access bookshop is vanishing, the world of rare books is thus losing in three ways: the training ground for assistants; the place for young collectors to cut their teeth, as it were, on relatively inexpensive books; and a chance to buy unsuspected rarities. If this were an ecological talk instead of a bibliographical talk I should be speaking about the danger to the species when the habitat, the feeding-ground, is in peril.

Fashion in First Edition Collecting

Now let me turn for a moment to one of my own firm's specialities, the field of modern first editions, that is to say first editions of English Literature of the last hundred years. I would like to dwell briefly on two up-to-the-minute trends, neither of which I think is wholly healthy. The first is the seeming insistence of collectors on all seeking to collect the same handful of authors. A particular writer suddenly becomes and everyone wants his books. We have seen this happen in the cases of, for example, J.R.R. Tolkien, John Fowles, D.M. Thomas, and Ted Hughes. I could name many more. For months, perhaps even for a year or two, everyone wants books by these authors. Then fashion changes, and prices, which have been lifted artificially high, tend to tumble, often quite dramatically.

This insistence on fashion, which one of my colleagues has wittily dubbed 'flavour-of-the-month' bookselling, has led to the second trend, the trend towards a highly selective market. Thus it is that prices for the so-called 'fashionable' authors have climbed to near-ridiculous heights, while the work of steady, solid, major writers (Arnold Bennett, Somerset Maugham and George Moore are just three examples) hardly sells at all, however cheaply priced.

The next trend I want to speak of is towards insistence on the presence of the dust- jacket. Now the origin of the dust-jacket was as a protection to keep the book itself in fine state until it had been sold. Then it was thought quite proper to discard the jacket and to shelve the book without it. But of course the jacket came to serve various other purposes as time went by. It was a promotional aid, a marketing tool, and in its way a small poster. It often contained bibliographical information both about the volume it covered and other books. Increasingly frequently it bore words of praise by other famous writers.. Increasingly the artwork would be that of a distinguished artist. For all these reasons my firm has always preached that it was worth paying a premium to buy a copy in the dust-jacket as opposed to one that lacked it. Now, however, things seem to me to have gone too far. A new generation of collectors has been constrained never to buy a book without a jacket- and that means that some of them are going to have gaps on their shelves for a very long time. Moreover the price differential between books with and without their dust-jackets has now reached seemingly absurd levels.

Let me give you two examples. In 1982, when ordinary copies of the first edition of H.G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon, without dust-jackets, could be bought for perhaps $60, a copy in the dust-jacket was offered for sale in America for no less than $4,500.

In 1981, when copies of Kenneth Grahame's classic The Wind in the Willows, without jacket, could regularly be bought for £250, a copy in the jacket brought £3,200 at Sotheby's in London.

Prices

Since my task today is to talk about new trends in book-collecting I do not propose to say much about prices, for there is nothing new about their continuing upward movement. A colleague who has been a bookseller in Great Britain for 30 years, tells me that as a rough yardstick and a guide to today's prices, he multiplies by thirty the figures at which books were sold when he first came into the trade. Make the experiment on books with which you yourself are familiar. Quite often I think you will find that even thirty is not a large enough multiplier.

Are high prices good or bad? They sometimes have the virtue of attracting onto the market more copies of particularly rare titles. They certainly have the effect on book-selling firms of causing them to need much more capital; indeed many of the largest and most powerful firms in the market today rely quite heavily on outside money, whether it comes from banks or from private investors. I remember how surprised I was to see the head of a particularly distinguished London firm walking into Sotheby's one morning accompanied by no less a figure than his bank manager! Such a thing would have been unheard of even twenty years ago.

Book Fairs

ln Tokyo this week there is a splendid and exciting example of the very best in Antiquarian Book Fairs. Fairs such as this have, at least in modern times, a fairly short history. Their modern development can be said to have begun in London. Now major fairs are held regularly, some of them with sales comfortably in excess of two and a half million pounds. Smaller fairs proliferate. I do not think there is a weekend when there is not at least one fair somewhere in Great Britain, for example, and I believe they take place in America with equal frequency. 'Whether fairs are 'a good thing' or 'a bad thing' is a subject in itself. I do not propose to discuss it at length now, but would merely point out that the small fairs, (as opposed to the large and carefully regulated fairs sponsored by the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers and its member associations) give those seeking to enter the antiquarian book trade an effective and inexpensive way of doing so. What I regret is that these newcomers, welcome though they may be, do not necessarily serve an apprenticeship in an established firm, and thus acquire the training and experience which I believe to be necessary if they are to serve the public in the best traditions of the trade.

Catalogues

Despite the phenomenon of the Book Fair, the bookseller's catalogue remains a very important way of selling books. It is true that there are booksellers who never issue catalogues at all, but these are a definite and small minority.

I have made no statistical analysis of the number of catalogues that arrive on my desk every week, but I have a very clear impression that the quantity has grown markedly in recent years and is still growing.

Again I have undertaken no research to prove the point, but I am sure that the standard of scholarship in these catalogues has also risen and is continuing to rise. The new generation of dealers seems to make good use of the flood of bibliographies published in recent times. Indeed, if anything they make too much use of them, giving bibliographical citations for commonplace and straightforward books which present no bibliographical problems either to buyer or to seller.

It has always been said that booksellers' catalogues make good reading, whether or not one has any serious intention of buying the books that they list. In some cases that is particularly true where specialists have gathered together an impressive assemblage of books in one particular field and present them with scholarly footnotes which advance our knowledge in that area. I could give many examples but I will choose only one, a fine series of catalogues devoted to books about architecture, issued by Mr Ben Weinreb. These are models of what such things ought to be, and make me proud of my chosen calling.

There is a difference between catalogue footnotes which are genuinely informative and those which merely make gratuitous value-judgments. The former may perhaps cast new light on even the most familiar of books and can add to our knowledge. The latter simply give half-baked, home-spun philosophical reflections on books which need no help of this sort to sell them. I have in mind one dealer who catalogued The Bible with the footnote that although no believer himself, he thought it a great work of literature! Some booksellers in the western world find the easiest way to obtain footnotes is to quote liberally from the Dictionary of National Bibliography. So many dealers now follow this practice indiscriminately that I sometimes suspect that if all the footnotes extracted from the DNB in the course of one year were put together with scissors and paste, the entire thirty-one volumes of that mighty reference work could be reconstructed!

On a happier note I am quite sure that typographical standards in catalogue production are improving dramatically. A number of dealers have employed the very best professional typographers to design house styles for them. Others use computers, and the desk-top publishing programmes that they bring with them, to produce clear print at a reasonable price. The days of barely legible lists, run off in a basement on an aged and badly serviced duplicating machine are surely past us now.

I said that desk-top publishing programmes helped to keep costs down, but printing is not cheap and postage costs are also a considerable factor in the economics of bookselling. These two considerations between them are bringing changes in the pattern of catalogue distribution. In earlier days, while booksellers eagerly sought new names to put onto their mailing list, they hardly ever gave attention to taking names off it. Private collectors might well remain on a list until the time of their death, even if they made scarcely a single purchase. Libraries were probably never removed from mailing lists at all. How all that has changed. Today I know of no dealer who does not regularly prune his mailing list, removing from it automatically those who have not ordered for a specified period of time. Nowadays this weeding-out process applies almost as rigorously to libraries as it does to private collectors.

Equally, more and more booksellers are inviting customers to subscribe to their mailing lists, i.e. to pay for the catalogues they wish to receive. In my own view this is a trend that can only go so far. It is all very well to ask those who seem to collect catalogues rather than books to contribute to the cost of their hobby, but my sympathy is with the customer who said that being asked to pay for booksellers' catalogues was like being asked to pay for the showcases in which the jeweller displayed the rings and brooches which my friend occasionally bought for his wife.

The Pattern of Demand

Just as there have been changes in the geographical pattern of demand over the last several decades, so there have been switches in emphasis in the importance of particular categories of book buyer. The 1950s saw the beginnings of an upsurge in buying by university libraries, particularly in North America. This was partly as a result of what was known as 'the learning explosion', when every eighteen-year-old seemed determined to exercise what he saw as his right to a university education. In consequence small universities became large ones. What had been teachers' training colleges became fully fledged universities. In both instances the institutions thought to demonstrate their new stature by building a library of rare books. This was a period of almost indiscriminate expansion and it came to its peak in the mid-1960s. By then the buying power of American universities was the despair of many private collectors, who felt they were being priced out of the market.

After that apogee various factors began to combine to reverse the swing of the pendulum. First there was the demographic shift. The number of children reaching university-age started to dwindle. This brought about a decrease in the capitation fees paid to universities from central government. Then there was the spirit of anti-elitism that was abroad in the land. Suddenly spending tax dollars on rare books and manuscripts seemed a less worthy thing to do. Furthermore there was disenchantment after the unrest on many United States campuses. At the same time inflation added to universities' budget problems. Rare books had always been regarded as the icing on the cake. When there was not enough money to buy all the cake that was wanted, the icing had to go.

Happily for booksellers, demand from the private sector took up much of the slack. And books that would once have been sold to institutional libraries were bought instead for private collections.

For the bookseller this was a mixed blessing. He had lost his wholesale buyers, who might order fifty or a hundred items from a catalogue, and buy author and subject collections en bloc, and had exchanged them for exacting private buyers, purchasing on a volume by volume basis. The bookseller therefore had to work much harder to produce the same results.

On the other hand there was a hidden bonus. When a book is sold to a university library it has, save in the rarest circumstances, vanished from the market for all time. What a dealer sells to a private collector he has a reasonable hope of buying back again, either from the collector when he changes his interests, or possibly from the collector’s estate in the fullness of time.

Here in Japan in the years just past, there has been a great increase in university buying. The word is that that particular trend has now been reversed. Whether that is so you will know better than I.

We have spoken of changes in the relative importance of different categories of buyer. Now let us look for a moment at the changes in demand for different categories of material.

One phenomenon of the 1950s, directly related to the growth in research libraries in the United States of America, was an upsurge in the interest paid by academics to the manuscripts of 20th century literature, not excluding work by living writers. The best single example, and certainly the most intellectual, was at the University of Texas, where the Chancellor was determined to turn his library into one of the best and most celebrated in the western world. Starting several hundred years after Yale and Harvard, he knew that it was too late to try to match the holdings of those institutions in early books and manuscripts. He therefore decided to concentrate on the papers of 20th century writers (which older institutions had virtually ignored) demonstrating as he did so, how much could be learned about the lives of authors and about the history of publishing from a study of manuscripts and correspondence files. Of course such material also reveals a great deal about the creative process itself.

The activities of the University of Texas, soon followed, albeit to a lesser degree, by many other universities in North America, caused a serious drain of these literary resources from the United Kingdom which, rather belatedly, began to show an interest in the manuscripts of its own contemporary literature. The market forged ahead through the 1960s and 70s, and only began to slow when temporary changes in policy in Texas combined with a restriction on university budgets generally. It think it is fair to say that today manuscripts of major writers still sell very well, but it is hard to find a buyer for some of the minor writers whose papers would have been snapped up very quickly, even ten years back.

The period we have been looking at this morning also saw a swing in demand from the products of men’s imagination (poetry and fiction) to landmarks in science and philosophy. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in the high prices now paid for works listed in the monumental catalogue Printing and the Mind of Man published in 1967. Books as diverse as the first edition of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, Lord Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys, (which had a bearing on the raising of entire generations of children, not just in Britain but across the world), and works on the discovery of electricity and penicillin - all these are now keenly sought out. Their worth is recognised by all where previously it had been left to lone pioneers (such as the late Percy Muir, one of the founders of the ILAB), to point out their virtues and to attempt to draw the interest of collectors and librarians to them.

I sense that there has been a growing awareness and interest in the mechanics of book production, the history of the way in which books are made and have been made since 1455. There has always been keen demand for the first book printed in moveable type, the first book with illustrations, the first book printed in a particular country and so on. Latterly that interest has developed and extended to more recent times and more recent processes. We are at this moment at something of a watershed in the history of printing. The last few years have seen more changes in printing technology than occurred in the whole of the preceding five hundred years. For practical purposes printing from hot metal is now a thing of the past. Thus it is that collectors eagerly seek out such things as the first book printed with the aid of a film-setting process. This is a demand which I expect to continue.

Another new area of collecting is what might be described as “Industrial Archaeology”: early books on street lighting, both by gas and be electricity, for example, or books on the provision of clean water supplies to urban areas. I am told that the buyers for these books are not the traditional book collectors, but an entirely new market, including some of the younger academics at some of the newer universities. Interest in the subject and the development of the new market are both very much to be welcomed.

In my own specialised field of modern English and American literature collectors have become much more sophisticated. It used to be the case that they were content co collect only the first printing of each book by the authors in whim they were interested. Now they build author collections in much greater depth. In the case of English authors, for example, they seek not just the first edition published in England but the first American edition as well. They are anxious to have significant new editions too, and set out to build collections which chart the entire publishing industry of their chosen authors. This is a trend which we can only applaud.

Investment

You may well expect me to say something about investments; certainly that is one of the trends that has occupied some dealers’ minds in recent years. Investment in rare books is not a new phenomenon, but of late it has certainly been on the increase. There are a number of reasons for this. One is that investment analysts and financial advisers noted the acceleration in the rate of increase in book prices. Another is that, in days of high inflation and uncertainty about money values, people have increasingly been seeking to put their savings into objects rather than share certificates, hoping that the objects would rise in price at least as fast as money fell in value.

Is this increase in investment in rare books wholly a good thing? Personally I have reservations. They arise from stories I heard at my father’s knee about the crash in the 1930s. Of course the situation then was vastly different: books had been driven up in price far beyond the levels that were truly supported by their significance and their rarity. Nowadays I believe that prices although high, are more soundly based.

It remains of the first importance for those who would seek to invest in books to get the best possible professional advice. Nor should they look for quick returns. The dealer’s margin on the buying and selling of a book is obviously far greater that the stockbroker’s margin on stocks and shares. It therefore takes longer for prices to increase sufficiently to cover this margin. It is also crucial to choose the right time to sell. That is why the more conservative booksellers would argue that only that part of a customer’s funds which he can afford to have tied up for some time should be put in the book market. Danger comes when too many investment buyers all decide to sell at once.

This having been said, book prices are now at a level where customers need to think seriously about the potential re-sale value of the books they buy. My personal believe is that the best reason for buying a book is because one likes it: if it happens to go up in value then that is a bonus.

I suspect that investment buying will be with us for many years to come, but it is still only a small part of the whole antiquarian book trade and I for one hope that it will remain so.

Conclusion

These then are some of the changes and some of the trends in the antiquarian book trade today. Booksellers, like the collectors and librarians they serve, are conservative creatures. By their very nature they are resistant to change; yet they are caught up in the changes that beset us today, and if they do not welcome them they must at least learn to adapt to them if they are to flourish. The antiquarian book trade has managed to cope with changes over a number of centuries now, and I do not doubt for a moment that it will continue to do so.